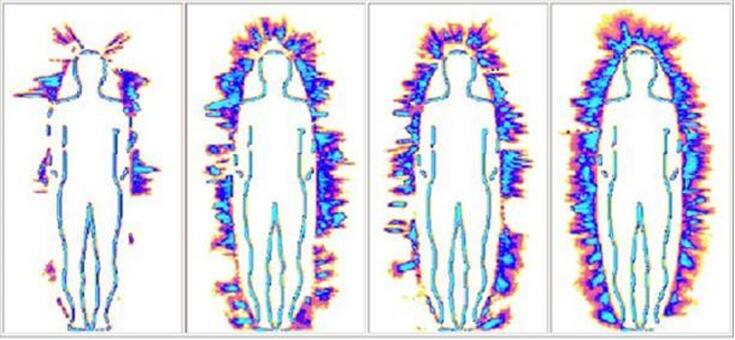

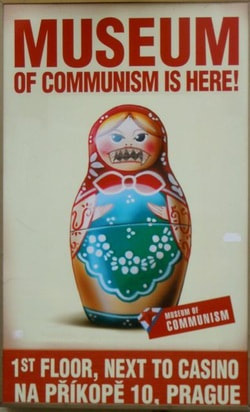

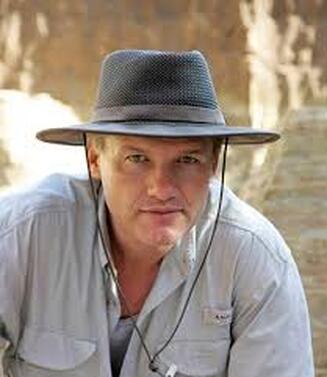

Sam Osmanagich, a Bosnian businessman based in Houston since 1992 and dressing as Indian Jones since becoming an amateur archaeologist in 2005. Sam Osmanagich, a Bosnian businessman based in Houston since 1992 and dressing as Indian Jones since becoming an amateur archaeologist in 2005. Growing up in California, I was steeped in the culture of goofy roadside attractions involving ghosts, aliens, Bigfoot, and ancient, unfathomable mysteries recently invented by hucksters who’d like to sell you a ticket and a t-shirt. So you can imagine how my internal radar pinged the moment I first beheld a lurid color poster promoting the Bosnian Pyramids. I could hardly wait to Google them. “They’re supposedly much bigger and way older than Egypt’s pyramids,” I told Rich. “Apparently they are energy amplifiers that can heal your body, your chakras, and your aura.” The Bosnian Pyramids were “discovered” (naysayers claim invented) in 2005 by Sam Osmanagich, a Bosnian business man who declared the cluster of pointy hills near Sarajevo "the greatest pyramidal complex ever built on the face of the earth." His announcement caused a sensation, providing a huge boost to national pride — and tourism — in the aftermath of the devastating Bosnian War of 1992-1995. Supporting Osmanagich’s claims became a litmus test of patriotism in many circles. Just last night a local man told me the pyramids were a national treasure and the first thing we should visit in the region. He takes his little daughter there every year for a general cleansing. The scientific community has spent years vigorously protesting that Osmanagich is perpetrating "a cruel hoax on an unsuspecting public." As Boston University archaeologist Curtis Runnels put it, “All of the ‘finds’ being made by Osmanagich are either natural features like rocks, or the result of long occupation in these valleys by people since the Greco-Roman period. As for the supernatural powers he claims for these ‘pyramids,’ one only has to note that Mr. Osmanagich published a book claiming the Maya came from the Pleiades constellation.” Nevertheless, tourists happily continue to flock to the site, and Osmanagich happily continues to collect the entrance fees, sell them t-shirts, and assure them their auras have never looked better. “We should go to the pyramids,” I said to Rich. “Maybe we’ll be the first to see Bigfoot there.” But before organizing an expedition to the pyramids, I thought it would be fun to research roadside attractions right here in Sarajevo. And it turns out the town has some doozies. The ICAR Canned Beef Monument stands as an ironic tribute to the horrendous food sent over as humanitarian aid during the Siege of Sarajevo, which lasted three years, ten months, three weeks, and three days. Yes, the UN meant well. But they delivered rations left over from the Vietnam conflict that were 20 years past their expiration date. They shipped in tins of pork, which couldn’t be eaten by the Muslim half of the population. And then there were the cans of something called ICAR beef, reportedly so foul even starving dogs wouldn’t touch it. One blogger 's grandfather told him, “If there is another siege, I would rather die than eat ICAR.” After the war, the “grateful citizens of Sarajevo” put up this monument, a meter-high replica of the ICAR beef can, which sadly, or perhaps appropriately, has fallen into a dreadful state of disrepair.  Amanpour in 1992 Amanpour in 1992 Less than a block away stands another icon of the war, the former Holiday Inn. Situated on “Sniper Alley,” one of the most dangerous roads in the besieged city, the hotel was home base for many war correspondents, including CNN’s Christiane Amanpour. "Many times it was shot by artillery fire, mortars were fired that landed on or near it, windows were broken regularly,” she said. “I remember the coffee bar, which had a canopy on top of it, in the atrium lobby was hit and caught fire." Despite the risks, and often the lack of hot water or electricity, it was the most stable factor in their lives at the time. “We considered the Holiday Inn our recreation, our home. It was where we woke up, where we went to sleep, where we visited each other, sometimes in each others' rooms. It was where love affairs blossomed, it was where we worked, it was where we escaped death. It was really everything to many of us." The Holiday Inn was considerably less exciting in 2005 when Rich and I first visited it en route to a volunteer work project. We arrived late at night by taxi, staring about us at all the bombed-out, bullet-riddled buildings — never a reassuring sight. We spent the night half-expecting the sound of artillery fire (none came), had coffee under the refurbished canopy in the atrium lobby, and departed for another city to do our work. Since then, the city of Sarajevo has been busy patching the bullet holes, rebuilding its infrastructure, and enticing tourists from around the world to enjoy its rich East-meets-West culture. The hotel's post-war recovery has been a bit more haphazard, culminating in losing its Holiday Inn branding and eventually being shut down by Bosnia's State Investigation and Protection Agency for reasons I probably don’t want to know about. We revisited a few days ago to find it in fine condition, fully restored and renamed Hotel Holiday, allowing them to capitalize on its fame without technically violating laws pertaining to terminated franchise agreements. For another blast from the past, Rich and I stopped for coffee at the Caffe Tito, a tongue-in-cheek tribute to the former Yugoslavian dictator. For an authoritarian ruler, President for Life Josip Broz Tito was surprisingly popular, a strongman who united former enemies and forged them into a socialist state with a market economy. “Yes, Tito was a dictator,” said Adis, our guide on the free walking tour the day before. “And yes, he imprisoned people and had his political enemies killed. But sometimes that’s necessary to keep a country together.” Yikes! I guess that’s one perspective. “Now that Tito’s gone, I hear there’s a lot of corruption,” someone said. Adis grinned. “You call it corruption, we call it a free market.” Caffe Tito sits by a park and playground, where we spent a few heartwarming moments watching little children climb around on old tanks and artillery weapons. Inside was a wealth of memorabilia honoring the man and his era, from his leadership of the Partisans during WWII until his death in 1980. Cult-like portraits of Tito, camouflage fabrics, and vintage weaponry rubbed shoulders with dial telephones, mid-century radios, and vinyl record albums. It was at the Caffe Tito that Rich and I took a hard look at the proposed expedition to the Bosnian Pyramids. It was 90 degrees, with humidity somewhere around 60 percent, and I was holding a glass of cold water to my forehead, wishing I had the nerve to dump it over my head right there at the table. Maybe if I slipped off behind one of the armored tanks… “Do you remember what I wrote last week about the wisdom of not climbing to high castles in hot weather? “ I said. “I’m thinking that might apply to pyramids too.” Abandoning the Bosnian Pyramid expedition was clearly the smart move. Oh sure, I had been looking forward to having my aura cleansed; it was feeling a bit grubby after all the bus rides and sweaty weather. And I was sorry now that I’d wasted minutes viewing the intro to the surprisingly dull video Bosnian pyramid SHOCK: Ancient Civilization Received Knowledge from SPACE.” Perhaps I’ll never discover the “truth” about how aliens figure into the story. But I know one thing for sure: for every once-in-a-lifetime-marvel that I skip, there are at least a dozen other, equally outlandish sites out there, just waiting for me to stumble upon them. I’m saving my strength, trusting my aura will somehow recuperate without paranormal assistance, and keeping my eyes open for signs pointing to the next offbeat roadside attraction, wherever it may be. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENOY THE OFFBEAT ROADSIDE ATTRACTIONS OF This Adventure is Just One Stop on OUR MEDITERRANEAN COMFORT FOOD TOUR Days on the road: 102 Current location: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Traditional recipes posted: 15 See all posts about the Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. See all recipes and videos. Don't miss a single loony adventure or the next mouthwatering recipe. Sign up below for updates. Thanks for joining us on the journey.

10 Comments

“Whatever you do, don’t cross her,” Rich said, after our first encounter with the manager of our hotel in Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina. This formidable woman had issued a flurry of instructions and left a large, laminated card in our room listing more rules. No cooking in the room, despite the fact we had a suite with a full kitchen. No guests in the room, which made us wonder why the table offered seating for four and the massive leatherette couch could easily hold eight. No doing laundry in the room, even though there was a washing machine in the bathroom; she’d snapped off the washer’s door handle so we wouldn’t be tempted to transgress. “Guests are required to report and compensate for any damage caused by their inappropriate behavior,” warned the rule card. Yes, ma’am! After months of warm, make-yourself-at-home-have-a-glass-of-homemade-brandy hospitality, we were gobsmacked to find ourselves sneaking food into our room and doing clandestine laundry. But if we’ve learned anything on this trip, it’s the importance of flexibility. This Monday, July 29, we’ll hit the 100 day mark, the longest time we’ve ever been on the road. We thought we were fairly travel savvy before, but this journey has brought us fresh insights about packing, food, and comfort. Like what, for instance? Well, here are a few highlights. Packing Electronics account for about a third of the weight of my suitcase, and I’ve figured out how to eliminate an entire device: by downloading the Kindle app onto my phone. My iPhone 7 plus has an oversize screen, which is a bit more comfortable for reading than standard models. Try yours and see what you think. They say no battle plan survives first contact with the enemy, and much the same could be said for travel wardrobes. I packed for a range of weather but didn’t foresee that 2019 would be the hottest summer in the history of the world. I’ve jettisoned garments I needed in April (heavy socks, long-sleeved T-shirts) to make room for a sundress and low-cut socks. What about the discards? I left them in public places, such as bus station restrooms, where others are likely to find them and take them home. I’m comfortable living out of a suitcase but every once in a while it's refreshing to leave my bag behind (stored in lodgings we’d just checked out of). We did this during the detour to Kosovo and our farmstay in Reç, Albania. If you’ve ever toyed with the idea of luggage-free travel, an overnight stay is a low-risk way to give it a whirl. Food In the past, my research about local cuisine consisted mainly of finding a few common menu items I might actually want to order. Which is why I lived on sarma (stuffed cabbage) and shopska salad last time I traveled through Eastern Europe. Now I study Wikipedia and travel blogs to learn about regional classics and their backstory. Meals are far more interesting when you know that the trout on your plate was swimming in the river beside the restaurant just hours ago, or that locals have been known to come to blows over references to ćevapi as sausage. In many places we’ve visited lately, most locals rarely go out for anything except coffee or ice cream, and when they do splurge on a restaurant meal, they expect a real feast. Rich and I generally share an entrée and remind ourselves that we aren’t obliged to finish every bite or bottle that lands on our table. When we stay in, we make light meals to give our digestive systems a bit of a rest. In short, we pace ourselves. Comfort Like eating, sightseeing is best approached, as the Spanish put it, “poco a poco,” little by little. As an energetic person and die-hard optimist, I’m tempted to believe I can do everything. But I’ve learned to take each journey as an opportunity to evaluate and honor the current parameters of my capacities. Twice lately I’ve hiked up to high castles in 90 degree heat and seriously regretted it. I’ve vowed to be more sensible in the future. Our ability to navigate well in strange places often depends on the weather, the kindness of strangers, and sheer dumb luck. But we can do a few things to hedge our bets, and one of them is making a point of arriving early for trains and buses. Who needs the stress of running through sweltering streets, dragging a suitcase, racing the clock? I greatly prefer strolling into a station and leisurely consulting the departure board and a few humans to verify that I’m waiting in the right place at the right time. Should things go south — like the train that was cancelled out from under us in Elbasan, Albania — I’m in a better frame of mind to regroup. Travel reminds us that we have remarkably little control over anything. Our grasp of the language, food, customs, money, social norms, and historical context are usually hazy at best. On a good day, we have the presence of mind to recall that we’re there for the fun of trying to unravel the mystery. Here are a few of the conundrums we attempted to grapple with during our time in Albania. Follow Your Curiosity Traveling with a purpose has added a lot of zest to our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. How might your next trip be different if you set out to follow your curiosity? You might be intrigued by classic diners in the US, want to visit the settings for all your favorite British whodunits, or feel the urge to explore ancient battlefields and figure out how it all happened (and how you could have done it better). Pursuing a goal offers countless opportunities to connect with fellow aficionados, explore unusual parts of the culture, and feel the satisfaction of completing a quest. How do you begin? Google your interest and your destination and see what comes up. Are you intrigued by the paranormal? Search for ghost tours and you’ll find nearly 35 million results in Italy alone (although to be fair, some of those are more about zombies). Staying at an Airbnb? Let your hosts know about your interests using the form Airbnb sends you when you book. I’ve used it often over the last 100 days to ask about traditional food and restaurants; I’ve received suggestions, even invitations to coffee, dinner, and excursions. If you open up the conversation, you never know where it will lead. Of course, not all suggestions prove helpful. The Mostar hotel manager directed us to the most touristy places in town, praising their views of the Old Bridge. She had an opinion about everything and wasn’t shy about sharing. Her views on dogs, which arose when friends came to collect us for lunch Tuesday accompanied by their exceedingly well-trained service animal, grew nearly apoplectic. “Impossible! Dogs? In a hotel? No! Impossible!” Fortunately, Rich and I had discovered a delightful, shady little restaurant, with a view of the river (if not the Old Bridge), a dog-friendly policy, and a large fan with a tub of water that spread a fine, cooling mist in all directions. As the owner passed around complementary aperitifs, I reflected that these are the best lessons we can learn on the road: how to ignore bad advice, break ridiculous rules, and enjoy ourselves in our own way, wherever we are. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY I wrote this in Mostar, a city Bosnia and Herzegovina, during my 2019 Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour.

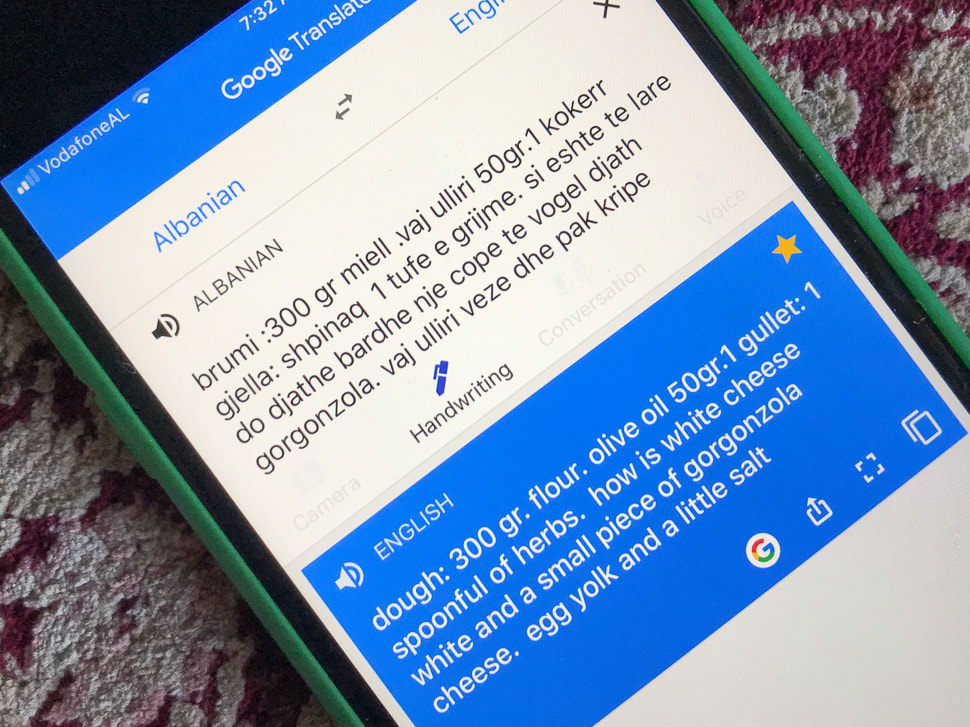

See all posts about the Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. See all related recipes and videos. If you haven't already subscribed, sign up so you don't miss a single loony adventure or the next mouthwatering recipe. HOW TO GET UPDATES My automatic sign-up form is on the fritz. If you would like to subscribe to my blog and get notices when I publish, just send me an email. I'll take it from there. [email protected] “You want coffee now?” Our waiter could not conceal his astonishment. “With breakfast?” Too well-trained to roll his eyes, the waiter (who also served as the desk clerk of our hotel in Durrës, Albania) murmured, "Right away, madam" in a way that spoke volumes. He disappeared into the back, ostensibly to fetch the coffee but actually to regale his co-workers with this latest proof of foreigners' barbaric ways. I’m always tripping over this stuff in the Balkans. After months on the road exploring culture through cuisine (our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour just hit the 90 day mark!) I’ve learned that around here you drink liquid yogurt or a large glass of warm milk at breakfast and take your coffee at dawn or much later in the morning, usually in a café. And not just any café. It turns out the vast majority are all-male preserves where weighty subjects — business contracts, politics, car repairs, gossip about sports figures — are discussed. Could I go into one and get served? Yes, and I’ve done it, accidentally; everyone was very polite. But gatecrashing guys’ hangouts isn’t as amusing as it may sound. Occasionally I run across an all-women’s café, but that’s awkward for Rich. We sometimes pass up a dozen places before we find one where we’ll both feel comfortable. In rural villages, the question doesn’t arise because women only drink coffee at home. Country families still tend to follow the old ways, defined for 500 years by the Kanun, which held that women were property and could not sign contracts, wear a watch, smoke, or vote in elections, to name but a few. (Don’t get me started on how I feel about this.) I'll give Northern Albania credit for coming up with one unusual alternative: a woman could become a “sworn virgin” who assumed the dress, demeanor, and legal rights of a man, a lifetime commitment that included a vow of celibacy. In the past, some women did this to acquire the legal right to serve as the head of a family or business; for the handful following this path now, it tends to be more a lifestyle choice. Luckily, modern Albanian women have a far wider range of rights and opportunities than their foremothers. Lots of them are earning good money in agrotourism, providing meals and/or overnight stays in rural homes so visitors from more industrialized settings can appreciate the full “farm-to-fork” experience. Which is how, on a recent rainy afternoon, I found myself hanging around an outdoor kitchen with Emanuela, a full-time professional chef who spends her evenings preparing dinner for a dozen people at her brother Florian’s guesthouse. [See recipes here] Florian told me his guesthouse was the first ever to open in Albania. It's just a few miles outside of Shkodër, one of the most ancient cities in the Balkans. Few of the city's glorious old buildings remain, and most visitors zip through it on the way to the Albanian Alps, also known as the Accursed Mountains, which offer the kind of vigorous hiking over treacherous terrain that Rich and I prefer to avoid at all costs. Instead, we chose to idle away a few days in the old city visiting museums, markets, parks, and of course, coffee houses. We often saw women from the countryside wearing traditional ethnic dress, men driving horse-drawn carts laden with charcoal or hay, and one robust figure, observed lingering over a beer every morning at a small café, whom we were half convinced was a sworn virgin. Rich and I were comfortably ensconced in a downtown hotel dating back to 1694, enjoying meals served in the old courtyard by a staff willing to provide coffee with breakfast and without attitude. However, being selflessly devoted to doing comfort food research on behalf of our readers, we pried ourselves out of this cozy spot for one night so that we could sleep in a rural guest house rumored to have a particularly high standard of old-fashioned country cooking. Our hostess, Zina, turned out to be a woman about my own age who spoke no English; luckily her daughter-in-law, Diana, was on hand to do the necessary translating. The first thing they asked was whether we wanted any coffee. When I said yes, Zina quickly produced tiny cups of espresso and glasses of raki, homemade fruit brandy with throat searing flavor and an alcohol content somewhere to the north of zowie! I took a cautions sip. When I had recovered my powers of speech, I said to Diana, “I can never tell when to drink raki. Some people say before a meal to prepare the stomach. Others say after to improve digestion. Last night someone suggested it with our meal. I’ve also heard it’s always drunk with coffee.” “I have raki every morning with my coffee,” said Diana. “It helps me start my day.” “Where do you work?” “I teach English in a school.” I wondered if any of my old schoolteachers ever did the same; it would explain a lot. The house was spacious and impeccably clean, every window offering views of mountains, cornfields, and the vast chestnut forest Pylli I Gështenjave. Our bedroom held old-fashioned wooden furniture including a wardrobe big enough to contain all of Narnia. It was wasted on us, as this was one of our luggage-free trips, but we appreciated the thought. The online description had mentioned a private bathroom, but as we’d discovered before, “private” can be used in the sense that the bathroom is not open to the general public rather than actually being en suite. Fortunately, we were the only guests and we had not only the bathroom but the entire upper floor to ourselves. Downstairs, Zina welcomed us into her kitchen, and I am pleased to report that her husband Mirash pitched in with the cooking and spent a lot of time taking care of Diana’s four month old daughter. The food was prepared on a wood-burning stove, and involved such intensive labor, so much variety, and such massive quantities, that we gorged ourselves to bursting and still felt horribly guilty that we weren’t able to consume more than a small fraction of what was on the table. [See recipes here] “I’m never going to eat again,” Rich muttered, as we staggered upstairs after dinner. But Zina had other ideas. The next morning, after Rich and I had ambled around making friends with the family’s animals, she presenting us with an enormous breakfast of pancakes with homemade fruit compote and honey, fried eggs, slabs of smoky cheese, and large glasses of hot, fresh milk with little pools of butterfat floating on the surface. “It’s like drinking it directly from Lara’s udder,” I said with a shudder. “I really can’t.” To my astonishment and admiration, Rich manfully downed his glass. “My parents gave me warm milk as a kid,” he said. “I’m not crazy about it, but I can drink the stuff.” And that’s the beauty of travel. You learn things about each other that somehow never came up, even in 34 years of conversation. Rich may credit his upbringing, but I know the real reason he was able to belly up to that milk so cheerfully: before breakfast, he’d downed a glass of raki with his early morning coffee. “I can never figure out when to drink what,” he said. “But I know why I’m drinking it: because it’s there.” And I suppose that’s as good a policy as any. Is your mouth watering? Want to try making these dishes at home? See Emanuela's and Zina's Albanian Farmhouse recipes here. Rich and I bid a fond farewell to Albania and traveled by bus to Bosnia & and Herzegovina, where we are looking forward to more adventures and great comfort food. We're also hoping for better wifi, as connection has been a bit iffy in recent weeks, which is why I haven't posted much on Facebook and sometimes don't reply to comments right away. Today marks our 90th day on the road! Take a stroll back through some of the highlights. See all posts about the Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. See all recipes and videos. If you haven't already subscribed, sign up here so you don't miss a single loony adventure or the next mouthwatering recipe. Thanks for joining us on the journey. Four years ago, my husband — and I say this lovingly — became obsessed with an Albanian restaurant called Ali Kali. “The owner brings in your food riding on the back of a trick horse,” he said. “Ali Kali means Ali’s Horse. It’s fantastic. We’ve gotta go.” “I’m in, obviously. Where is it?” We were in California at the time, and I thought maybe this was the latest LA fad. “On the coast of central Albania.” “Oh good. So only 10,000 kilometers from here.” For us, getting there is half (often three quarters) of the fun. But I was just a teensy bit concerned about how we were going to navigate once we arrived in Albania. Trains are our favorite form of travel, but I’d read that their railway system was being dismantled bit by bit so the nation could devote more of its transportation resources to new superhighways. We soon discovered to our dismay that this was only too true, as demonstrated by these photos from the railway station in Durrës, the transportation hub of the nation. There was still one Albanian railway line in operation, so after our visit to Korçë, we just had to figure out how to travel 77 miles to the town of Elbasan, where we could catch the 1:30 train to the port of Durrës, which would put us within a taxi ride of Ali Kali. “The only way to get to Elbasan is by furgon,” Rich reported after an online investigation. “It’s a kind of unofficial minivan; you have to ask around and someone will point out the right vehicle. They won’t depart until all the seats are filled, however long that takes.” I knew from our trip to Kosovo that air conditioning would, at best, mean opening a window or door. Temperatures in Elbasan were predicted to hit 100. Call us wimps, but we hired a car and driver from a reputable service. Even this relatively luxurious form of transportation had potential drawbacks. “The greatest risk most people in Albania face is on the roads, where traffic accidents are very frequent and the fatality rate is one of the highest in Europe,” our guide book observed helpfully. “Until a few years ago, Albanian roads were so bad that it was difficult to drive fast enough to kill anyone. Now, though, cars zip along newly upgraded highways that are also used by villagers and their livestock. There is no stigma attached to drink-driving and practically no attempt is made to check it.” Yikes! Obviously we’d be lucky to reach Elbasan alive, never mind getting all the way to Ali Kali. As it turned out, the standard of driving we saw was no more alarming that you’d find on, say, the New Jersey turnpike. Our driver, Reoland A., was professional, competent, and a thoroughly nice guy. So Rich and I were lulled into a state of tranquility that was abruptly shattered when we arrived in Elbasan to discover that the afternoon train had been cancelled. According to men in a nearby café, there weren’t enough passengers to justify the petrol. Reoland (bless him!) ended up driving us all the way to Durrës, and by the time we arrived, he not only knew all about our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour, but we’d arranged for he and his wife, Irmira, to join us at Ali Kali a few days later. After four years of anticipation, I wondered, would the place live up to Rich’s expectations? “Even better than I’d hoped,” Rich said happily. Our expectations were far lower about visiting the capital city, Tirana. I’d read it was drab and utilitarian, relieved only by swaths of garish paint applied to concrete apartment blocks in a project designed to distract the eye from an otherwise the grim landscape. Spearheaded in 2000 by then-mayor and later prime minister Edi Rama, the paint project wasn’t universally popular, according to our guide book. “The colours and patterns became livelier and livelier, until even the more progressive of Tirana’s citizens began to complain that their city was starting to look like a circus.” Once again, I beg to differ with the guide book (which to be fair was five years out of date). The moment I saw Tirana's vibrant buildings, I fell in love with the whole wacky concept — amateurish execution, eye-popping designs, and all. To me, the zingy buildings reflect the city's abundant energy and all-out determination to transform itself into a world-class city. They seem to be making considerable progress. The highway between the port of Durrës and the capital is lined with gigantic, glittering corporate headquarters. The boulevards leading to Tirana's city center are shaded by tall trees that hide some of the less fortunate architectural efforts of the past. Sophisticated bars, restaurants, and shops are springing up all over the downtown area. As for coffee houses, in 2016, Albania surpassed Spain as the country with the most coffee houses per capita in the world. The city has come a long way since the dark gray days of communist dictator Enver Hoxha, who ruled the country from 1944 until his death in 1986. He isolated his country from the USSR because he decided the Russians had become too ideologically slack, and from the rest of the world because it was too corrupt. His Sigurimi secret police constantly spied on citizens, and the slightest infraction, such as listening to an Italian song on the radio, could land you in prison or a concentration camp. Part of Tirana’s makeover includes new museums that tell the story of those dark times, so that residents and visitors born in happier circumstances don’t forget the past and find themselves condemned to repeat it. The museums are part of the city’s strenuous, ongoing efforts to attract tourists. It’s a work in progress. Officials have dubbed Tirana “The Place Beyond Belief,” which strikes me as the sort of ambiguous nickname that could easily come back to haunt them in later years. No matter, the city’s economy is in growth mode now, and residents and visitors are flocking to the glamorous new bars and world-class restaurants that have sprung up in the past few years. Reoland and Irmira joined us for a visit to Ceren Ismet Shehu, one of the area’s hottest new venues, on a hillside overlooking the city. “I went to the UK and started as a dishwasher,” chef/owner Ismet Shehu told me with a grin. “I worked my way up to chef. Then two years ago I came home and made this restaurant for my family. I didn’t tell my mother until it was ready; I brought her here as a surprise.” The appetizers included spinach burek, goat stuffed with quail eggs, layered flia pastry, cheese with blueberries, fig rounds, pink pasta stuffed with green cheese, yogurt dip, and more. The lamb, slowly simmered in milk inside a clay pot, was soft, succulent, and melting off the bone. “Well?” I asked Rich afterwards. “It was the best lamb I’ve ever tasted,” he said. “But you know what would have made it even better? Being carried in on the back of a horse.” So that’s our new restaurant standard, my friends. From now on, equine presentation is the benchmark against which we’ll be judging all future dining experiences. I’ll let you know how they measure up. UPDATE ON OUR MEDITERRANEAN COMFORT FOOD TOUR Days on the road: 82 Countries visited (so far): Greece, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Albania Equestrian restaurants: 1 We left Tirana this morning and headed north to a remote village in the mountains. Stay tuned! See all posts about the Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. See all recipes and videos. If you haven't already subscribed, sign up here so you don't miss a single loony adventure or the next mouthwatering recipe. Thanks for joining us on the journey. Some readers (and you know who you are) have expressed skepticism about our visit to Albania. “Why?” and “Are you nuts?” are among the milder comments I’ve received. “There’s nothing to see there,” a Spanish friend insisted. I beg to differ. Last Friday we entered Albania over wooded mountains, descending into a broad green valley filled with working farms. Horses pulled ploughs and carts. Flocks of sheep and goats ambled beside the road. Men and women stood waist-deep in fields of purple flowers, harvesting blossoms and spreading them out to dry. Haystacks stood beside cottages that looked like illustrations from medieval fairy tales. “Did we just go back in time?” said Rich. Time seems to operate differently in the Balkans, and our destination, the lively, cosmopolitan city of Korçë, was no exception. Its checkered past included centuries of Ottoman rule, occupation by various European powers, and a grim isolationist period under communism. Having managed to remain separate from the USSR, Albania was fortunate enough to escape the ghastly Soviet brutalist architecture, so the visible reminders of Korçë’s history showed its Ottoman and European heritage. When freedom was declared in 1990, the city set to work sprucing itself up — painting buildings, expanding parks, adding daring new architecture, and opening shops, bars, and coffee houses galore. All this plus low prices has made Korçë a popular regional vacation destination. But American visitors remain so rare that people would stop us on the street to exclaim, with surprise and pleasure, “Hey, did I hear you speaking English?” Normally, I’d expect this to be followed by solicitations for money, inappropriate sex, or worse, but in Korçë, people simply wanted to chat with us for the sheer novelty value. Of course, having practically no English-speaking visitors meant practically no English-speaking locals in service jobs, such as running our hotel. Fortunately, my family is big on charades, so upon meeting our hosts, Elena and George, I easily pantomimed my pleasure at finding that our room was spacious, sunny, and blessed with a balcony overlooking a tree-lined boulevard. Rich produced a credit card, and here we hit a snag: the hotel only took cash and we had no local currency. “Bank?” said Rich. George and Elena nodded their understanding but were stumped as to where we might find such a thing. They took us outside and flagged down passing strangers, who looked equally dumbfounded by the question. A guy in a nearby shop added his two cents worth, and in no time there were eleven (I counted) people working on the problem. Eventually a group of women led us to an ATM five blocks away. From the ATM Rich and I went on to lunch, so it was only later that I had a chance to check out our accommodations more thoroughly and discover the full, hideous reality of our shower. It was sparkling new and perched at the top of a flight of polished marble stairs, with no handrail. Instantly I pictured myself descending those slick steps with damp, slightly soapy feet and toppling to my doom. Stark naked, soaking wet, and crashing onto a bidet was not the way I wanted to go out. “If you’re really concerned, we can always move to another hotel,” Rich said soothingly. “I know of one near here; we’ll go check it out.” And that’s how we came to pay our first visit to Bujtina Sidheri, a marvelously atmospheric old hotel and restaurant with rough stone walls, beamed ceilings, and small, old-fashioned bedrooms. I could tell Rich wasn’t keen to move there because he instantly came up with a plan for emailing our current hotel, which prior correspondence showed had someone online capable of communicating in English. We could request another room with a more conventional shower, he suggested, citing my not-entirely-fictitious issue with mild vertigo. “But we should come back here to eat,” he said. “Online reviews say the food is great.” The next morning Elena and George delivered a homemade breakfast to our room and conveyed via hand gestures that we were free to use the floor-level shower in the room across the hall. That’s when it dawned on us that we were the only guests in the hotel, which was deserted and eerily silent at all times. As was Bujtina Sidheri when we returned to it that night. Eventually we tracked down Griselda, the young woman who had shown us around the day before. Hastily concealing her surprise at seeing actual dinner guests, she escorted us to a table. There followed an elaborate interchange via pantomime, Google Translate, and smartphone photos, then Griselda disappeared in the direction of the kitchen. “What did we just order?” I asked. “Who knows? I’m sure it will be wonderful,” Rich said. It was. Our salad had elegant slivers of apple, cantaloupe, strawberry, kiwi, and orange, some cherries, and a chunk of magnificent Gorgonzola, all drizzled with a balsamic vinaigrette. Rich’s pork came topped with avocado, pomegranate, and fresh dill. My chicken rollups were tender and perfectly sauced with a creamy chicken broth, a scattering of pomegranate seeds, a dusting of poppy seeds, and a pansy. We’d just begun tucking into the salads when two musicians arrived with guitars. After a bit of banter with Griselda and cheerful nods to us, they sat down and began to play. The lighthearted folk music danced through the rooms, as perfect an accompaniment to the meal as the crisp white wine. [Want to hear the tunes? Check out my video below.] After spice cake with brandied pear, I used Google Translate to tell Griselda I was a travel writer and ask if I could return the next day to film the magic happening in the kitchen. She nodded enthusiastically. We set a time. And then the conversation floundered over the question of what would be prepared. The only word I clearly recognized in Google's English translation was “cheeks.” I nodded and the matter was settled. “You think she meant pork cheeks?” I asked Rich afterwards. “You mean like the carrillada we eat in Seville? Who knows?” Upon our return, we discovered Griselda was making spinach pie. Rich was aghast. “But we just filmed spinach pie in Bitola. Are you OK to do a repeat?” I shrugged. “Let’s roll with it and hope for the best.” We soon learned that the two pies do share a common tradition but vary wildly in execution. Griselda worked with two other cooks, Julia and Vida, their tasks as perfectly choreographed as a ballet. Together they created a streamlined version of spinach pie in just half an hour. It was twice-baked and emerged from the oven puffed up to enormous proportions, hissing steam like an outraged dragon. Afterwards, as Rich and I sighed blissfully over the warm, flaky pastry and lush filling, I reflected that Albania was rather like this twice-baked spinach pie. It wasn’t at all what I’d originally expected, but it turned out to be absolutely wonderful — deeply traditional yet wholly original, surprising yet comforting. Our entire visit to Korçë had proved to be safe, fun, friendly, blessed with good food, and filled with quirky moments. And that's just the way I like it. [Recipe: Griselda's Twice-Baked Spinach Pie] UPDATE ON OUR MEDITERRANEAN COMFORT FOOD TOUR Days on the road: 75 Hotels & Airbnbs: 21 Buses: 13 Ferries: 6 Trains: 3 Trains canceled out from under us: 2 Memorable meals: too many to count We've now left Korçë and moved west to Durrës, Albainia's main port and a popular beach resort for Italians and residents of the Balkans. Internet access is shaky, but I'll post what I can here and on Facebook. If you haven't already subscribed, sign up here so you don't miss a single loony adventure or the next mouthwatering recipe. Thanks for joining us on the journey. |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|