|

When I first moved to Seville, Halloween was not on Spain’s social calendar. Oh sure, everyone had heard of it and seen it in the movies, but celebrating it themselves? That would have felt as alien to them as we’d feel about holding the running of the bulls in New York City. But that was nearly two decades ago, and since then, little by little, Halloween has crept into Seville’s culture. In a way, it’s a natural fit. This city can never resist the chance to party, especially in fancy dress. And everyone here loves a good, blood-curdling ghost story. Tall tales and legends have been passed down for generations — and I suspect get more dramatic with every re-telling. A Spanish friend told me why a long, straight street in Seville’s maze-like shopping district is called Calle Sierpes, meaning “Snake Steet.” The backstory begins during a terrible time the late 15th century when little kids began mysteriously disappearing without a trace. Families were inconsolable, civic leaders baffled. Then Quintana, a young political prisoner in a nearby jail, offered to solve the mystery and reveal the culprit in exchange for his freedom. The authorities agreed. Quintana explained he’d dug a tunnel out of the jail and was making his escape along ancient Roman subterranean passageways when he came upon the villain, surrounded by the bones of many children. Being armed with a dagger, Quintana slew him and fled back to his cell, having decided against a life on the run. When he took authorities to the spot, they found the murderer wasn’t human but a giant snake. They put the serpent’s corpse on display in the street that soon became known as Calle Sierpes. Another famous legend from that era involves Susona, the beautiful young daughter of a wealthy Jewish merchant. She was in love with a young Christian aristocrat, which didn’t sit well with either family; the Spanish Inquisition had just started, and the Christians were carrying out persecutions and pogroms against the Jews. One night, Susona overheard her father and his friends discussing the likelihood of being attacked by the Christians and debating whether they should arm themselves for a preemptive strike on the aristocracy. Fearing for her boyfriend’s life, Susona told him what she’d overheard. That night, a group of Christian knights went into the Jewish quarter, seized the conspirators, and turned them over to the authorities; by dawn, everyone who’d attended the meeting was dead. Horrified, and knowing the community would rightly suspect her of being the informant, Susona ran to her beloved and pleaded with him to marry her right away. "Me? Marry you!? You, who have betrayed your family, your community,” he said. “Do you think I can trust you? No, leave, you will never be my wife." At this point in the story, I always expect Susona to say, “And that’s when I shot him, Your Honor.” Instead she entered a convent. After she died, her head was hung on the wall outside her family’s house, where it stayed for 300 years; a picture of a skull still marks the spot. Everyone started calling that street Calle de La Muerte (Street of Death). Not surprisingly, this had an adverse effect on real estate values, so eventually the street was renamed Calle Susona. I don’t know for sure which convent Susona took refuge in, but it was quite possibly nearby Santa Inés, which has its own ghostly tale. This humble convent was blessed with a magnificent organist, the blind Maestro Peréz. His playing was so spectacular the Archbishop (and crowds of lesser folk) used to come every Christmas Eve to listen. Nearing the end of his life, Peréz still insisted on performing, even when he had to be carried in on a litter. At the age of 76 he expired just as he finished the Christmas Eve service; they found him dead at his keyboard, as he would have wanted. The following year another organist was hired, but of course, he could not compare. The Archbishop went to Christmas Eve mass at the cathedral instead of Santa Inés, and the much-reduced congregation grew restive at the poor performance. And then suddenly, the glorious music they remembered filled the church. Everyone was mystified. Then a woman screamed. People rushed up to the organ loft and saw that the bench was empty, but the organ continued playing. It was a miracle. The Archbishop was furious at having missed it. Half the buildings in Seville have some sort of ghost stories, and that includes the old Hospital of the Five Wounds. No, you didn’t need to have five wounds to go there, the name refers to the wounds of Christ on the cross: hands, feet, side. It was originally built in 1546 to care for sailors returning from the New World with exotic diseases. A century later came the Great Plague of Seville, which claimed a quarter of the city’s population. The hospital admitted 26,700 patients; medicine being what it was in those days (no vaccines, no Paxlovid, etc.) 22,900 of them perished. The hospital closed in 1972, and twenty years later became the seat of the Andalucían Parliament. To this day, people report sightings of the malevolent nun, Sister Ursula, who stalks the corridors looking for her patients. Politicians working in the building say they’ve heard fiendish laughter, hysterical screaming, and agonized wailing, but that could just be parliament in session. Every culture and every generation has its own ghost stories. When my nieces and nephews were younger, I’d spend family vacations at the lake telling them such classics as the man with the hook, the babysitter, and the vanishing hitchhiker. “It was a night just like this one…” I’d begin, watching them lean forward, shivering in delight and apprehension. “Thanks a lot,” my sisters always said afterwards, as they loaded sandy, overexcited kids and damp towels back into the car. “Nobody’s going to sleep tonight.” Sometimes I worried that scaring the living daylights out of these youngsters was wrong, even a form of child abuse. But learning to confront fear is one of the basic building blocks of life. It’s why, in spite of all the worries about sugar overload, unwholesome themes, and fears of fentanyl in the candy, we still celebrate Halloween every October 31st. It’s why Seville will continue to relish the fun of passing on its old legends until the end of time. “All across the world, ghost stories are designed to evoke the same thrill of unease,” wrote journalist Dylan Brethour. “Being afraid isn’t the price we pay for ghost stories, it’s part of the package… We’re animals that are made to be afraid, our survival premised on the awareness of danger. The compensation for that fear is how it also makes us feel alive… In the end, ghost stories are a good way of holding on to something slippery. They give form to our nightmares, both petty and complex, and offer catharsis in return. And that, whether you believe in ghosts or not, makes their stories worth telling.” WELL, THAT WAS FUN. WANT MORE? If you would like to subscribe to my blog and get notices when I publish, just send me an email. I'll take it from there. [email protected] Yes, my so-called automatic signup form is still on the fritz. Thanks for understanding. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY

9 Comments

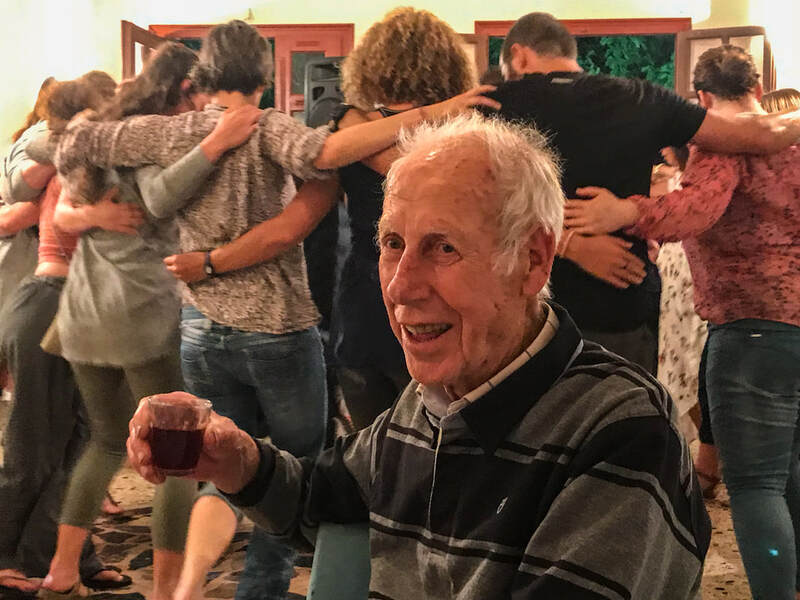

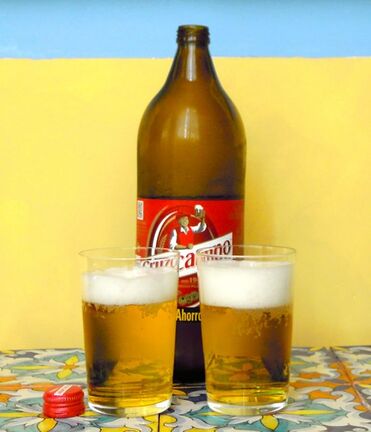

“Look at this island! People there live longer and healthier than just about anywhere. We should go. Maybe it will rub off on us,” I said to Rich a few years ago, while researching our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. “They did a study and 80% of the men between 65 and 100 still enjoy an active sex life.” Impressively, these guys still had plenty of energy leftover to get out on the dance floor as well. The island was Ikaria, Greece, one of the Blue Zones, regions famous for vitality and longevity. I went to an all-night party there, and the 93-year-old who opened the dancing was still at it when Rich and I stumbled out the door in the small hours of the morning. Yowza! There's a famous story about one island resident's powers of recovery. Several people on Ikaria told me the tale, and Dan Beuttner wrote about it in The Blue Zones. During WWII, a young Ikarian named Stamatis Moraitis had an injury that required treatment in the USA. He stayed there, married, and raised a family. At 60 he learned he had lung cancer; his five doctors gave him six to nine months to live. He decided to go back to the island so he could die among his own people; he and his wife moved in with his parents, and Moraitis retired to bed to await the inevitable. Old friends dropped by to share a glass of wine. Occasionally Moraitis would sit in the garden. One day he planted a few vegetables. He started puttering around tidying the vineyard. Pretty soon he was building an addition on the house. “Today,” wrote Buettner, “35 years later, he is 100 years old and cancer-free. He never went through chemotherapy, took drugs, or sought therapy of any sort. All he did was move to Ikaria.” Buettner asked Moraitis if he had any idea how he’d recovered from lung cancer. “It just went away,” he said. “I actually went back to America about ten years after moving here to see if the doctors could explain it to me.” Buettner asked what happened. “My doctors were all dead.” Stories like these are inspiring headlines asking, Should I Retire in a Blue Zone? The short answer is probably not. There are five identified Blue Zones: Sardinia, Italy; Nicoya, Costa Rica; Ikaria, Greece; Okinawa, Japan; and the Seventh Day Adventist community in Loma Linda, California. Although they all enjoy good weather, a laid-back lifestyle, and healthy eating, each has drawbacks. Ikaria, for instance, has no major airport or hospital and is a long ferry ride from anywhere. What the Blue Zone folks have discovered isn’t a fountain of youth, it’s a lifestyle that removes major stressors that make us age faster: time-pressure, isolation, unhealthy food, and the self-fulfilling expectation that at 65 we’ll begin to deteriorate in a variety of embarrassing and debilitating ways. People in the Blue Zones don’t share those habits and attitudes, and maybe it’s time we got rid of them, too. You don’t have to move abroad to do it, although there are places — like Seville — that do make it easier. Personally, I am doing my best to adopt these eight elements of the Blue Zone approach. 1. An active social life. In the US, we tend to live further apart, and everyone’s so busy even dinner with close friends requires planning weeks in advance. On Ikaria, people tend to stroll out most evenings after dinner and drop in on their neighbors for a casual chat. Likewise, in Seville impromptu gatherings are common. New expats join social clubs such as the American Women’s Club and InterNations to find kindred spirits. This is vital, says psych professor William Chopik, because “as we get older, our friends begin to have a bigger impact on our health and well-being, even more so than family.” 2. The Mediterranean Diet. All Blue Zoners follow some version of it, bucking the American fast food trend spreading across the globe. Here in Spain, it’s much easier to eat a natural, plant-based diet. I follow Michael Pollan’s shorthand definition of this approach: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” 3. A little wine every day. A few glasses of wine in the evening is standard on Ikaria. I generally have just one, but I am considering upping my game. Strictly for health purposes, of course. 4. No gym, just natural exercise. I remember years ago dragging myself to brutal fitness classes. Never again. In Blue Zones, daily life includes a lot of walking and other gentle exercise, such as gardening. A large Swedish studied showed gardening and similar forms of puttering around can increase longevity by 30%. Put the money you save on gym fees into tomato seedlings. 5. Daily siestas. People in the Blue Zones tend to rest after lunch. They don’t always sleep; sometimes they read, meditate, or do something equally relaxing. But they hit the pause button and feel better for it. “Don’t think you will be doing less work because you sleep during the day,” said Winston Churchill, who lived to 90. “That’s a foolish notion held by people who have no imaginations. You will be able to accomplish more. You get two days in one — well, at least one and a half.” 6. Sense of purpose. "Everybody needs a passion. That's what keeps life interesting,” said Betty White, who lived and worked to the age of 99. You'll never lack for things to do during a move abroad, but eventually you will settle in and then it's time to develop other interests. Travel is top on my list, with writing and painting in the offseason. Rich has taken online classes on happiness, grumpiness, memory, justice, and astronomy. He arrives at every meal with lots to talk about. 7. No retirement from life. I start worrying whenever I hear recently retired friends say, “I never do anything. I have six Saturdays and a Sunday every week.” Leaving a job can be liberating; becoming a couch potato is less so. George Burns, who lived to 100, agreed. “Retirement at 65 is ridiculous. When I was 65, I still had pimples.” 8. Positive attitude. Blue Zone people don’t fret about aging because they don’t view old age as God’s waiting room but rather as having more time to do things. “Get busy living or get busy dying,” says Morgan Freeman, actor, producer, and political activist. He got his pilot’s license at 65, and at 85 is still having fun doing guest roles on shows like The Kominsky Method. So to recap: No, you probably don’t want to live in one of the Blue Zones. Yes, their lifestyle makes sense, and it’s not a bad idea to see if you can adopt some elements of it wherever you may be. If you're dreaming of living abroad, see how many of these eight elements you’ll find in destinations you’re considering. Maybe someday you’ll be the 93-year-old life of the party on an island somewhere. It’s a tough job but somebody’s got to do it. I'd love to think Rich and I could learn to do this, but to be honest, I couldn't dance like this on my best day at any age. Dietmar & Nellia, you rock!

WELL, THAT WAS FUN. WANT MORE? If you would like to subscribe to my blog and get notices when I publish, just send me an email. I'll take it from there. [email protected] Yes, my so-called automatic signup form is still on the fritz. Thanks for understanding. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY On Saturday, the young waiter at the sidewalk café wanted to practice his English. This is common now in Seville, and at first he did well. Rich and I ordered a platter of scrambled eggs with asparagus, ham, and shrimp that was big enough to share. The waiter nodded, returned with two plates and a bread basket, then said, “You do not need forks, do you? Instantly I pictured myself scooping up handfuls of scrambled egg and stuffing stray asparagus spears into my mouth with my fingers. I stared at him blankly, he repeated the question about the forks, and then added something that I swear sounded like, “For the sex.” Huh? What exactly did he think we were doing with those eggs? Glancing in the bread basket, I saw we already had forks, and pointed this out. He looked mortified and said, “No, no, I am very sorry, I meant knives. You do not need knives.” I agreed we did not. And decided not to press him further on the question of sex. Young people are so easily embarrassed. The really astonishing thing about this conversation was that it was somebody else butchering the language. I’ve been on the other end of countless similar confusions over the years. How well I remember one Spanish class that went like this: Teacher, holding up a flash card: “¿Que hace ella?” (What is she doing?) Me, after a long pause: “¿Cepilla su pollo?” (Brushing her chicken?) Rich, after a longer pause: “¿Camino su pelo?” (Walking her hair?) Whenever I get lost in a welter of linguistic or cultural confusion — and yes, even after all these years, it happens — I pause a moment, recall that day in class, and picture a woman brushing her chicken. It makes me chuckle, if only to myself, and then I’m calm enough to marshal the known facts so I can get a handle on the moment. On Saturday I knew that A) this was a respectable, old-school Spanish eatery, B) nobody in Seville eats scrambled eggs with their fingers, and C) whatever else was about to happen, it was unlikely to involve sex. At least not right there at my café table. Like that conversation with the waiter, I find much of the world feels nonsensical and cattywampus these days. How do we keep from feeling confused and bumfuzzled? The New York Times recently polled its readers about small rituals that help them keep their mental and emotional balance. One woman reads a Nancy Drew book for five minutes before bed. Another sits in a recliner, petting her cat, after dinner. There’s a reader who counts yellow doors, keeping a tally during daily walks. One couple spends a half hour each morning watching birds flutter around the backyard feeder. Everybody had some small daily ritual they considered vital for keeping their sanity. Rich recently revealed he loves doing the dishes after every meal. “I don’t think of anything,” he says. “It’s very relaxing.” Being a supportive wife, I am naturally encouraging him to indulge in this habit frequently. Three times a day, in fact. For his own good, of course. Unfortunately, our routines tend to go out the window when we travel. Rich doesn’t always have a kitchen full of dirty dishes available. It’s not practical to bring your cat everywhere or pack the backyard birdfeeder in your carry-on. We travelers have to get creative about coming up with alternatives. “We’re allowed to make up rituals,” said author Elizabeth Gilbert. “We’re here to find meaning, and meaning is the way we make sense out of chaos. Do whatever you need to do to transition safely from one point in your life to the next.” Of course, there’s a fine line between ritual and superstition. Actress Jennifer Aniston, Duncan James of the boy band Blue, and Kit Harrington, who played Jon Snow in Game of Thrones, all tap the outside of the airplane before getting on board; each has their own specific number of raps, and Aniston always boards right foot first. Hey, whatever gets you through the flight. One of my rituals is well known to my regular readers: the recombobulation coffee. The moment I step off a plane or train, I’m looking for a café where I can sit down, sip something, and regroup. There’s the practical side, such as making sure I have the address of my lodgings and enough local currency to get there. But it’s also a way of reminding myself the headlong rush of getting there is over. Now it’s time to be there; I try to tune into the moment and connect with my new surroundings. I have another small ritual for settling into my room: I immediately place my Kindle and sleep mask next to the bed. I may not need nightly doses of Nancy Drew (although she and I are old and dear friends), but reading before sleep is a deeply ingrained habit. And how’s this for luck? I get to do it twice a day, as my most essential ritual is taking siestas. American friends tend to roll their eyes and suppress a snicker when I say this. But just ask the NASA astronauts, executives wanting to boost productivity, and the longest-living people on the planet about the value of resting each afternoon. It’s a lifesaver, and thankfully it can be done just about anywhere. Whatever our personal rituals, they are vital to our happiness. Why? Scientists and spiritual teachers agree it’s because they offer a sense of predictability in a topsy-turvy world. They let us know we are exactly where we need to be, doing just what we need to be doing, at precisely that moment. We come away more grounded, relaxed, and confident, able to see things more clearly, from a broader perspective. Harvard research shows that rituals alleviate the natural grief that comes with loss, including homesickness and the head-spinning, out-of-control, what-happened-to-my-reality sensations we sometimes experience in foreign places. Especially while having surreal conversations with strangers about eggs, forks, sex, and brushing chickens. Taking time to identify our own rituals, or create new ones to take with us on the road, can help us relax and reconnect with the sense of joy and adventure that caused us to travel in the first place. WELL, THAT WAS FUN. WANT MORE? If you would like to subscribe to my blog and get notices when I publish, just send me an email. I'll take it from there. [email protected] Yes, my so-called automatic signup form is still on the fritz. Thanks for understanding. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY Can you spot the real Vermeer?If not, don’t worry, because neither could the National Gallery of Art in Washington — from the time it was donated in 1942 until last week. New tests revealed Vermeer didn't paint the one on the right, which I call “Girl with an Even Goofier Hat,” although the museum displayed it as “Girl with a Flute.” As if anyone was going to pay attention to the flute with that striped headgear staring them in the eye. The National Gallery of Art is busy wiping the egg off their faces and consoling themselves that at least they didn’t pay a cent for the painting. Not all their colleagues have been so fortunate. Master forger Hans van Meegeren alone sold “Vermeers” to seven other museums for a total of $20 million. As for the highly respected Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, 40% of the works in their collection are fakes, according to its former director Thomas Hoving.  After World War II, Dutch forger Hans van Meegeren was accused of selling national treasures to the Nazis. Figuring forgery was a lesser sentence than treason, he revealed they were fakes. They were so good, nobody believed him until he painted, in front of their eyes, this work in perfect imitation of Vermeer's style. I’m always shocked by such revelations. My mother brought me up to revere museums as temples of civilization’s achievements. In college, my art history professors taught me to respect art for revealing unsuspected truths about our culture and ourselves. It’s demoralizing to know so many museums I’ve loved are filled with knock-offs and pirated goods, like the lair of a successful con artist. Staff member Xiao Yuan said he spotted fakes on the first day of his job as chief librarian at the Guangzhou China Academy of Fine Arts. After a while, he decided to get in on the action. Over time, he made 143 copies, leaving them in place of originals he auctioned off for $3.5 million. Then he discovered he wasn’t the only one getting up to such hijinks. “I realized someone else had replaced my paintings with their own because I could clearly discern that their works were terribly bad.” At least Yuan still had some aesthetic standards. And what about Jackson Pollock’s paint drips or Mark Rothko’s fuzzy rectangles? A math professor in Queens created such convincing “new” works by these and other modern artists that New York’s venerable Knoedler Gallery bought them for twenty years — and sold them for enormous profit. There’s still hot debate about the legal outcome of the $80 million scandal, as told in the film, Made You Look: A True Story of Fake Art. OK, I agree it’s hard to work up sympathy for billionaires bilked by greedy art dealers. But what about nations whose historic treasures have been looted? Most famously there are the Elgin Marbles, hacked off the Parthenon in the nineteenth century, sold to the British government, then donated to the British Museum. Lord Elgin claimed he’d obtained permission from their legal owner, the Ottoman Empire, but the documentation is dubious, an English translation of an Italian transcription of the lost original. The Greeks want their sculptures back, but the prevailing attitude has been, “Finders keepers.” “We can’t even think about returning the Elgin Marbles to Athens until the Greeks start caring for what they already have,” said archaeologist Dorothy King, author of The Elgin Marbles. “If you knew a woman was abusing her child, you wouldn’t let her adopt another. And that’s what the Greeks are asking for.” What? No, it’s not! In that scenario, the Greeks are the mother demanding the return of her kidnapped child. The Greeks kept the sculptures safe for 2000 years, the Venetians blew them up, and the British damaged them with wire cleaning brushes. Who's the fit custodian? Rumors abound that the Elgin Marbles will someday be “shared” with Greece. I’m not holding my breath. You can’t actually call it looting, but Seville’s Museo de Bellas Artes (Fine Arts Museum) is likewise filled with ancient works of art removed by force from their original home. During the nineteenth century, Spain’s government decided to redistribute some of the wealth of the Catholic Church by closing down convents and monasteries and seizing their possessions, including art and real estate. Priceless paintings and sculptures went to museums or were sold to enrich government coffers. Among the seized real estate was the 17th century Convent of La Merced Calzada, now home to the Museo de Bellas Artes, which I visited this week. The room marked Colección permanente houses some wonderful medieval works, and from there the galleries continue chronologically through the Renaissance and pieces by such Spanish grand masters as Velázquez, Goya, Murillo, and Zurbarán. But for me the exhibits really come alive in rooms XII, XIII, and XIV, which house more modern paintings that certainly never graced the walls of religious institutions. This is where my Spanish teacher took me so I could witness Andalusian life in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Las Cigarreras (The Cigar-makers, 1915) is one of my favorites. When tobacco began arriving from the New World, Seville built a huge factory and hired women for their agile fingers and lower wages. It became one of the first places women could work at a paying job outside the home (or the streets). Women brought their nursing babies, inspiring artist Bilbao Martínez to give the central figure a Madonna-like pose. Bullfighters rarely die in the ring itself. In Muerte del Maestro (Death of the Master, 1913), artist José Villegas Cordero shows Bocanegra on his deathbed after being tossed and gored in Seville’s bullring in 1880. Before air-conditioning rendered the steamy Andalucian summer nights more bearable, people used to go sleep by the river, with the night watchman in attendance. The Romani people have been part of Seville’s culture for as long as anyone can remember, introducing flamenco to Europe and inspiring the colorful dress worn in Seville’s annual Feria de Abril (April Fair). I can’t swear there isn’t a single fake in the Museo de Bellas Artes, although if I were a forger, I’d certainly stick with more marketable, lucrative artists like Pollock and Rothko. Spain considers this museum second only to the Prado in importance, but you don’t really come here for celebrity artists, you ramble about enjoying intimate glimpses of the past. “Don’t go to a museum with a destination,” advised New York art critic Jerry Saltz. “Museums are wormholes to other worlds. They are ecstasy machines. Follow your eyes to wherever they lead you, stop, get very quiet, and the world should begin to change for you.” WELL, THAT WAS FUN. WANT MORE? If you would like to subscribe to my blog and get notices when I publish, just send me an email. I'll take it from there. [email protected] Yes, my so-called automatic signup form is still on the fritz. Thanks for understanding. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY “My trip back to Spain? Oh, yeah, it was fine.” That’s what I tell everyone. And it’s mostly true. But every time I say it, there’s a mini movie montage playing in my mind. The Lyft driver who was late picking us up for the airport shuttle. My kind neighbor who offered to drop everything and drive us. Arriving at the San Francisco airport to learn the Heathrow-Málaga tickets, which were absolutely booked and confirmed, had somehow not gone through. Overcoming ridiculous roadblocks to fix that. Rich taking his onboard sleeping pill too early and having a truly bizarre conversation with me over a meal he doesn’t even remember eating. Both of us stumbling off the plane like zombies. The truth is, the trip didn’t start feeling fine until I stepped onto Spanish soil (OK, airport asphalt) in Málaga, where we were spending the night before returning to Seville by train. Within an hour of landing Rich and I were sitting in a tapas bar enjoying ice-cold beer and a plate of jamón (ham), Spain’s most beloved comfort food. Despite my jet lag, I actually managed to get to sleep at a reasonable hour. Then I was jolted awake at 2:00 in the morning by raised voices in the street, followed by a marching band. I stumbled out of bed and pulled open the shutters just in time to see the Blessed Virgin being carried through the streets. Why she wanted to go out at that hour is anybody’s guess, but half of Málaga had turned out to cheer her on. “It’s official,” Rich said. “We’re back.” Perhaps the strangest thing was arriving in Seville after six months away and finding the city and my apartment just as I’d left them. My time in America had been vivid, filled with many adventures, quality time with family and friends, and two bouts of Covid. No doubt it all had changed me in ways I barely understood yet. And while I knew it was illogical, I found it hard to believe the physical landscape had not rearranged itself to a similar degree. The city was just the same as always … or was it? “Why do you go away?” asked sci-fi author Terry Pratchett. “So that you can come back. So that you can see the place you came from with new eyes and extra colors.” I’ve been back just over a week, and I keep walking through familiar streets, eating my favorite tapas in my customary cafés, and marveling as if it were my first time here. Everything seems to have extra colors. “We’re surrounded by the wonders of what we love so much," said travel guru Rick Steves about his joy at being on the road again. "And it just makes our endorphins do little flip-flops." That heady endorphin rush of seeing a well-known place with fresh eyes is one of the greatest gifts travel offers. Many of us have felt it at one time or another. But few — only about 600 in all — have felt the profound euphoria that comes with looking at our home planet from afar. Mae Jemison, the first African-American woman in space, grew up in a world where she often got the message she didn’t belong, didn’t count. “Once I got into space, I was feeling very comfortable in the universe,” she said. “I felt like I had a right to be anywhere in this universe, that I belonged here as much as any speck of stardust, any comet, any planet.” After his 1971 moonwalk, Edgar Mitchell described looking at Earth as an "explosion of awareness" and an "overwhelming sense of oneness and connectedness... accompanied by an ecstasy... an epiphany." Lots of astronauts have reported a staggering, sublime shift in consciousness after seeing the Earth floating in space. They call it the Overview Effect, and it can be lifechanging. “You develop an instant global consciousness,” Mitchell said, “a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it. From out there on the moon, international politics look so petty. You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out and say, ‘Look at that, you son of a bitch.’”  “It didn’t take long for the moon to become boring. It was like dirty beach sand,” said astronaut Bill Anders, who snapped this shot on impulse in 1968.“Then we suddenly saw this object called Earth. It was the only color in the universe.” This iconic photo helped launch the environmental movement. Some people feel the Overview Effect just looking at it. Two years after returning to Earth, Mitchell co-founded the Institute of Noetic Sciences, which researches the link between science and consciousness and gives a biennial award for creative altruism. Not every traveler, or even every astronaut, has an epiphany that inspires them to devote their lives to doing good in the world. But sharing time, conversation, and laughter with people from other cultures, even if it’s just during a tour or a meal, can send us home with greater feeling of connection to all humankind. We may find we have a greater sense of empathy and compassion toward all our fellow sojourners on this planet's journey through space. I’m so disappointed. I keep pressing the space bar on my keyboard, but I’m still on Earth. “I think travel is a powerful force for peace and stability on this planet,” said Rick Steves. “We would be at a great loss if we stopped traveling, and the world would become a more dangerous place … What you want to do is bring home the most beautiful souvenir, and that’s a broader perspective and a better understanding of our place on the planet.” Travel makes us fall in love with the world. With luck it lets us feel the Overview Effect and fills us with so much wonder that our endorphins start doing flip-flops all over the place. That’s how I’m feeling right now, being back in the city I love most in the world, and having the pleasure of rediscovering it all over again. WELL, THAT WAS FUN. WANT MORE? If you would like to subscribe to my blog and get notices when I publish, just send me an email. I'll take it from there. [email protected] Yes, my so-called automatic signup form is still on the fritz. Thanks for understanding. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|