|

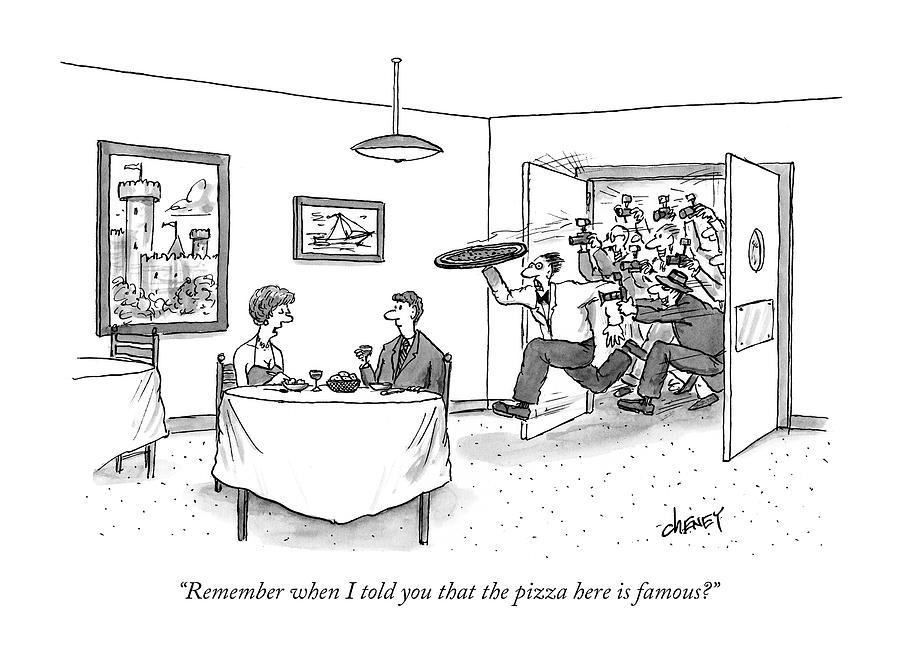

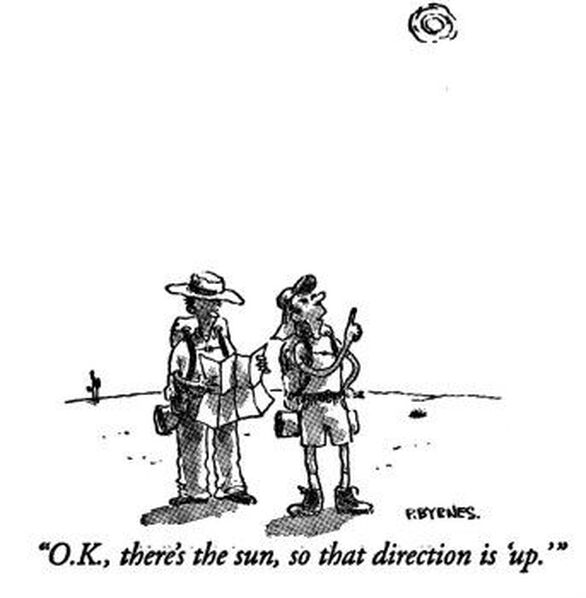

You have to love the impish sense of humor that prompts a train station to fill its waiting room with sturdy wooden benches then labels them, “NON SEDERTI QUI (PLEASE DON’T SIT HERE).” As if any further taunting were needed, this train station — and, coincidentally Rich and I — stood at the base of a mountain that was 3054 feet high and famously difficult to ascend. Naturally the area was utterly devoid of taxis or buses. I could almost feel the mountain chuckling deep in its interior. Its sheer cliffs had defeated countless would-be invaders from the 14th century BC until the invention of artillery and aerial warfare. Had Rich and I met our match? “I am not walking up the mountain,” I mentioned to Rich casually but emphatically, recalling last week’s adventure involving a grueling hike that ended with shimmying through a chain link fence. “Don’t worry. We’ll find a ride,” he said, fiddling with his phone, which inexplicably refused to function. Eventually we joined forces with the two other stranded passengers milling about the station. A cab was summoned, and we drove up to Enna, the highest and most central point of Sicily, affectionately known as its umbelico (belly button). Speaking of bellies, mine was growling to remind me I’d given it nothing but a cookie for lunch on the train. Sadly my hopes of immediate food acquisition were quickly dashed. “Here we eat at eight o’clock, not before, never before,” said my hostess at the cozy B&B in the center of town. I groaned inwardly. It wasn’t even 5 pm yet. “Here are the best restaurants.” She gestured towards business cards in neat stacks on a table. I grabbed a handful, and Rich and I went out to explore the town. We strolled about, enjoying the impressive baroque buildings, the charming old stone houses, the cobbled streets, and the general atmosphere of tidiness and friendliness. Wandering into the Church of St. Claire, I found a sign demanding SILENCE and a docent who spent the next twenty minutes chattering nonstop in Italian. I managed to grasp that this was a shrine to those who died in WWII as a result of bombing by the Allies. Our guys. It was a rather lowering feeling, and I had to resist the impulse to apologize. Emerging into the twilight, Rich and I happened upon one of our hostess’s recommended restaurants, but it was a pizza place so we continued on in search of heartier fare. We hit another of the recommended places. Pizza again. We passed another and another, all pizza parlors. Eventually we found a charming, old-fashioned trattoria with dim lighting and white table cloths. I opened the menu. “Nothing but pizza?!?” I exclaimed. “Where are we — in the Twilight Zone?” An English-speaking waiter took pity and directed me to an eatery offering fish, meat, even (gasp!) vegetables, so in the end we dined well. The next morning at breakfast our hostess told me there was a food festival in the main square. I made a beeline for it. “Are you kidding me?” I exclaimed on arrival. “A pizza competition? Really?” Local chefs were busy pulling pies out of ovens, judges were nibbling, frowning importantly, and pronouncing opinions, and members of the crowd, presumably cronies and bigwigs, were happily receiving the leftover slices. Somehow Rich managed to sneak a hand in and snag one. It was the best pizza I’d ever tasted. The slim, delicate crust was lightly brushed with olive oil and hint of local cheese topped with a sliver of prosciutto and fresh herbs. “Maybe this town is onto something,” I said. I don’t need to tell you pizza is popular. Americans are the world champions, consuming a hefty 28.6 pounds per person per year, with the average Italian downing 17 pounds, about twice as much as other Europeans. By my calculation, Enna’s residents consume their own body weight in pizza every month. I wondered why it was so extraordinarily popular here. Was it a natural outgrowth of Sicily’s long association with Naples, which created modern pizza in the 18th century? Or did the roots go back much, much further? By 400 BC, Enna was the site of the most important sanctuary of the fertility goddess Ceres, who gave us agriculture (and hey, thanks for that, ma’am!) as well as the word “cereal.” Later generations came to know her as Demeter, mother of Persephone, who was abducted by Pluto. No, not Mickey Mouse’s dog, I mean the god of the underworld, aka Hades. Ceres’ ancient temple no longer exists, but her story lives on in Enna’s Museum of Myth, the first entirely multi-media museum in Italy. According to legend, Persephone was carried off from Enna itself, or possibly from the shore of nearby Lake Pergusa. Enraged, Ceres went searching for her daughter in a chariot drawn by snakes. Inexplicably, this detail was left out of the museum’s presentation (possibly due to truth issues). Without Ceres around to oversee the earth’s fertility, the land was devastated; onscreen, the images shifted from waving wheat to scorched earth, interspersed with scenes of hell, which apparently looks like this. Humans begged other gods for help, and eventually Pluto/Hades was persuaded to let Persephone return to the earth’s surface. But he craftily got her to eat six pomegranate seeds to fortify herself for the journey, condemning her to spend six months a year with him. And that’s why we have the seasons. I think it all made a bit more sense a few thousand years ago. My point is that Ceres was pretty hot stuff around Enna for a long time, which suggests one possible explanation for the obsession with grain-based foods. Or maybe it’s just that the residents know a good thing when they taste it. The Museum of Myth, the Rock of Ceres, and the city’s castle occupy the highest, most impregnable part of the mountain. Looking out from the castle tower, you can understand how the original Sicani held it for 1000 years. When attacked, all you’d have to do is stand at the edge and drop rocks; when technology improved, you’d shoot arrows or pour a little boiling oil. Frankly, I don’t know how any invader even got that far. I would imagine that the few soldiers who didn’t die of cardiac arrest or pass out from the heat on the way up sensibly opted to slip away among the trees to wait quietly for events sort themselves out rather than do any serious storming. Throughout its long history, Enna was usually lost through treachery rather than battle. The first to take the castle by force were the Romans, who snuck in through the sewers. You can imagine the pep talk. “Guys, we’re going in at night. It’ll be cooler and no one will see us, so none of those pesky arrows or boiling oil. On the downside…” Enna may not be the easiest place to get to, but it’s worth the effort. If only so you can brag about visiting Sicily’s belly button — and of course, eat some of their legendary pizza. JUST JOINING US? THE NUTTERS' WORLD TOUR SO FAR RIGHT NOW: SICILY Agrigento: "The Devil Made Me Write It!" Palermo: The Good, the Bad & the Nutty SUMMER 2023: CALIFORNIA SPRING 2023: SPAIN WANT TO STAY IN THE LOOP? Subscribe to receive notices when I publish my weekly posts. Just send me an email and I'll take it from there. [email protected] And check out my best selling travel memoirs & guide books here. PLANNING A TRIP? Enter any destination or topic, such as packing light or road food, in the search box below. If I've written about it, you'll find it.

3 Comments

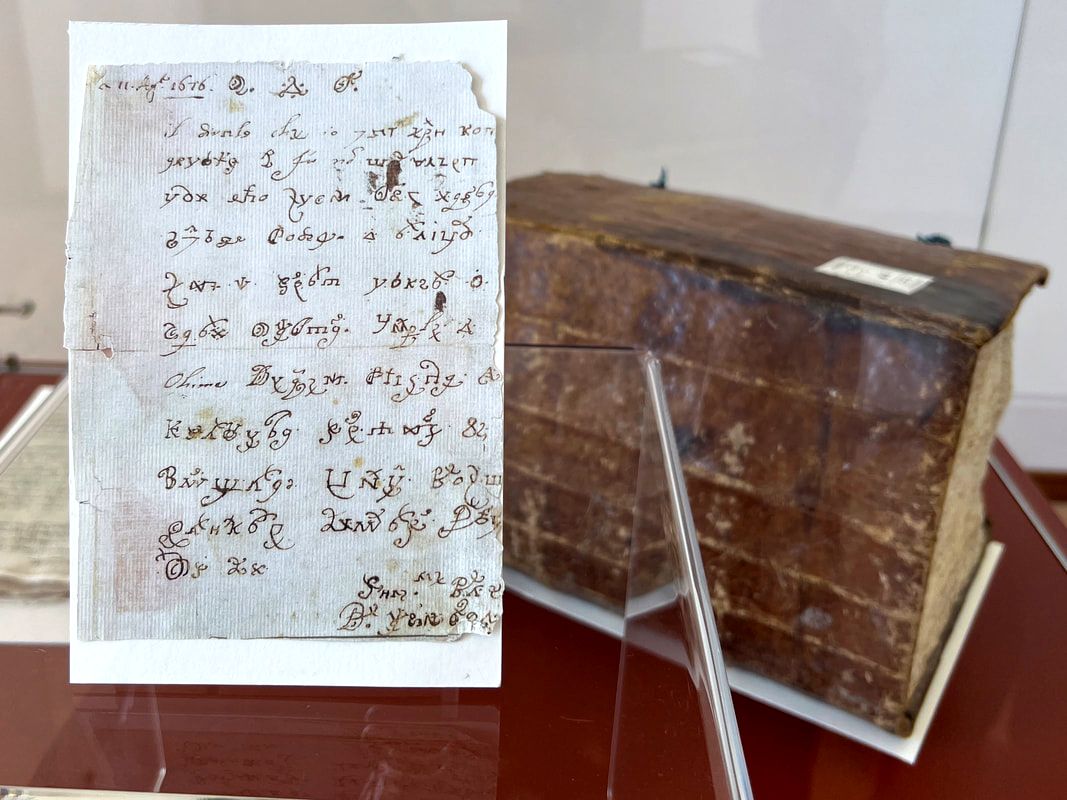

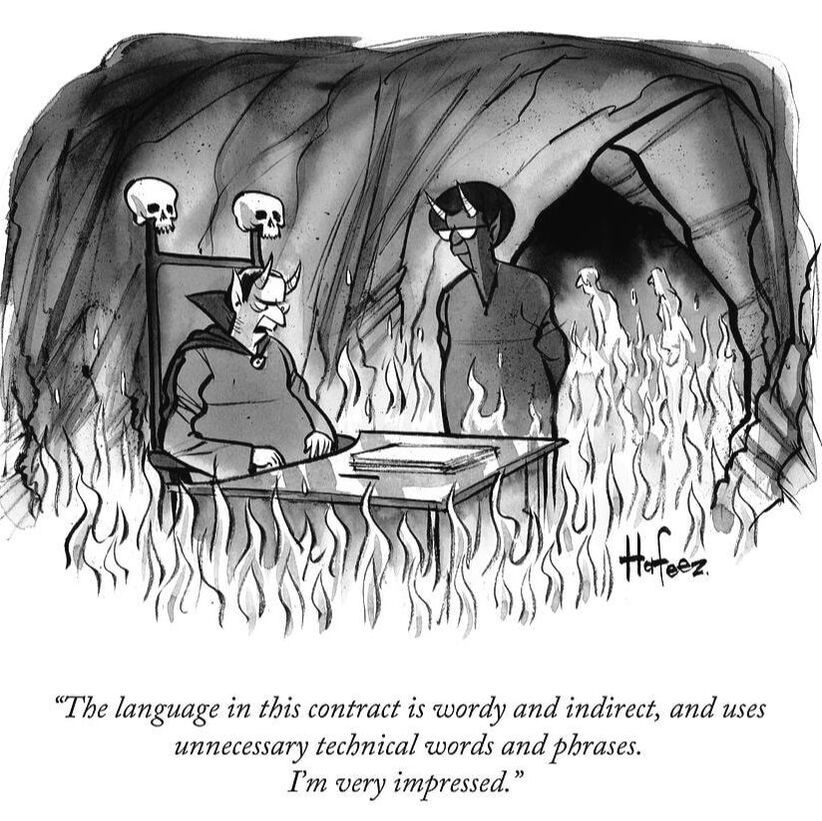

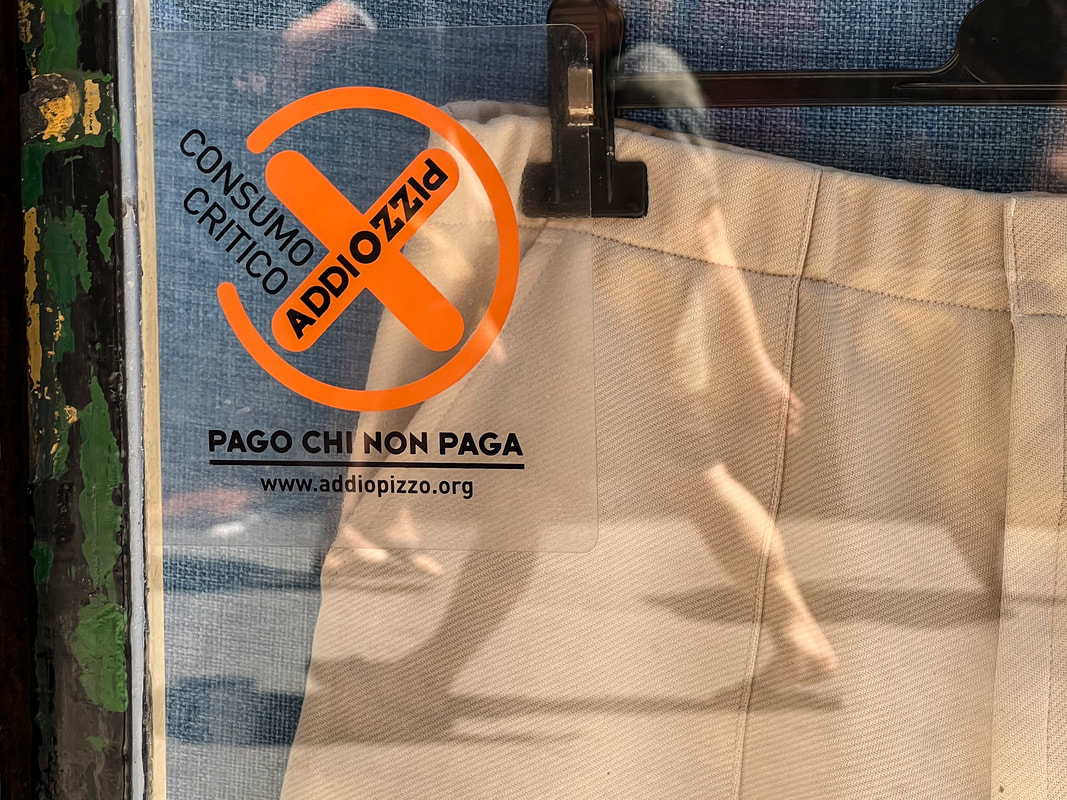

Was the letter in the photo above actually composed by Satan? It was discovered in 1676, clutched in the hand of Sister Maria Crocifissa della Concezione (Sister Mary Crucified of the Conception), as she lay collapsed on the floor of her Sicilian convent, covered in ink and gibbering incoherently. As anyone would be, after spending the night fending off the Devil’s advances. When she could talk, Sister Maria Crocifissa said Beelzebub forced her to write the letter, composed of strange characters and symbols, in an unsuccessful attempt to persuade her to abandon her faith and follow him. Naysaying cynics suggest Sister Maria Crocifissa might have been schizophrenic. But the Church took her seriously, launching a 100-year study of the incident that ended in nominating her for sainthood. Her body remains in the convent chapel, an object of veneration, but the letter is kept in the cathedral of Agrigento, where Rich and I are now. Yes, of course I made a beeline to see it. Sadly, the original is stored in the archives, so I could only view the copy. But still! Scholars struggled for centuries to decipher the bizarre document, but it remained a mystery until 2017. That's when Sicilian scientists announced they’d translated the letter using a military codebreaking algorithm they found on the Dark Web (so obviously totally legit and reliable). They said the letter was composed of scrambled Latin, ancient Greek, Arabic, and Runic alphabets, all languages the nun knew from her work as a linguist. The text attacked Christianity, saying God was invented by man. It described God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit as “dead weights” and said, “This system works for no one.” Sister Maria Crocifissa rejected the message and the messenger, causing Satan to depart howling with frustration. And although I am rarely one to have sympathy for the Devil, I must confess I have frequently felt very similar sentiments here in Agrigento. This ancient, once-powerful town on Sicily’s southern coast looks charming and has great stuff to see and do, but it is mind-bogglingly difficult to navigate. There’s practically no dependable information available on anything, starting with the location of tourist information offices, which appear on maps but nowhere else. Supermarkets have proven equally elusive. Our first afternoon in town, GPS led us out of the old center into increasingly dubious and deserted neighborhoods. As the sky began to darken, we were surrounded by scattered garbage and feral cats and decided we didn’t need provisions that badly. Later, I learned all the supermarkets and greengrocers had fled to the suburbs. In the center, a few tiny mini-marts are the only option. How I miss Palermo’s farmers markets! What’s truly staggering is how difficult it is to visit Agrigento’s main claim to fame: The Valley of the Temples. This is the largest archeological park in Europe, visited by somewhere around a million people a year (nobody has verifiable numbers, of course). The centerpiece, the Temple of Concordia, is one of the best-preserved ancient Greek temples on the planet; it impressed UNESCO so much they based their logo it. The Valley of Temples is considered a must-see for anyone visiting Sicily. But they sure don’t make it easy to get there. The site is just two miles from the city, and yes, there is a shuttle, but the bus stop is so shabby and poorly marked we kept bypassing it during our search. When we finally realized we were looking right at it, we discovered there was no schedule posted at the bus stop — or online either. Foreign visitors milled aimlessly about in the stunning heat, frowning at their phones in bewilderment. When the bus finally arrived and we were on our way, I said to Rich, “What is it about withholding information in this town? Some form of omerta? If we tell you, we’ll have to kill you?” The Valley of the Temples was truly spectacular. Of course, it isn’t really a valley but a ridge; the Greeks loved to place their temples high on windy outcroppings. Why? “Think about the air passing through these columns. Think of it like a wind instrument,” says architect and travel writer Sarah Murdoch. “As the air passes through these columns, it would produce vibrations that you can’t hear. But the Greeks had the idea that the vibration, once it passed over the Greek city, would create a sense of peace and harmony amongst the people.” Wow, can we bring that architectural concept back now? After tramping across the site for hours under the sweltering sun, Rich and I weren’t thrilled by the prospect of the long walk back to the entrance followed by a wait of indeterminate length for the shuttle to the archeological museum. Consulting his GPS Rich announced, “I can get us there another way. There’s a path.” “Is this going to be like the hunt for the supermarket?” I asked skeptically. “Of course not.” I could see the path and the archeological museum a mile away. “Won’t there be a fence? I am not climbing a fence.” “Of course not.” “If there is a fence at the end of this long, hot walk, I am sitting down until you return with bolt cutters.” “It won’t come to that.” It very nearly did. We trudged alone through olive groves, the sun breathing down the back of my neck like a dragon. After a small eternity, we found ourselves close to the archaeological museum and — you guessed it — our way was blocked by a high chain-link fence. Eventually we discovered the fence had a small gap, maybe ten inches wide, where others had slipped in and out. “Perfect!” cried Rich enthusiastically. He began wriggling through to find himself standing on top of a six-foot wall. “No problem!” He shinnied down using parts of the adjacent gate for footholds. “Now you!” I can never decide whether squirming through that gap was the best or worst moment of the day. I kept expecting to hear my trousers ripping as I fell to my death, or at least to a broken ankle. When I made it safely to solid ground, I knew I’d feel tremendously euphoric if I ever managed to catch my breath again. I’ll say this for Agrigento: it keeps you on your toes. Even our apartment has its challenges. Airbnb never mentioned this apartment has four different levels joined by smooth marble stairs completely lacking in handrails. I don't dare risk wearing my slippers on them. If I get up in the night, I have to put on my sure-grip sneakers, my eyeglasses, and all the lights, turning what's normally a quick trip into a major production. Yes, here in Agrigento, I am really living on the edge. My life is all about survival now. I can’t buy healthy groceries. The stairs in my apartment are a fatal accident waiting to happen. I'm in a constant state of ignorance and bewilderment. But I am heartened to discover that I can still sneak through a fence without getting caught, something I haven’t undertaken in decades. Who says travel doesn't keep you young? JUST JOINING US? THE NUTTERS' WORLD TOUR SO FAR RIGHT NOW: SICILY Palermo: The Good, the Bad & the Nutty SUMMER 2023: CALIFORNIA SPRING 2023: SPAIN WANT TO STAY IN THE LOOP? Subscribe to receive notices when I publish my weekly posts. Just send me an email and I'll take it from there. [email protected] And check out my best selling travel memoirs & guide books here. PLANNING A TRIP? Enter any destination or topic, such as packing light or road food, in the search box below. If I've written about it, you'll find it. On our first morning in Palermo, Sicily, Rich bounded out of bed with the unbridled joy of a man who knows he’s having ice cream for breakfast. I’d read about the Sicilian tradition of starting the day with scoops of gelato stuffed into brioche, and as Rich kept pointing out, I owed it to my readers to dig deep into this subject. We found a café and tried to place our order. “Brioche con gelato? Now? Well, yes, you could,” said the proprietor, in the dubious tones of one who acknowledges that yes, you could wear pink to Don Corleone’s funeral, but are you sure you want to? “It’s not for breakfast?” I asked incredulously. How did I get this so wrong? “When is it eaten? Later in the morning?” “Yes. Morning, lunch, afternoon. Any time.” Except, apparently, now. We ordered croissants instead. This was my first hint of just how slippery I’d find Sicily’s culinary traditions. Palermo is famous for its street food, which is sold in carts and hole-in-the-wall eateries all over town, and I soon learned what people really prefer for breakfast is pani ca' meusa (in proper Italian, pane con la milza). To make milza, you boil up cow spleen, lung, and trachea, fry them in pig lard, and tuck them into a bun, possibly sprinkling cheese on top. Everyone assures me this meal will give you the strength to get up and do what needs to be done. Did I try it? Oh, hell, no. There are some things at which even I draw the line. But those raised here love this kind of stuff. Frequently conquered and perpetually impoverished, Sicily has spent centuries getting creative with obscure animal parts. Whenever I see gusts of smoke rising from a grill, I know it’s stigghiola, lamb or goat guts rolled around a skewer or leek and cooked over the flames. Another common sight is a large, cloth-covered basket known as a panaru, inside of which is frittola. Nobody seems to know exactly what ingredients make up frittola, but the prevailing theory is cartilage, lard, and some kind of meat. Street vendors dip their hand under the cloth, extract a greasy blob, drop it onto oiled paper, and pass it over to you. Mmmmm. I’ve had ample opportunity to observe all this as our Airbnb apartment is in the heart of Capo, one of the city’s largest street markets, built a thousand years ago to serve the new Arab overlords. Since then it has been a favorite with everyone from families to princes to pirates and has sustained generations of pickpockets. These days Capo has reinvented itself as “a bustling agri-food trading hub,” catering to tourists as well as locals. There’s constant hubbub. Vendors shout out their wares, delivery boys whistle and sing, bands play, fireworks explode (mostly at night, but on Sunday at 9 am) (nope, no idea why), weddings are celebrated, religious statues are carried through, and astonishing amounts of fresh produce and street food change hands. I love the sprawling, shouting, chaotic vitality, and so did Sicily’s renowned artist Renato Guttuso. He painted another old Palermo street market La Vucciria so vividly that it is now among the most beloved works of art on the island. I was determined to see Guttuso’s painting, now displayed in the 14th century Steri Palace. We went there the first morning, right after our croissants, and I was slightly dismayed to discover viewing the painting could only be done in the context of a gruesome guided tour of an Inquisition prison. The building housing the prison, the painting, and a few other random artifacts started out as home to Palermo’s nobility; 200 years later it was surrendered to the Spanish when they became Sicily’s newest overlords. As this happened during the Inquisition, the palace was soon filled with prisoners who created elaborate graffiti using scrapings from terra cotta floor tiles and their own bodily fluids. (You do not want to know the details.) Eventually everyone in those cells was executed in the palace’s front garden, on the spot now occupied by the Strangler Tree, said to have grown to its enormous proportion thanks to all the blood soaked into the soil. Yes, eventually I saw Guttuso’s painting, which was marvelous, but emerging into the sunlight of late morning, I realized the grisly tour had left me a bit demoralized. Rich said he knew just what I needed to recombobulate: brioche con gelato. Apparently it's typically eaten as a second breakfast. The day proved typical of our time here in Palermo: the delightful, the delicious, and the deeply disturbing all jostling for attention. On the positive side I reconnected with a bookseller I’d met during a brief visit here in 2016. Retired accountant Pietro Tramonte presides over the Biblioteca Privata Itinerante (Private Traveling Library), a warren of 75,000 books in a back alley near the marina. For those who love to read, he says, “the paper material is like cheese on macaroni.” I showed him the photo of us from seven years ago, and he was delighted, posing for more pictures and then taking us out for coffee. Another wonderful experience was lunch with a Palermo couple in their home, arranged through EatWith. Piera and her husband Rino gave us a warm welcome and platters of scrumptious food. Soon all four of us were talking at once, waving our hands around for emphasis, and laughing together like vecchi amici (old friends). Inevitably, talk turned to one of the island’s most famous exports: the mafia. “More dangerous than ever,” said Rino. “They do not affect our days, our lives directly, but they are deep inside industry and government.” I’d heard about the anti-mafia movement, started in 2004, that included local businesses placing a sticker on their window to indicate their refusal to pay “pizzo,” extortion money. So far I have only seen one such sticker, and I can only assume everyone else who posted them now sleeps with the fishes. To be fair, Palermo’s blood-curdling side was evident long before the mafia, as witnessed by the Cappuchin Catecombs. Here we found 8000 dead bodies hanging from the walls, hooks in their backs and a wire around their chest to keep them from toppling forward onto us. Many appeared to be screaming. Frankly, it was all I could do not to scream myself. The oldest were 17th century monks, some wearing heavy ropes of penance around their necks. In the 19th century it became fashionable for prosperous citizens to pay the Capuchins to place deceased relatives in the catacombs. Families would visit, dust the corpse, and replace any clothing that had rotted. They had to keep paying the Capuchins, and if they fell behind, the bodies would be removed and set aside until the account was paid up in full. “Sicily is a Nutters’ paradise,” a friend wrote to me some months ago, and boy, was she right. Palermo is eccentric, rich in history, and quirky in nature. I just love this ancient city. But in a few days, we’re off to another part of the island where, among other things, they claim to have an actual letter written by the Devil himself. More on that next week. JUST JOINING US? THE NUTTERS' WORLD TOUR SO FAR SUMMER 2023: CALIFORNIA SPRING 2023: SPAIN WANT TO STAY IN THE LOOP? Subscribe to receive notices when I publish my weekly posts. Just send me an email and I'll take it from there. [email protected] And check out my best selling travel memoirs & guide books here. PLANNING A TRIP? Enter any destination or topic, such as packing light or road food, in the search box below. If I've written about it, you'll find it. |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|