|

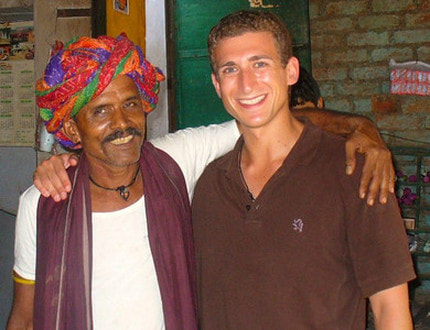

“If you really want to make a friend, go to someone’s house and eat with him,” said civil rights activist Cesar Chavez. “The people who give you their food give you their heart.” In the past, it was a bit tricky to convince strangers to allow you into their home at all, never mind asking them to provide you with a sumptuous meal, hours of sparkling conversation, and possibly a piece of their heart. But nowadays, thanks to EatWith and other meal-sharing apps, you can connect with people all over the world who love to cook and entertain. [Here's how it works.] For me, a lot of the appeal is the adventure of never knowing quite what to expect. Take last Friday, for example. Rich and I rolled into Athens late in the morning, utterly relaxed and contented after our time on the islands of Lesbos and Ikaria. That feeling lasted just about as long as it took us to pull our bags out of the taxi’s trunk and drag them to the sidewalk. Every one of the city’s 3.5 million residents seemed to be rushing furiously past us, shouting into their phones against a backdrop of graffiti so virulent that I could almost hear it howling. We had arrived a few minutes early for an EatWith luncheon and hovered on the sidewalk, feeling invisible and adrift in the crowd. “Karen?” said a voice. I turned to find our co-host, Nikos, smiling in welcome. In minutes we were on the balcony where his partner, chef Michail, stood in a flower-decked open-air kitchen, shaded with a wooden lattice and overlooking Athens and the Acropolis. Against this breathtaking backdrop, he proceeded to teach us how to cook one of his signature dishes: Corfu Pastitsada with Free-Range Rooster and Pasta. Now, I know what you’re thinking: isn’t rooster a tough old bird? Ordinarily, yes. Years of servicing hens, fighting off other roosters, breaking up fights about the pecking order, and defending the flock from the occasional hawk or racoon leaves the mature country rooster lean, mean, and leathery. That’s why Michail’s recipe calls for a younger bird, about eight months old. I’d never cooked a rooster and was delighted when our hosts agreed to let me film the whole process. Then we learned Nikos had trained as a camera man, and Rich was only too happy to share the role of videographer with someone who actually knew what he was doing. [See the full rooster recipe here.] Late that afternoon, as we bid a fond farewell to Nikos and Michail and the remains of the rooster, I reflected that the act of eating in community is — at its best — nourishing for both body and soul. This proved true all over again a few days later in a very different setting, when Rich and I volunteered at a soup kitchen run by the Caritas Athens Refugee Program. Rich and I had heard about the soup kitchen two weeks before over breakfast at our hotel on Lesbos Island. I had fallen into conversation with Ann and Linda, two American sisters (siblings, not nuns) who were on the island visiting the refugee camps. As you may recall, in 2015 tens of thousands of asylum seekers — many fleeing wars in Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan — crossed the 3.4 mile gap between Turkey and Lesvos Island on whatever boats they could find in order to seek sanctuary in the European Union. People met them on the beach with water, blankets, and tarps, but the island was quickly overwhelmed. “Refugees were sleeping everywhere, even on the sidewalks,” a local man told us. In the ensuing chaos, temporary camps were set up as a stepping stone to more permanent relocation. But years later, refugees are still arriving, and fewer are getting moved on, thanks to tougher EU policies closing down options. In the largest camp, Moria, “the overcrowding is so extreme that asylum seekers spend as much as 12 hours a day waiting in line for food that is sometimes moldy. Last week, there were about 80 people for each shower, and around 70 per toilet,” reported the NY Times. The filth, squalor, and violence have led to widespread disease and an epidemic of suicide attempts. And these two nice women had gone there? “We mostly spent time at Pikpa Camp, which is really well run,” one told me. “It’s where they send the most vulnerable refugees, who simply can’t survive at Moria.” She gave me the contact information, and with some trepidation, I emailed the camp and they kindly agreed to let us visit. Contrary to all my expectations, the visit was inspiring. Staff members Derek and María showed us around the tidy cabins, the communal garden, the kitchen, the “store” where donated clothing and supplies are given out, the tiny medical clinic. They told us about refugees learning to sew so they could transform the life jackets they’d worn on the crossing into Safe Passage Bags, which are now sold in a local shop and online. This was a refugee camp done right, a bright contrast to Moria which, when we stopped by, was just as grim as you’d expect. And no, I can’t bring myself to post any photos of that visit. When families and individuals are lucky enough to get processed out of the Lesbos camps they often wind up in Athens, where living conditions may be better but negotiating the inscruitable processing system can take long, frustrating, sometimes desperate years. Every day, hundreds get their main (often only) meal at the soup kitchen run by Caritas Athens Refugee Program. Having volunteered for years at a Cleveland soup kitchen, I thought I knew what to expect. Boy was I wrong. I haven’t worked so hard in decades! I spent half an hour peeling cloves of garlic, then three hours cleaning trays as fast as I could — as more and more kept piling up. If you’ve seen the Sorcerer’s Apprentice you’ll have a pretty good idea of the relentless pace. The staff and volunteers — Greek, British, German, Australian, American, and others — were astonishingly organized, efficient, and cheerful. The clients were mostly refugees from Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and the drought-ridden Horn of Africa, plus some Greek families who had fallen on hard times, and a handful of other Europeans. The staff made sure everyone felt welcome and respected, and while many clients seemed too shell-shocked to talk much, lots of them — especially the kids — clearly knew each other and chatted like old friends. In the brief interludes when I wasn’t frantically swabbing trays, I enjoyed the sound of the talk and laughter. To me, that’s one of the most comforting sounds in the world: people enjoying their meal and the pleasure of each other’s company. Whenever we break bread together, we establish, however briefly, a circle of community and belonging. That’s a welcome solace for anyone and doubly precious when you’re among strangers, far from the place you once called home. We've been on this journey 41 days. What a ride so far! LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR MEDITERRANEAN COMFORT FOOD TOUR. SIGN UP TO RECEIVE UPDATES AS WE GO. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY

7 Comments

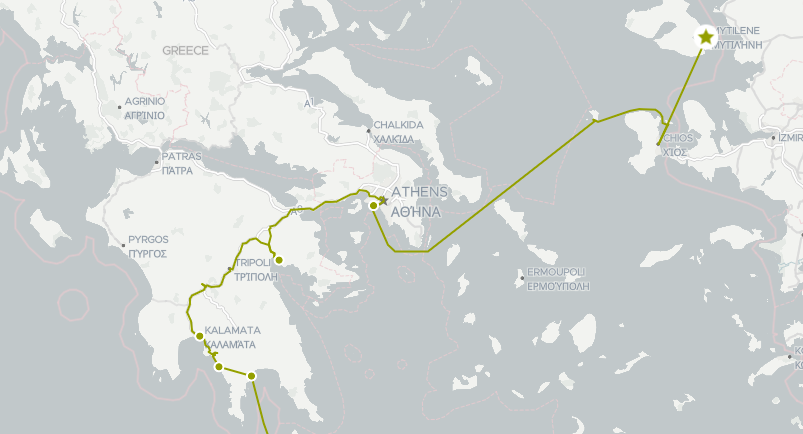

“Ya gotta give the guy credit,” I said around midnight, as Rich’s new friend led yet another 20-something woman onto the dance floor. “He’s got a lot of energy for eighty-four.” One of the locals laughed. “Eighty-four? He’s ninety-three.” I regarded the dancer with even greater respect. Not only was he the life of the panygyri, one of the traditional all-night parties with which Ikaria celebrates saints’ name days, but he was a living example of the locals’ legendary longevity. Designated as one of the handful of Blue Zones in the world, the island is full of people living remarkably long, healthy lives. I’d read articles on the subject aloud to Rich, adding, “We have to go there. Maybe it will rub off on us.” We arrived on the Sunday afternoon ferry and asked Dimitri, our hotel’s ever-helpful desk clerk, where to go for a late lunch. “Popi’s,” he said promptly. “The best food on the island, possibly all of Greece. Ten minutes’ walk up the coast road.” Twenty minutes later, as we staggered up yet another rise, we began to wonder if somehow we’d missed the place. Pulling out his phone, Rich discovered that Google had actually heard of Popi’s and informed us that it was just around the next bend, adding helpfully, “Closed. Opens again 1:00 AM.” “That can’t be right,” he said. We’d been told Ikarians refused to live by the clock, lightheartedly referring to any time of day as “late-thirty.” One young man I’d read about set off to buy coffee for his mother and didn’t return for three months. He’d run into friends en route to a panygyri, partied all night, gone to Athens, and gotten a temporary job. Presumably at some point he called home to suggest someone else should fetch Mom’s coffee. Obviously things were a bit looser around here. Still, opening at 1:00 AM? We soldiered on. Popi’s was just around the next bend, open, and serving some of the best food we’ve ever eaten. As we settled in the shade of the overhead vines, looking out over the tranquil Aegean Sea, we chatted with Zisis, whose mother had operated the place as a bar until he was born in 1993, at which point she converted it into a restaurant. I asked if he’d lived here all his life. “I went to work in Crete for a time,” Zisis told us. “Too much stress. It’s better here.” A relaxed lifestyle is one of the reasons ten times more Ikarians than Americans reach their eighties and nineties — and why their old age is rarely plagued with cancer, depression, or dementia. Another major factor is a diet based on the island’s wild greens, nutrient-rich herbs, seasonal vegetables, smaller amounts of food in general, and protein that’s mostly homemade cheese, fish, and goat. Goat is a surprisingly healthy option, far leaner than lamb or beef, with 40% less saturated fat than skinless chicken. And wild goat, it turns out, was the specialty of the house at Popi’s. Now I know what some of you are thinking: How could I consider eating one of those cute little goats that had bleated a greeting as we passed, peering curiously at us from the hillside next to the restaurant? Well, right now, Ikaria is hideously overrun with goats, thanks to EU subsidies rewarding larger herds. On an island with just 8423 residents, there are currently 35,000 goats, most roaming free and wreaking havoc on the ecosystem. Islanders are desperate to cull the herds to keep their island’s vegetation healthy. I decided to do my bit to help. “Want to try some wild goat?” I asked Rich. “Will you show me how you make it?” I asked Zisis. To my delight, they both said yes. Zisis explained the meat was super fresh, having been butchered that very morning. They raise their own goats and get more from relatives and friends. “Some goats are kept in pens, but many are free. And then the people must go hunting.” Asked to pin down quantities for the recipe, Zisis estimated he starts with about 2.25 kilos of meat. Because it’s so lean, formal cuts such as loin and shoulder aren’t practical; instead you make “village cuts,” dividing the meat any way you can, so long as it winds up a size that’s roughly suitable for cooking. You add lots of salt, pepper, and about three quarters of a cup of olive oil. You cook the meat in a ceramic pot at 200 degrees Celsius (400 degrees Fahrenheit) for an hour and a half to two hours. The cooking brings out the meat’s natural juices, but check it a few times and if it seems dry, add a little vegetable broth. When the meat is tender and the smaller bones practically liquified, you take it out of the oven and sprinkle it with fresh herbs. Often this includes oregano, which is full of vitamins, antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, digestive aids, and much more. A study showed the variety grown on the island is three times more nutrient-rich and aromatic than the kinds in other parts of Greece. (I hate to even think how our American corporate version might compare.) But the most important thing we learned is that wild goat cooked in its own juices and garnished with wild herbs tastes simply marvelous — succulent, rich, and comforting. Learning how to cook goat was just one small part of our effort to live as “Ikarianly” as possible while we’re here. We’ve eaten local foods, sampled the local wines, and danced at the panygyri. Letting go of our sense of time, we’ve been easing around town at our best approximation of the locals’ relaxed pace, stopping often to linger in cafés and on our favorite wharf-side bench. Don’t get me wrong; this isn’t an island of slackers. People get plenty done. They just do it their own way. Errands, for instance, often involve leaving their car in the middle of the street, their motorcycle at the curb with the keys in it, or their bicycle propped unsecured against a lamppost. Ikarians don’t sweat the small stuff … or the large stuff either. My goal in life is to find more ways to be like them. And of course, to eat more wild goat. “I can't think of anything that excites a greater sense of childlike wonder,” said travel writer Bill Bryson, “than to be in a country where you are ignorant of almost everything.” Few countries offer more golden opportunities for feeling utterly ignorant than Greece. The written language alone makes you feel like a toddler, staring at random shapes of letters that seem to be dancing before your eyes. The wonderment goes up exponentially when you take an overnight ferry from the mainland to arrive on a distant island shortly after dawn and before coffee. "Τώρα φθάνουμε στη Λέσβο,” announced the loudspeaker. We are arriving in Lesbos. Rich and I grabbed our bags and headed down the gangplank to the port city of Mytilene. The air was sweet and balmy, the light luminous. Was I thinking of Aristotle, Sappho, and all the brilliant minds who’d passed this way before me? Nope, I was seeking coffee. Fortunately, as the Greeks are as deeply attached to their καφές as the most passionate Starbucks addict, it took less than a minute to find a café. When the caffeine enabled me to gather my wits sufficiently, I asked, “How far is the hotel?” “About a half hour’s walk.” It was closer to 45 minutes, with the last bit uphill followed by three sets of stairs. But it was a wonderful walk, along the vast curve of the harbor where fishing boats bobbed, whistling young men pushed carts of supplies, ancient Vespas puttered by, women readied tables at wharf-side restaurants, and old men sat nursing thick ceramic mugs and hand-rolled cigarettes. Just about every café seemed to have an old dog sleeping at the threshold. The buildings were a jumble of styles: Mediterranean, old stone, Western European, ornamental Byzantine, and of course, a few boxy, 1960s-style concrete buildings because hey, this is the real world. Our hotel was a converted 1916 mansion, and I was charmed to discover we were in a tower room, one that was perfectly round, like something in a fairy tale. We deposited our bags and set out to explore the town. We soon found ourselves on Ermou Street, which was much like Harry Potter’s Diagon Alley — a blast-from-the-past jumble of fishmongers, cobblers, confectioners, and shops selling old books, Kodak film, DVDs, and “curiosities.” Presiding over one end of the street was the magnificent church of Saint Therapon the Wonderworker, a 7th century Palestinian refugee who had such a knack for curing the sick that his miracles are still much in demand today. At the other end of Ermou Street was the old harbor and some fish restaurants; lunch instantly moved to the top of our agenda. We settled at a wooden table covered with a blue checked cloth and studied the menu. Grilled sardines, we decided, and at the waiter’s urging, a fish I’d never tried before: red mullet. Less romantically known by its common name — the bottom-feeding goatfish — red mullet is a tender, tasty fish that in ancient times rose to an extraordinary trendiness among wealthy Romans. Top specimens were sold for their weight in silver, kept in ponds, and caressed by their owner, who would brag to friends about teaching the fish to come to the sound of his voice. (Having owned goldfish, I can tell you that most fish will come to signals associated with food, so this doesn’t imply special brilliance on the part of red mullets. Or their owners.) Great thinkers of the day — Seneca, Pliny, Cicero —discoursed on the red mullet’s charms, and artists were commissioned to include their image in mosaics. But for us, they were simply lunch. The recipe is ridiculously simple: dust the red mullet with flour and salt, fry in oil, serve with lemon. It’s possible that the island’s most famous resident — the poet Sappho — wrote odes to the red mullet, but we’ll likely never know, as nearly all her work has been lost since her death around 570 BC. Sappho was born to a wealthy Lesbos family and her talent took the ancient world by storm. Many of her poems speak eloquently of love and desire between women, which naturally led to assumptions about Sappho’s own sexuality, giving rise to the term lesbian. This has driven some conservative residents of Lesbos absolutely bonkers, especially with the rise of the LGBTQ movement in the 20th century. In 2008 a group of Lesbos islanders tried to get a legal injunction banning groups from using the world lesbian in their names, claiming it violated their human rights by associating the island with “disgraceful” practices. As you can imagine, they were laughed out of court and have had to satisfy themselves with making sure everyone spells it Lesvos, a more accurate transliteration of the Greek Λέσβο. Despite their best efforts, there’s a modest but growing LGBTQ tourism trade, supported by agencies such as Sappho Travel in Skala Eressos, Sappho’s birthplace. Today, the island’s most famous export isn’t poetry but ouzo, a dry anise-flavored aperitif. Lesbos boasts 17 ouzo factories, some quite large, others no bigger than a kitchen; together they produce half the nation’s supply. We’d heard it was traditional to drink ouzo around sunset and that a good place for this was Kastro Tavern, owned by a magician named Georgios. We arrived at dusk to find Georgios playing backgammon with friends, his dog asleep in the kitchen, and no other customers in sight. “We’d like some ouzo,” I said. “Do you have Kefi?” This popular brand is named for the state of sublime, transformative contentment when everything in the world seems right. “No,” said George. “It is turned off.” He mimed closing a tap. “Two brothers made it, and they …” He made fists and pantomimed punched them together. “No more Kefi.” Well, that’s one for the irony department, I thought. We chose another brand at random. “Ice?” asked George. “Of course,” I said. I’d read that ouzo, which we’d been taking neat, should always be served over ice or with a little cold water, which turns the clear liquid cloudy. Why is this important? I have no idea, but I’m not about to fly in the face of tradition. It’s also meant to be taken with a meze (snack) or two; at 37% to 50% alcohol content, it’s nothing to be trifled with. We ordered white beans and red mullet, and sat sipping, nibbling, and listening to the clatter of dice and the low hum of talk and laughter. Occasionally George’s dog wandered over so Rich could scratch behind its ears. When we eventually bestirred ourselves to ask for the bill, George said, “Would you like to see magic?” He dazzled us with nifty bits of sleight of hand. “The bag is empty, yes? And now…” he flipped cards out of the bag onto our table; we gasped and applauded. And I reflected that the true magic of Greece is this: its ability to make strangers feel they belong, that they are among friends, even when they are very far from home. LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR MEDITERRANEAN COMFORT FOOD TOUR. SIGN UP TO RECEIVE UPDATES AS WE GO. Here's our path from Kalamata, Greece to Mytiline, Lesbos, Greece via bus and ferry. GOT IDEAS ABOUT THE TRIP? SEND US YOUR COMMENTS BELOW!

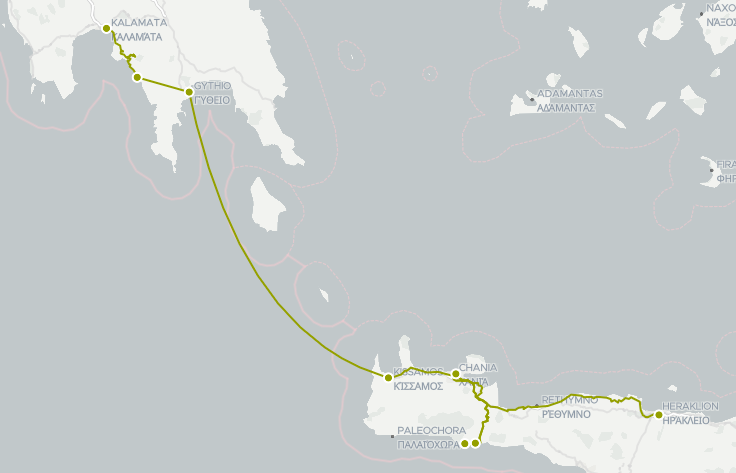

YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY “This isn’t coffee,” Rich said, glaring into his cup. “It’s gasoline.” “No, there’s definitely some coffee in it because I have grounds stuck in my teeth.” We set down the cups of revolting brew and stared around us at Kalamata, Greece: gloomy sky, empty street, silent men hunched over scattered tables under two giant trees. I could almost hear the blood from Rich’s leg wound dripping onto the paving stones underfoot. It was a low point in a day that had started with a setback and gone downhill from there. We’d awakened that morning 50 kilometers to the south in Agios Dimitrios to discover the village was in the grip of a power outage and a sirocco. Fierce, sand-laden winds that blow up from the Sahara, siroccos turn the Mediterranean sky a gritty gray and (they say) drive people mad. During the Ottoman era, if you murdered someone during a sirocco, you got a lesser sentence due to extenuating circumstances. Rich and I managed not to go berserk, even when we realized without electricity we couldn’t make coffee. The landlord of our rental apartment gave us a lift to the bus stop, conveniently located in front of the café run by Freda, widely known as the village’s most resourceful resident. She didn’t fail us now. Working with a car battery and a gas-powered burner, she produced French-press coffee for us and our friends, Jackie and Joel. Many of you know Jackie from TravelnWrite, her lively blog about expat life in Greece. After corresponding for years, we finally met IRL (in real life), and not only had she and Joel generously spent days showing us around, they came to see us off on the bus — a bright spot in the morning. “Does the sirocco always knock out the electricity?” Rich asked. “Oh no, this is a planned outage,” said Jackie. “They must be fixing something.” The outage and the sirocco extended all the way up the coast to our next stopping point, the city of Kalamata. After the picturesque charms of Crete and the rugged magnificence of the Mani Peninsula, our first glimpses — and frankly, our second and third glimpses as well — suggested that Kalamata was a soulless wasteland of shabby, crumbling concrete. We were too early to check in, so our Airbnb hosts kindly directed us to their favorite café, just around the corner under a pair of huge trees. Stepping into the deeper gloom below the branches, Rich immediately walked into a low metal table, gashing his shin. As he hobbled to a chair and began sopping up the blood with his handkerchief, I ordered coffee — the only item on offer. They were likely heating the water with kerosene, which could account for the taste. “I gotta tell you,” said Rich. “I am not warming to this town.” Disinclined to linger at the café, Rich tied his handkerchief around the wound and we set off to reconnoiter. Hours of walking took us past closed shops, lightless windows, and a few shadowy restaurants serving coffee. Suddenly Rich’s sniffer went on high alert. “Do I smell food cooking?” he said. We followed our noses into the steamy warmth of a café, where a gas cooker had produced an array of hearty dishes. In a matter of moments we were seated before heaping portions of moussaka, green beans, and chicken "mincemeat." We sighed with pleasure and tucked in. Ten minutes later the lights came on and the sun came out. Leaving the restaurant, we found ourselves surrounded by bright, inviting shops and cafés with abundant charm and originality. Our apartment turned out to be even pleasanter than it looked in the photos. Rich grudgingly agreed the town might have some redeeming features. The next morning we took a food tour, and our guide, Fotini, introduced us to local characters as well as local cuisine. Tourists are relatively rare creatures in Kalamata, and everyone seemed delighted to spend time with us. The Economakos family gave us slivers of their famous salted pork and cups of homemade wine as they showed us a picture of the sausage plate that won first prize the 1999 trade fair. We nibbled and sipped our way through the morning, shaking hands, kissing cheeks, promising to come back one day. Kalmata’s world-famous olives were mentioned only in passing, and I asked Fotini why there wasn’t more fuss about them. She shrugged. “When you’ve been eating something since ancient times, it is just a part of everyday life.” I asked if there were any special dishes we should try while we were in town. “Gourounopoula,” she said. “Roast pork with plenty of skin and fat. Back in the days of the Ottoman empire, we used it to plan a revolution. When we had feasts, we of course had to invite our Ottoman neighbors. But being Muslims, they didn’t eat pork, so when we served gourounopoula, they stayed away. And we could plan our revolution, right under their noses.” Thanks to gourounopoula — and a few other factors, of course — the Greeks gained independence in 1829 after 400 years of Ottoman occupation. Where we should try this famous pork? Fotini led me to the corner and pointed. “There. That café with the two giant trees.” “No way,” said Rich. “Oh, man up,” I said. “Let’s see if that little table is ready for a rematch.” “I want a second opinion.” When we asked at the tourist office, the woman at the desk sighed ecstatically.“Ah, gourounopoula,” she said. “Yes, you must try it. The best is here.” She pointed at the map. “At Barbayiannis.” We set off, hampered only by the fact most streets weren't marked, and the few that were didn't seem to match any of the names on our map. Eventually I noticed a window displaying the remains of a pig, with a severed head and a meat cleaver. We had found Barbayiannis! I did a doubletake. "Hey, this is the place we had lunch the first day!" What are the odds? Gourounopoula was comfort food at its finest: a crispy outer layer of roasted fat covering meat tender enough to cut with a fork. I didn’t even try to talk my way into the tiny kitchen during the lunchtime rush, but I did the next best thing and looked online for a recipe. Ideally you roast the pig whole on a spit, but when that's impractical, this video shows how to create the same effect with a pork shoulder roast and a few other simple ingredients in your home oven. “I can’t believe I’m saying this,” Rich told me. “But I actually think Kalamata is my favorite stop so far.” “You’re just saying that because you’ve stopped bleeding and have a belly full of roast pork.” “I rest my case.” LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR MEDITERRANEAN COMFORT FOOD TOUR.

SIGN UP TO RECEIVE UPDATES AS WE GO. AND SEND US YOUR COMMENTS BELOW! YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY If I’d blinked, I would have missed the snails completely. We were passing a dusty parking lot in an unfashionable section of Chania, Crete when out of the very corner of my eye I caught the flash of a yellow chair under a tree beyond the cars. Someone’s private dining spot? No, wait; turning, I saw more chairs and a scattering of tables. A battered sign said helpfully, ΠΕΡΠΕΡΑΣ. Rich and I strolled in to take a closer look. And that’s how we met Yannis, chief cook and proprietor of Perperas. He gave us a warm welcome and presented us with a handwritten English menu that was short on descriptions and long on intriguing possibilities. The meal was a delight: tzatziki made from thick Greek yogurt, garlic, and cucumber; grated zucchini patties sautéed in olive oil; a pie that might have been quiche’s Cretan cousin. Snails are everyday fare in Crete, the local equivalent of American burgers or British fish and chips. During the 40-day Lenten fast, when people are expected to refrain from eating meat, fish, even dairy, it’s OK to consume snails and shellfish; they’re exempt on the technicality of not having a backbone. It's customary to eat snails on the Thursday before Easter, and Yannis very kindly agreed to let me come into his kitchen last week, on Orthodox Holy Thursday, so I could be initiated into the mysteries of hohli bourbouristi. Brace yourself, because the process is a gruesome one. More so for the snails, obviously, but fairly distressing for humans of tender sensibilities as well. Captured when spring rain forces them out of their underground dens, the snails are sequestered in a mesh cage or simply a circle of salt, which they can’t cross because salt is lethal to snails. For at least three days, often a week or more, the captives are fed a bland diet of flour or dry pasta, which is said to make them excrete all their toxins. Then they are thrown live into a pot of boiling water which is soon covered with a white froth of snail saliva. Cookbooks advise keeping an eye out for those trying to escape so you can catch them and toss them back in. As you can imagine, the creepy backstory did nothing to enhance my appetite. “I’m calling this post ‘Snails from the Crypt,’” I whispered to Rich. Fortunately I was spared the grim necessity of witnessing these atrocities in the flesh. Yannis explained a family of snail collectors in the nearby village handled all that, delivering the snails to his kitchen clean and ready to cook. Yannis rinsed 30 large snails in water, then dusted them with a third of a cup of flour. (He never measured, so all quantities are very approximate.) Then he poured a quarter of a cup of olive oil into a frying pan and set it on the burner. He pressed the fleshy foot of each snail into salt then set it in the pan. “They go in ‘face down,’ as we say,” he told me. “The name bourbouristi comes from the Cretan abouboura, which means ‘face down.’” When the snails were sizzling, he pulled leaves off of two sprigs fresh rosemary and sprinkled them on top, adding a pinch of pepper. Pouring half a cup of strong red wine vinegar over everything, he let it cook for about three minutes until the liquid reduced to a thick sauce. "Done!" he said. He took them outside to our table and set them down with a flourish. It was love at first bite. “Oh my God,” I kept gasping. “Wow!” Using the outermost tine of his fork to pry out a morsel, Rich slurped it down. He kissed the shell he held his fingers. “These snails,” he said, “were not sacrificed in vain.” Lenten observances in Greece are big on sacrifice, starting with 40 days of fasting and culminating on the eve of Easter when Judas Iscariot, the apostle who betrayed Jesus, is burned in effigy in towns all across the island. We witnessed the ritual in Loutro, a village on the southern coast of Crete. The evening began with the traditional Orthodox liturgy held in a church so small people took turns going inside to pay their respects then gathered outside chatting quietly. Eventually the priest emerged and sang into a microphone held by an altar boy, reading the lyrics off a cell phone tucked into a hymnal. Men and boys took turns ringing the church bell. After the kiss of peace, everyone lit their candles; some kids carried fancy ones decorated with unicorns, Barbie, or Spiderman. Then the bonfire was ablaze on the beach, and altar boys, bell ringers, and Spiderman fans began throwing fire crackers into the blaze, making everyone jump. As flames consumed the effigy, fireworks exploded overhead. Once again, sin had been vanquished. Easter Sunday was a quieter affair as families released from fasting gathered to feast on lamb, the traditional symbol of sacrifice and salvation. In Greece, the practice of animal sacrifice dates back to Neolithic times; more recently it appears as the Passover lamb, first offered during the Israelites' Exodus from Egypt, and in New Testament passages where John the Baptist refers to his cousin as “Jesus, the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world.” For us, more prosaically, lamb was simply lunch. For this meal, Rich and I had chosen a family-run restaurant on the hill just above the church, and during the morning we dropped by to see how the roasting was coming along. The lamb was turning slowly on the spit, looking all too much like a human sacrifice. There was aluminum foil draped over its loins, like the white cloths strategically placed on naked figures in old church art. “Boy, these guys really know how to work a theme,” I said to Rich. The snails, bonfire, and lamb of Easter — as well as the island of Crete itself — are now just fond memories. Yesterday we took a ferry north to Greece's Mani Peninsula, a rural area on the southern tip of the Peloponnese. Our modest hotel overlooks the island of Gytheio, where Paris of Troy and Helen of Sparta spent their first night together, having the sex that launched a thousand ships, culminating in the Trojan War. Rich and I don't expect our further adventures in Greece to be quite that exciting, but we are looking forward to more good food and fun times. Stay with us on the journey! LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR MEDITERRANEAN COMFORT FOOD TOUR.

SIGN UP TO RECEIVE UPDATES AS WE GO. AND SEND US YOUR COMMENTS BELOW! YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|