|

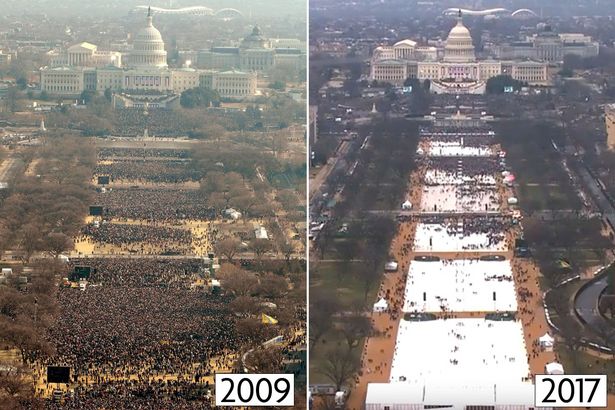

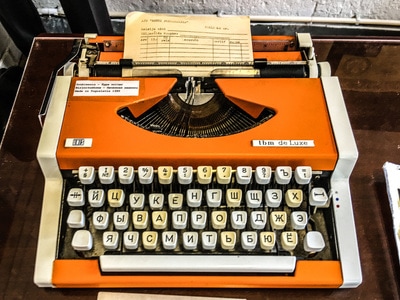

As you’ve no doubt noticed, things have gotten messy lately. And I don’t mean you-need-to-clean-your-room messy, I’m talking about full-scale, five-alarm pandemonium, as if we’d all just learned that the Earth's been dislodged from its orbit and is falling into the sun. Not pleasant, obviously. But extremely energizing. And no one is more energized than comedians and bloggers like me who like to lace posts with a bit of humor. These days, we’re never short of material. To name just one rich resource of public merriment, there’s Kellyanne Conway. One of the most powerful people on the planet — she ran the President’s campaign and is now his closest advisor — she gave us all a chuckle on inauguration day by dressing as Sargent Pepper. Two days later, Conway was asked to explain White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer’s “provable falsehood” inflating attendance at his boss’s inauguration. Conway said Spicer was delivering “alternative facts.” The phrase “alternative facts” was greeted with astonishment and great gusts of laughter by many and instantly became part of our vocabulary. The term is often called “Orwellian,” referring to George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984, in which a totalitarian regime insists the populace use only government-approved language as part of a program to limit freedom of thought. References to Orwell became so prevalent that sales of 1984 shot up 9400% to the top spot on Amazon. Apparently Conway simply couldn't resist giving us another juicy example of “alternative facts” that are easily shown to be lies. She insisted, in three separate interviews over five days, that the Muslim ban was justified by the “Bowling Green Massacre,” an incident that never took place. Residents of Bowling Green, Kentucky walked around snickering about it for days and cheerfully launched cottage industries making “I survived the Bowling Green Massacre” t-shirts and buttons. Naturally, a storm of tweets and memes ensued, letting us all get in on the fun. And the reason we know any of this is because we still have freedom of the press in America. I grew up hearing stories about countries behind the Iron Curtain where the only “news” was Soviet propaganda. You’ll notice there isn't any actual Beatles music in the film, and the “facts” are mostly false and always full of political innuendo. If propagandists went to this much trouble to disseminate misinformation about a band, what bigger whoppers were they telling about the serious stuff? But then, what else would you expect when a totalitarian regime controls the media? Like the Soviets, Spanish dictator Francisco Franco suppressed Beatles’ music because it didn't express conservative values. A Spanish musician once told me with enormous glee about the glorious day he got his hands on a bootleg cassette of a Beatles album. “We spent the entire week rehearsing, and on Saturday night we played all their songs at a dance.” The crowd went wild. Take that, Franco and the Thought Police! Choosing what music we play and speaking the truth are just two of the many rights Americans take for granted. But lately there have been troubling developments. “Democracy depends on a free and independent press, which is why all tyrants try to squelch it,” wrote journalist Bill Moyers. “They use seven techniques that, worryingly, [the President] already employs.”

Sounds more like what you’d expect from the Kremlin than the Oval Office, doesn’t it? Among the many dismaying things about Putin’s intimate role in American politics is his track record of suppressing the press. When it comes to freedom of information, Russia is ranked 148 out of 180 countries tracked by Reporters Without Borders. The USA is currently 41. (Note to self: check our rank in their next report.) While some lawmakers on both sides of the aisle seem uncomfortable with muzzling the media, others praise it. “Better to get your news directly from the President,” says Rep. Lamar Smith, a Texas Republican. “It might be the only way to get the unvarnished truth.” Freedom of the press is one of those things you never fully appreciate until you lose it. I’ve visited Eastern Bloc countries where people lived under totalitarian governments that denied them such basic rights as voicing opinions or singing songs they loved, let alone publishing news stories that revealed a politician’s dishonesty or a government cover-up of uncomfortable truths. With all its many imperfections, the American press remains a vital source of information and dissenting opinion, so essential to a free democracy that it is protected by the US Constitution. When the world gets messy, we need more truth, not less. Our ancestors knew they wouldn’t survive long if they insisted that winter was summer and planted crops in the wrong season. Our parents’ generation was appropriately skeptical of “Your check is in the mail,” and “Of course I’ll respect you in the morning.” Truer than ever is the old joke: "How do you tell when politicians are lying? Their lips are moving." Luckily, we still have what Michael Moore calls "The Army of Comedy," which includes not only Stephen Colbert, Samantha Bee, John Oliver, Melissa McCarthy and Alec Baldwin, but each one of us. Through the power of our own social media, we can circulate compelling political satire that makes us laugh, makes us think, and makes it a lot harder for government officials to get away with unvarnished lies. I invite you to use the buttons at the top left of the screen to share this article on Facebook and Twitter. These buttons may not display on some mobile devices. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY

12 Comments

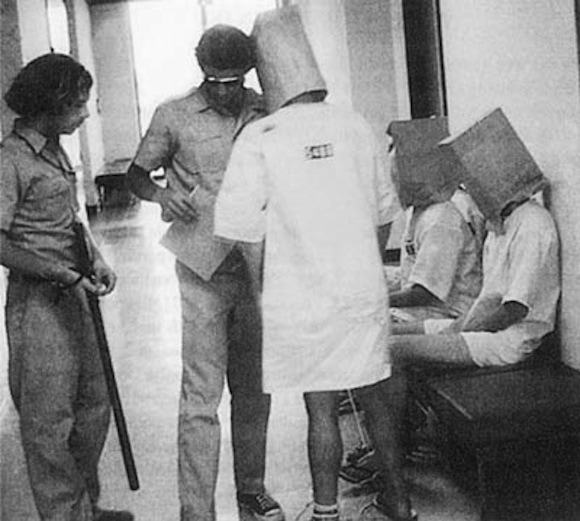

We Americans are famous for finding geographic solutions to all sorts of problems. Trouble at home or college? Road trip! Can’t find a job? Move across the country! Want to add a bit of zing to your retirement? Go abroad! As a travel writer, I love covering (and living) these stories. I was raised on travel tales, the ones older relatives told about my forebears pulling up stakes and heading off into the unknown: my great-great-grandparents crossing the Atlantic in wooden ships, my great-grandparents heading west to California by covered wagon. Itchy feet seem to be in our DNA; by the time I left for college, I’d lived in seven homes in three states. Today, I’m hard pressed to think of an American family that isn’t scattered across half the continent, if not half the globe. The Spanish like to call this having a culoinquieto, literally a restless backside, conjuring images of schoolboys squirming in their chairs, longing to be elsewhere on a fine day. But often we are inspired to seek greener pastures not by a sense of adventure but by harsh economic necessity or the need to flee town one step ahead of people who are interested in killing us. I have no idea of the real circumstances that inspired my Irish, English, and German forebears to brave the dangers of an Atlantic crossing. I suspect the few “facts” that got passed down have been considerably sugar-coated — if not outright fabricated. Did they all arrive with their papers in perfect legal order? I doubt it. But one thing I do know for sure: my ancestors, and those of 98% of all Americans, were immigrants. Every few generations, some descendants of immigrants forget their roots and decide it's time to keep out the latest wave of foreigners seeking a fresh start in the land of freedom and opportunity. Today the line between legal and illegal immigrants has been considerably blurred by new legislation. Although currently blocked, one recent executive order allowed legal residents to be refused re-admittance to the US because of their country of origin and religion. Yikes! That's not suppose to happen in America! Another executive order allows US residents who hold green cards (the ones that make them permanent residents on the way to becoming US citizens) to be deported simply on the strength of an immigration officer alleging that they “pose a risk to public safety”; they don’t even need to be charged with a crime, let alone convicted of one. Where is the due process in that? It's almost as if the government is starting to redefine all immigrants as illegal. Except their own forebears, of course. It’s not easy to be an immigrant these days. But then, it’s always been a rough road, testing the limits of each newcomer's courage, strength, and endurance. Perhaps the struggle itself helped these transplants find the grit and determination to flourish on US soil. Today, 244 million people — 3.3% of the entire human population — have left their motherland to live in another country. Some 41 million of them have found their way to America, and no doubt lots more will do so in the future. And this is good news. Because as it turns out, far from being a drain on the economy, immigrants are good for our bottom line. "Immigrants take our jobs. They don't pay taxes. They're a drain on the economy. They make America less ... American. You've probably heard all these arguments," writes the Atlantic. "Indeed, they've been heard for a century or two, as successive waves of immigrants to this nation of immigrants have first been vilified, then grudgingly tolerated, and ultimately venerated for their contributions. This time, too, there is ample evidence that immigrants are creating businesses and revitalizing the U.S. work force." “Economic analysis finds little support for the view that inflows of foreign labor have reduced jobs or Americans’ wages,” concurs a Penn Wharton report. “The economic effects of immigration are mostly positive for natives and for the overall economy.” Immigrants don't make America less American; they are America. Here are just a few ways immigrants and their families have contributed to the common good. What do we owe to immigrants and their families? Only everything we've accomplished in the last 241 years. And it's no different today. Just ask anybody in the tech industry or California's agricultural Central Valley or the health care industry or New York City where they'd be without foreign-born workers. And now it's payback time. As actor Kevin Spacey puts it, "If you're lucky enough to do well, it's your responsibility to send the elevator back down." YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY  The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania Watching resistance movements growing around the globe, I’ve started thinking of places I’ve visited where oppressed people have won their freedom against seemingly impossible odds. Last year Rich and I traveled through the Baltic States, where much of the last century involved occupation by the Russian Empire, the Nazis, and the Soviets; citizens lived in perpetual lockdown, all rights and freedoms suspended for the duration. “They kept telling us how great everything was,” an Estonian guide said to me. She had the deadpan irony often found in former Soviet citizens, who have a knack for conveying an eye roll and a mental shrug without any perceptible change of tone or expression. “They were schizophrenic times.” So how did the Estonians finally win their freedom? They called it the Singing Revolution. The Soviets had outlawed Estonia’s patriotic songs, but by 1987, with the USSR struggling to hold itself together, people began singing the old tunes at ever-larger public gatherings. As one Estonian said, “If twenty thousand people start to sing one song, then you can’t shut them up, it’s just not possible.” In 1988, nearly 300,000 people — more than a quarter of the population — came together at a festival, waving flags they’d kept hidden for generations. On that day, Estonia’s political leaders began talking seriously and publicly about the road to freedom. Then, on August 23, 1989, two million people— one quarter of the populations of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — joined hands in a 420-mile human chain running from Tallinn, Estonia through Riga, Latvia to Vilnius, Lithuania. The Baltic countries were protesting Soviet occupation, which had recently been revealed as the illegal result of secret protocols in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between the Nazis and Stalin. This revelation provided legal justification for dismantling Soviet authority in the region and inspired two million protestors to take a stand demanding freedom. By 1991 they had it. Never doubt that peaceful protest can be powerful. And as it turns out, you don’t need to muster a quarter of the population to make it happen. It takes just 3.5%, as Erica Chenoweth's research demonstrates. Before doing her research, Erica was convinced “that power flows from the barrel of a gun” and that non-violent protest was, at best, “well-intentioned but dangerously naïve.” Then activist Maria Stephan challenged her to prove it. “So for the next two years,” Erica says, “I collected data on all major nonviolent and violent campaigns for the overthrow of a government or territorial liberation since 1900. The data cover the entire world and include every known campaign that consists of at least a thousand observed participants, which constitutes hundreds of cases. Then I analyzed the data, and the results blew me away. From 1900 to 2006, nonviolent campaigns worldwide were twice as likely to succeed outright as violent insurgencies.” One reason non-violent campaigns work is that they engage people from across the social spectrum: men, women, students, grandmothers, disabled veterans, LGBT activists, knitting collectives, artists, everyone. “No regime loyalists in any country live entirely isolated from the population itself,” Erica notes. “They have friends, they have family, and they have existing relationships that they have to live with in the long term, regardless of whether the leader stays or goes. In the Serbian case, once it became clear that hundreds of thousands of Serbs were descending on Belgrade to demand that Milosevic leave office, policemen ignored the order to shoot on demonstrators. When asked why he did so, one of them said: ‘I knew my kids were in the crowd.’” “Over the last few decades, the world has witnessed the proliferation of a new type of revolution,” writes Daniel Ritter in the Washington Post. “These revolutions largely eschew violent tactics and have become a distinguishing feature of contemporary international politics. Since Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last shah of Iran, was toppled in January 1979 as the result of unrelenting protests and strikes, authoritarian leaders and regimes in the Philippines, Chile, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Indonesia, Serbia, Ukraine, Georgia, Tunisia and Egypt — to mention a few — have met their political ends in similar fashion.” After the dust settles, Erica found, “nonviolent campaigns were far more likely to usher in democratic institutions than violent insurgencies. And countries where people waged nonviolent struggle were 15% less likely to relapse into civil war.” No one can predict the outcome of the rising tide of resistance around the world, any more than Rosa Parks could have foreseen, when she refused to give up her seat in the “colored section” of the bus in 1955, that she would help launch America’s Civil Rights Movement. Students protesting in Prague in 1989 didn’t know that by standing their ground against government troops they would spark the Velvet Revolution, a non-violent transition from communism to a free democracy. “Faith,” said Martin Luther King, Jr., “is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase.” And the only reason we take those first, difficult steps is because we have a pretty good idea what will happen if we don’t. When I was a teenager, a student at a nearby high school asked his history teacher the inevitable question about why good Germans did nothing while the Nazis rose to power. The teacher, Ron Jones, hit on a creative way to demonstrate the answer. His classroom experiment began the next Monday with a description of the role of discipline in fascism. To illustrate his point, he had students adopt more formal postures and manners. The kids loved the game. Jones praised community over individuality and started treating his students like an elite group. They adopted a secret hallway salute that represented a symbolic wave. The response was astonishing. In days, most students were exhibiting blind obedience to Jones and a superior, sometimes hostile attitude toward non-members. Worse, Jones found himself acting more and more like a dictator. On Thursday Jones told the students that the project wasn’t a class exercise but a real-life movement in support of a political candidate. The kids were more enthusiastic than ever. On Friday, they eagerly assembled to meet their new leader. Jones revealed there was no leader and no movement. He explained that in less than a week they’d been duped into acting like fascists. He played a video of Germans marching in disciplined ranks saluting Adolf Hitler. The kids were shocked speechless. Lesson learned. Where were all the good Germans? Just look in the mirror. I’ve always been a bit haunted by that story, knowing that it was only by the sheer luck of school districting boundaries that I wasn’t a member of Jones’s class. Would I have been transformed into a fascist in less than a week? I like to think that I would have been smarter and stronger than that. But I can’t be sure. Jones conducted his experiment at a high school in Stanford University’s hometown of Palo Alto. These were above-average students living an hour south of San Francisco in the spring of 1968, during the full flowering of the resist-authority sixties — and almost no one questioned, protested, or refused to participate. Three years later and a few miles up the road, Stanford psychology professor Philip Zimbardo performed a similar, more notorious experiment. “I was interested in what happens if you put good people in an evil place,” he said. “Does the situation outside of you, the institution, come to control your behavior? Or do the things inside you — your attitude, your values, your morality — allow you to rise above a negative environment?” Twenty-four male students, chosen out of more than seventy applicants as the most psychologically fit, were randomly assigned as prisoners and guards for a two-week stint in a mock jailhouse constructed in the basement of the university’s psychology building. Zimbardo designed the experiment to make the prisoners feel disoriented, depersonalized, and helpless, told the guards not to physically harm anyone, and sat back to see what would happen. I probably don’t need to tell you that events soon spiraled out of control. Those playing guards became increasingly abusive, yelling invective, putting the other boys in hoods and chains and solitary confinement, punishing infractions with sleep deprivation, isolation, and loss of “privileges” such as clothing, mattresses, and use of the toilet. Zimbardo, like Jones, got caught up in his role; he allowed the cruelty to continue, even when some prisoners “went crazy” and had to be released. On day five Zimbardo’s girlfriend, graduate student Christina Maslach, saw what was going on and raised such strenuous objections that the experiment was shut down the next day. More than 50 people had observed the prison conditions, yet Maslach was the only one who questioned its morality. Today the story is taught in psych classes throughout America and is the subject of a recent award-winning (and chilling) film. After Zimbardo’s prison study went public, universities across America rushed to institute ethics regulations that would prevent such experiments from being conducted on students in the future. And rightly so. But we have learned something valuable from this science-project-run-amok: When normal is re-defined, our behavior tends to change with it. This is no surprise. In fact, it's one of the reasons we travel: to place ourselves in new situations that make us think, feel, and act differently. Landscapes of breathtaking beauty can restore our sense of wellbeing. Standing in places where great evil was done raises uncomfortable but vital questions about human nature. Seeing successful social experiments in Estonia and Finland is inspiring. Studying history’s worst failures — Hitler, Stalin, and Vlad the Impaler, to name but a few — reminds us that our collective happiness depends on finding better, more humane ways to treat each other. The world is constantly engaged in social experiments. Can we spot the failures? Will we know when it’s time to speak up and say, “Stop the madness!” as Maslach did? Or will we accept what’s happening, like the 50 good people who watched those boys being abused and did nothing? To find that answer, we first need to ask ourselves this: how is the new normal changing us? |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|