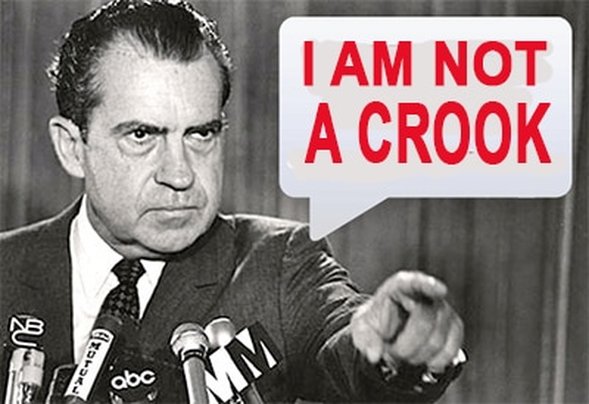

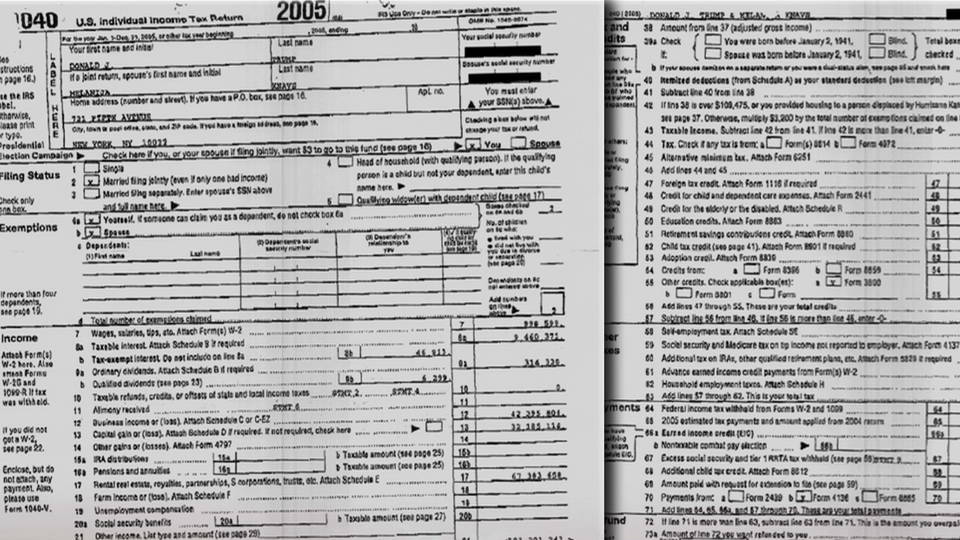

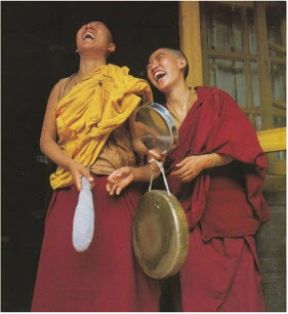

An old Buddhist joke says, “Wherever you go, there you are. Your luggage is another matter.” Most Buddhists I’ve met, especially the holy men known as Rinpoches and Lamas, have an impish sense of humor. A Rinpoche I visited in Nepal asked one of my companions, “Who are you?” My friend gave his name, home state, and profession. “No, I mean who are you?” My friend floundered through a few more biographical details, but that clearly wasn’t what the Rinpoche was after. Eventually my friend sputtered to a halt and said, “I’m so confused.” The Rinpoche roared with laughter. “Good!” he said. “Now we are getting somewhere!” No doubt Buddhist monks take great delight in the confusion they cause every time they spend days creating one of their elaborate sand mandalas and then promptly destroy it. As an artist, this practice made me nuts when I first heard about it. But now I love the in-your-face reminder of impermanence. Some say the monks’ blessings and prayers infuse the sand with a kind of grace. After the mandala is dissolved, the monks pour the sand into the nearest body of flowing water, which carries that grace to the ocean, to every shore, and to each one of us. The world could use some extra grace right now, and I hope the monks are producing and destroying a record number of sand mandalas. But as so many — from the ancient Greeks to Ben Franklin — have said, “God helps those who help themselves.” Working for the common good is a job for everyone, not just Buddhist monks. For me, right now, that means doing what I can to protect my country. It’s a big job, but like the monks constructing a sand mandala, I only have to worry about one little patch at a time. And the patch I’m working on now has to do with the President’s refusal to reveal his tax returns. We can thank Richard Nixon’s financial shenanigans for making presidential tax returns a public issue. Until 1969, presidents received whopping tax deductions for donating their papers to certain archives. As Congress prepared to eliminate that provision in the tax code, Nixon donated his papers and claimed a $500,000 deduction; his 1970 tax payment was just $792.81. When the story broke, Nixon said, “I welcome this kind of examination, because people have got to know whether or not their president is a crook. Well, I am not a crook.” Eventually the country learned that Nixon didn’t officially sign over the papers until nine months after the tax code changed. Tricky Dick had bilked the nation of $500,000 he owed in taxes. Nobody wants to be branded the next Nixon. Gerald Ford, the vice president who took over when Nixon resigned to avoid impeachment, released a tax summary. Since then, every president has revealed his tax returns — until now. The current president’s refusal to share tax information leaves us all in the dark about the extent of his conflicts of interest, his foreign entanglements, and whether he even pays any taxes at all. During a debate, Hillary Clinton pointed out that the only Trump tax returns anyone had seen “were a couple of years when he had to turn them over to state authorities when he was trying to get a casino license. And they showed he didn’t pay any federal income tax.” Trump interrupted her to say, “That makes me smart.” Really? Does that mean the rest of us, who pay the taxes that finance our nation, are a bunch of dummies? If a billionaire president doesn’t feel any moral obligation to contribute towards our roads, schools, police, firefighters, Medicare, military, and the White House itself, why should the rest of us? It makes me wonder just how “smart” he’s been. Nixon smart? I think we have a right to know. And I’m not alone. More than 130 American cities are planning marches on Tax Day, April 15 to demand the president release his tax information. In Seville, Tax Day falls during Semana Santa (Holy Week), when a million visitors flood city streets to watch processions day and night; any protest we’d stage would get lost in the general chaos. What to do? Two weeks ago I was wrestling with this problem and had one of my rare nights of serious insomnia. And somewhere around four in the morning, it came to me: we’d create a Virtual Tax March on social media. People would post pictures of themselves with a protest sign saying to the President, in the immortal words of Jerry McGuire, “Show me the money!” My group, American Resistance Sevilla, loved the idea. We’ve just started posting photos on Facebook; see more at #VirtualTaxMarch on Twitter and Instagram. We’re spreading the word to protest groups around the world, and everyone seems to be excited about jumping in. Want to join in the fun? Here’s how. I don’t know what effect, if any, the Virtual Tax March will have on the president, our elected officials, or the friends, family, and strangers who choose to take a stand with us. Like the monks pouring sacred sand into the river, all I can do is release my idea into the world and let karma take it from there. Several people have written lately to ask if it's OK to share my posts on social media. Yes, absolutely! In fact, I've added buttons at the upper left to make this easier. Share away. For the next two weeks, Rich and I will be traveling through Spain and France meeting up with American Resistance groups. So I won't be posting next week, but I will be back after that with fresh news from the European front. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY

9 Comments

When I was a child, the Wizard of Oz played on TV every Easter, and I'd gather with my whole family to watch it. The opening scenes, set in Kansas, are filmed in black and white. Then a tornado sends Dorothy’s house flying, and after it lands there’s this spectacular moment when she opens the door and discovers herself in the brilliant Technicolor world of Oz. That moment inspired my lifetime of wanderlust. Arriving in a strange land often gives me that same feeling of jaw-dropping surprise and heart-lifting joy. No matter how many times I’ve stepped off a train into an unknown city, I always feel as if I’m stepping onto that yellow brick road in giddy anticipation of astonishing adventures just ahead. Lots of people prefer more predictable travel, like a week on a beach, and that's a great option when we need to rejuvenate. But sometimes we run the risk of outsourcing our entire travel experience. “I pay top price and expect the best,” an American once told me. “I want to be certain that someone has gone before me every step of the way to make absolutely sure that I’m seeing the best views, eating the best food, and staying at the best hotels.” To me, that sounds like a second-hand vacation. It was the guide who had all the fun of exploring the route, meeting locals, and discovering new ways to engage with the world. Spending unscripted time with people from a different culture teaches us a lot — including how much we don’t know about each other, how much interesting stuff has been going on, and how completely oblivious we’ve been about it. “That’s the glory of foreign travel, as far as I am concerned,” says travel author Bill Bryson. “I can't think of anything that excites a greater sense of childlike wonder than to be in a country where you are ignorant of almost everything.” As American travel writer and TV host Rick Steves puts it, “The great value of travel is the opportunity it offers you to pry open your hometown blinders and broaden your perspective. And when we implement that world view as citizens of our great nation, we make travel a political act.” In Ten Tips for Traveling as a Political Act he suggests, “Get out of your comfort zone . . . Travel with a goal of good stewardship and a responsibility to be an ambassador to, and for, the entire planet. Think of yourself as a modern-day equivalent of the medieval jester: sent out by the king to learn what's going on outside the walls, then coming home to speak truth to power (even if annoying).” As a travel writer, I take my role as a modern jester very seriously. I make every effort to entertain and inform, and above all to speak the truth about the many extraordinary countries (including my own) that I explore. Most of the time I have the pleasure of reporting on amusing things that happen in quirky and delightful settings. Occasionally I venture into darker places, such as Auschwitz or old Soviet prisons, and then I give my readers an honest report of what I am seeing, how I’m feeling, and why it matters, with enough context to help us all try to make sense of a world that includes such evil. Humor can help illuminate the shadows of history. A man in Riga, Latvia, told me about the Corner House, the infamous basement (now a museum) in which the KGB conducted interrogations during the era of mass deportations. “People used to joke, ‘The Corner House has the best view in Riga; from there you can see Siberia.’” We are all living in times of enormous societal and political upheaval now. And to me, ignoring that new reality when I’m writing about the world would be like describing the lovely carving on the Titanic’s main staircase without mentioning that it is now underwater and about to take a nosedive to the bottom of the sea. The truth can be uncomfortable, and as Steves points out, some find it annoying. Last week, a reader wrote me: “It would be best to leave three common topics that cause emotional distress for many readers out of your blog. That would be political opinions, religion and sex. Otherwise I really enjoy your blogs Karen. Happy travel writing!” Really? She wants me to write about travel without mentioning politics, religion, or sex? What fun is that? I sat there for a moment trying to imagine how I would describe Rome without a single reference to the Catholic Church, Mussolini, or Sophia Loren. That would be like blogging about Oz and leaving out the flying monkeys and the Wicked Witch of the West, or discussing the movie Poltergeist without referencing the afterlife. “Make a broader perspective your favorite souvenir,” advises Rick Steves. “Back home, be evangelical about your newly expanded global viewpoint. Travel shapes who you are. Weave favorite strands of other cultures into the tapestry of your own life. Live your life as if it shapes the world and the future — because it does.” And if you’ll forgive me for mentioning religion again, I say amen to that. Several people have written lately to ask if it's OK to share my posts on social media. Yes, absolutely! In fact, I've added buttons at the upper left to make this easier. Share away. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY  საქართველოს რესპუბლიკის (Republic of Georgia) საქართველოს რესპუბლიკის (Republic of Georgia) “დილა და როგორ გრძნობ თავს?” inquired our host, when Rich and I stumbled out of bed and down the stairs. We were in a farmhouse in the Republic of Georgia on the morning after a very long night involving wine, food, wine, dancing, wine, and more wine. Even if our host had been speaking English, I’m sure it would have sounded like “დილა და როგორ გრძნობ თავს?” to my befuddled ears. Assuming he was asking how we were feeling, I managed a sickly smile. Our “translator” used dramatic gestures and his eight words of English to convey that we’d feel much better after the traditional Georgian pick-me-up breakfast. This, I was aghast to discover, involved bowls of garlicy broth overflowing with entrails and various unspeakable animal parts. Cooked, thank heavens, but still . . . Luckily the grandfather was entitled to the choicest bits, so his was the portion with the whole cow’s hoof. When asked if I would like a glass of vodka with breakfast, I said “დიახ!” (Yes!”). These warmly hospitable Georgians were clients of ours in the 1990s, when Rich and I undertook a couple of three-month volunteer assignments to help develop much-needed strategies for revitalizing deteriorating hospitals and clinics. The transition from socialized medicine to private pay had turned out to be (surprise!) complicated. In those post-Soviet years, civil war, massive corruption, and economic crisis had left the infrastructure hanging by a frayed thread. Once-fine hospitals had no heat, food, or medicine; patients’ families provided all meals, blankets, and drugs — mostly outdated, black-market pharmaceuticals sold in booths near the hospital. I went there to buy capsules for a cold, but my clients advised instead a folk remedy made from quince fruit; it cured me in 24 hours. Home remedies come in all forms and degrees of efficacy, but when you’re seriously ill or injured, let’s face it, you want modern doctors and reliable pharmaceuticals. Which is why it’s so dismaying to learn that if the American Health Care Act (aka “Republicare”) manages to pass this month, next year 14 million Americans will be without healthcare coverage, and by 2026 that number will increase to 24 million. Ouch! “I don’t know how you could live, knowing that a single serious illness or injury could cost you everything you own,” a Spanish friend said to me. “I would be terrified.” Many of us are. The Affordable Care Act is far from perfect, but it’s a first step toward providing American citizens with health coverage that every other developed nation already considers a basic right of citizenship, like paved roads and police protection. This week the White House, seeking to drum up support for its new plan by throwing Obamacare even further under the bus, sent this email to millions of Americans: So I decided to tell the White House my Obamacare story. I wrote that I love the Affordable Care Act because it provided low-cost coverage for my brother Steve — a working man, a fine musician, and one of the kindest, funniest people I ever knew — during the final phases of his terminal cancer. No one in the family had to sell their house or take a second job to cover his six-figure medical bills. I know, that’s not a very dramatic story. But living through it really taught me what’s at stake. All UN member countries have agreed to try to achieve universal health coverage by the year 2030. If Republicare passes, the USA will once again be the only one of Earth’s thirty-three developed nations without it. At the heart of the proposed bill are flat tax credits that would leave most people — to use comedian John Oliver’s metaphor — as horrifically under-covered as a middle-aged man in an ill-fitting thong. (And no, I am NOT going to share his favorite graphic for this; you’ll just have to use your imagination.) The only clear winners in the plan are the wealthiest Americans, who would see tax breaks of between $33,000 and $197,000. I’m sure we all find it comforting to know that under this plan at least something in America would be healthier: the wallets of billionaires. I doubt that the White House is going to read or appreciate my response to their request for Obamacare disaster stories. But writing it made me pause and reflect on whether healthcare is a right or a privilege. Should medical treatment be reserved for those who can pay for it — a sort of Darwinian, survival-of-the-economic-fittest? I saw what happened in the Republic of Georgia in the 1990s; money allocated to hospitals wound up in the pockets of the rich and powerful, and bribing a doctor to ensure better treatment was routine. Is that what America is becoming? Or do we define healthcare as part of the community’s social contract, like roads, firefighters, and schools? The UN and thirty-two of the world's thirty-three developed nations say one thing; the new Republican plan says another. If Republicare is put into effect, that truly would be a healthcare disaster story. Several people have written lately to ask if it's OK to share my posts on social media. Yes, absolutely! In fact, I've added buttons at the upper left to make this easier. Share away. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY “You can’t really understand foreigners until you are one,” Rich remarked to me today. Instantly my mind was flooded with memories from more than a dozen years ago when we were new residents of Spain. Like most transplants, we worked like dogs (or perros as I had to remember to call them) to come to grips with our new language. Our classmates were twentysomething Europeans who already spoke five languages and found Spanish almost laughably easy to absorb. We, on the other hand, had the unwelcome experience of feeling like complete and utter dunces (bobos) in scenes like this: Teacher, holding up a flash card: “¿Que hace ella?” (What is she doing?) Me, after a long pause: “¿Cepilla su pollo?” (Brushing her chicken?) Rich, after a longer pause: “¿Camino su pelo?” (Walking her hair?)  Does my hair look too serious? Does my hair look too serious? Being a foreigner is incredibly hard work, and there are countless cultural tripwires. Women in my painting class held an intervention about my hair, which they felt should be “happier,” and they let me know my painting (simple, representational stuff) was “too creative.” At first I was offended by these remarks, but then I realized that they were cluing me in about survival in a more conformist society. If I wanted to belong, I should have massive, frilly hair with blonde highlights and paint conventional copies of approved prints of second-rate impressionist works. I was striving mightily to integrate into Spanish society, and I was very fond of these women, but even for them I could not embrace big hair and bad art. So I can tell you from personal experience that for foreigners, it's a tricky business balancing the desire to fit in with the need to be true to yourself. And it’s easy to criticize the results if you’ve never tried to do it. In response to my recent post, Do Immigrants Make America Less American? someone wrote this on my Facebook page (using this spelling and punctuation): People youst to come here to beee. Americans. Now to many come here just for financial gains. Its whats in your heart that makes an american. People need to assimilate. To our. Culture. Not vice versa Actually, if you look at the historical record, financial gain is the number one reason most people originally came to our shores. From the beginning, “the drive to colonize the Americas was almost entirely economic,” says Reference.com. To bolster productivity, between 1501 and 1866 more than 300,000 African men, women, and children were kidnapped and forced into slavery in the New World. The second major wave of Europeans arrived between 1815 and 1865, and while some were seeking religious freedom, most were motivated by economic necessity, including millions impoverished by the Great Irish Potato Famine. Want to know why people come to America? Follow the money. And is it really “whats in your heart that makes an american”? I grew up in a nation that cherished personal freedom, social responsibility, respect for the law, generosity to the less fortunate, and the right to practice whatever faith you chose. And yet we’re now a nation where hate crimes are on the rise — up by double digits in seven major cities. The FBI reports hate crimes against Muslim-Americans have jumped 67% in the past year. Comparing this winter to last, New York City’s anti-Semitic hate crimes have increased 189%. Last week I wrote about people who burst into an 8-year-old’s birthday party to shout racial death threats at that little girl and her friends and family. Should we view the perpetrators of such crimes as un-American? Do we re-define what it means to be American? Or is it time to take steps to stop the madness?  Stalin gets in touch with his inner gaiety in a propaganda poster. Stalin gets in touch with his inner gaiety in a propaganda poster. Understanding our own homeland — let alone other people’s — isn’t always easy. I just learned that Joseph Stalin once said, “Gaiety is among the most outstanding features of the Soviet Union.” Wow, I didn’t see that coming! And here’s another shocker: contrary to what many in the USA believe, most people around the world love their birthplace and don’t have the slightest desire to become Americans — or even to become more like Americans. They have their own views on everything from gun laws to religious freedom to race relations, and they certainly aren’t looking to America for moral guidance. Living in a foreign country, you are a minority in a community where everybody is operating from a belief system you know almost nothing about. And that’s what makes living abroad so fascinating. You find yourself gaining fresh perspective on everything from Palestine to the media to whether the proper low cholesterol diet revolves around red wine, dark chocolate, and high-quality ham (as my Spanish doctor advises). Of course, it’s a two-way street, and I share my foreign viewpoint with local friends. Lately, they’ve all been asking what happened in the last American election. Where do I start? Although I attempt to frame things in a rational context, I suspect that’s one facet of American culture that will forever remain as baffling to them as my inability to embrace bad art and big hair. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY Let’s face it, we all do incredibly foolish things on occasion. Back in the 1960s many of us spent years experimenting with dubious substances that makes me wonder, in retrospect, how any of us made it into the 1970s alive and with more than six functioning brain cells. And think about all the ludicrous risks travelers take nowadays to get a unique selfie. Thank God we didn’t have selfies during the 1960s or the human race might have died out altogether. Why would someone who is (presumably) fairly sane and possibly not even stoned suddenly decide to cozy up to a leopard or balance on a narrow ledge above a deadly drop? I believe it’s about transforming yourself from a dentist or short order cook or failing student into someone extraordinary — a symbol of bold adventure and derring-do. Symbolic acts add tremendous richness and meaning to our lives. Placing flowers on a grave keeps a cherished memory alive. Accepting on an engagement ring represents commitment and (ideally) fidelity. Seville’s bullring proudly displays a statue of the legendary bullfighter Curro Romero depicted in skin tight pants that indicate he is exceedingly well endowed, an exaggeration used to signify his manliness. (Naturally this has given rise to countless jokes and selfies.) Like Curro Romero’s trousers, the stature of many symbols is inflated out of all proportion. The 45th President once tweeted, “No one should be allowed to burn the American flag – if they do there should be consequences – perhaps loss of citizenship or a year in jail.” Really? Will that be before or after you overturn the Supreme Court ruling that that defined flag burning as a form of free speech protected under the US Constitution? I have no desire to burn a flag, but it’s comforting to know that, as a US citizen, my rights supersede those of a rectangle of cloth. Not everyone agrees with the ruling, or about which rectangle of cloth is more important than our civil rights. In 2015, a group of Confederate flag supporters went on a wild, two-day spree through the suburbs of Atlanta, Georgia, drinking, brandishing firearms, and shouting racial slurs at African Americans. Eventually they burst into a little girl’s birthday party, holding the children and their parents at gunpoint, screaming racially charged death threats. This week two ringleaders, Kayla Norton and Jose Torres, were sentenced to jail and permanently banished from Douglas County where the incident took place. Watching Norton’s tearful apology to her victims, Rich said, “She’s sorry all right. Sorry she got caught.” No doubt that’s true. But there may also be a part of her that is appalled to realize that she did, in fact, walk back to the truck, grab a shotgun, load it, hand it to Torres, and stand there screaming death threats laced with the n-word while he pointed his weapon at the terrified families. How could she and her companions do that to eight-year-olds at a birthday party — or to anyone? Such acts become possible only when you stop thinking of people as ordinary individuals and start defining them as enemies who are less than human. This happens whenever we go to war. We become driven by symbolic thinking and reason takes a back seat. Each side portrays the other as barbarians slavering to commit grisly atrocities against the innocent. The more outlandish the rhetoric, the easier it is to justify the war, encourage enlistment, raise money, bolster civilian morale, and strengthen the fighting spirit of our soldiers. Every war is positioned as the ultimate battle between good (us) and evil (them). And to do that, we re-define “them” as inhuman. So what happens when you have a nation perpetually at war? If you count all the conflicts at home and abroad, America has been at war 93% of the time since its founding in 1776; we’ve had a total of just 21 years of true peace in our entire history. We live in a constant state of mobilization against the (ever-changing) enemy —which means we live in a permanent state of symbolic thinking, being told our side is fighting to save civilization from inhuman monsters. I grew up during the Vietnam war, the first major conflict covered by nightly television news. It made my generation acutely aware that war is not glorious and can often be a moral quagmire. Today we’re flooded with information about the world, and it’s difficult to know what to think, especially about other countries. That’s why I encourage people to go abroad and see for themselves what's out there. The world is not, as the old maps pictured it, a few patches of familiar terrain surrounded by blank spaces marked “Here there be dragons.” It’s a vast and varied place filled with humans who are, for the most part, no better or worse than we are — and just as keen to take the perfect selfie. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY

|

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|