|

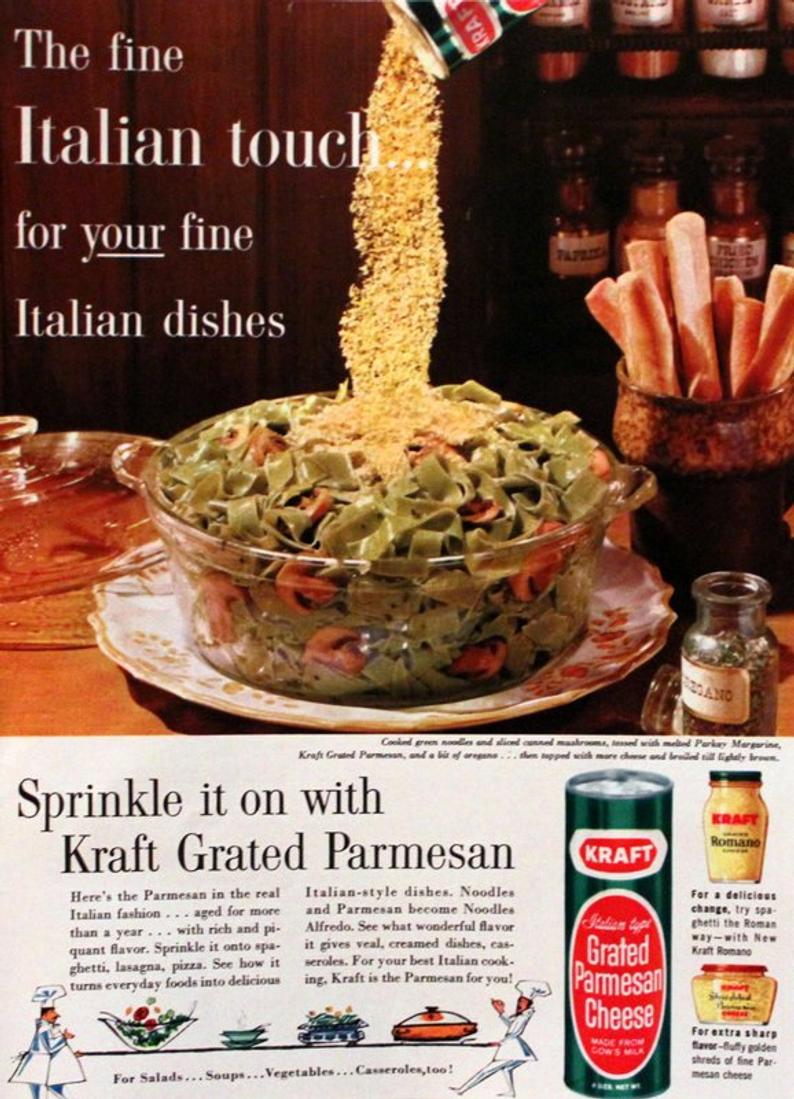

Hosting dinner parties in a foreign country provides abundant opportunities for pitfalls, pratfalls, and faux pas. I often recall with a shudder one particular night, shortly after we moved to Seville, when I passed around a cheese platter only to have my Spanish guests throw back their heads and howl with laughter. I stared at the platter, which contained an apparently innocent collection of Manchego and cheddar, crackers, and one of the cheese knives that came with the cutting board I’d bought the day before. The farmer next to me was among the first to recover his equanimity, and as he sat wiping his eyes with a cocktail napkin, I asked what the fuss was all about. “This,” he said, holding up my new cheese knife, “is what we use for castrating the pigs.” And off he went into even greater paroxysms of merriment. I offered to fetch another knife, but my guests wouldn’t hear of it, chortling softly and exchanging amused glances every time they passed the platter. Needless to say, that knife was retired to the back of the drawer, never to be seen again. Until last Wednesday evening, when its twin showed up in the hand of my hostess at a dinner in Parma, Italy. This, I soon learned, was a tagliagrana, whose drop-shaped blade is perfectly designed to break hard cheeses into shards — ideal for serving the region’s most famous product, Parmigiano-Reggiano. Having grown up shaking pre-grated parmesan out of a green tube, I had never seen anyone use a tagliagrana. As an adult I’ve had plenty of genuine Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese in stuff and on stuff, but I’d never thought of it as a stand-alone appetizer. So it wasn’t until Wednesday’s dinner — when my hostess, Stefania, cut off small chunks and drizzled them with her homemade balsamic vinegar — that I realized what I’d been missing. Parmigiano-Reggiano, “the king of cheeses,” is the pride of Parma, the neighboring city of Reggio Emilia, and the surrounding region of northern Italy. European law protects the name and strictly defines the region where it can legitimately be produced. Other areas of the world (yes, USA, I’m thinking of you) aren’t bound by these laws, and they can — and do —call just about anything “parmesan.” Production and quality vary wildly, and cheap cheddar, Swiss, or mozzarella are often added for bulk. A scandal erupted a few years ago when authorities finally noticed that Castle Cheese and others major producers were adding hefty amounts of cellulose — that’s powdered wood pulp, in plain English — to their so-called parmesan. That’s not the way to add fiber to your diet! Over dinner, Stefania described how true Parmigiano-Reggiano is produced, a process that has remained essentially unchanged for more than 800 years. There are only three ingredients: milk from cows raised in the designated region on local fodder, salt, and calf rennet (a natural bovine enzyme that helps curds form). The milk must be used fresh, within hours of milking. Cheese is produced in 37-kilo (81.5-pound) wheels that are soaked in a salt bath to aid preservation, then stacked in aging rooms for one to three years. “But you and Rich should see this for yourselves,” Stefania said. As it happened she was taking house guests to a local cheese producer called Consorzio Produttori Latte the very next morning. It didn’t take much persuasion to get us to join the party. After the tour, we stopped in a small village to see Stefania’s country home and sample more of her homemade balsamic vinegar, which is aging gracefully in the airy attic in the customary manner. Italian law protects the most famous labels such as Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena (Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of Modena), enforcing such restrictions as age (at least 12 years) and additives (none). You probably won’t be surprised to learn that American brands labeled “balsamic vinegar,” even those specifying “barrel aged in Modena, Italy,” are often juvenile liquids containing corn syrup, guar gum, and/or worse. Stefania’s nine-year-old vinegar-in-training was an explosion of brash flavor in the mouth, where the 21-year-old vintage was nearly as thick, dark, and tangy-sweet as molasses. The real highlight of our time with Stefania was dinner in her Parma home. After the Parmigiano-Reggiano, we enjoyed the famous Prosciutto di Parma, cured ham sliced so thin you could see through it, with flavor slightly sweeter and less salty than prosciutto from other regions. Dinner included local tomatoes, eggplant, and borettana onions, a squat, sweet variety that’s been grown in the nearby town of Boretto since the 15th century. There was creamy veal scallopini in lemon sauce. But the absolute star of the show was the succulent Coniglio alla Cacciatora (Hunter-style Rabbit). [See recipe for Coniglio alla Cacciatora (Hunter-style Rabbit).] Rabbit is popular on dinner tables in Seville, too. When I first moved there, I was horrified to see the furry bodies of lifeless bunnies hanging by their paws in the local butcher shops. When I asked a friend why they didn’t prepare them for sale in the ordinary way, skinned and trimmed, she explained the custom dated back to the Hunger, the lean years after the Spanish Civil War when nobody had enough to eat. “It’s so you know it’s not cat,” she told me. Enough said. I’ve vowed to learn to cook rabbit someday, and now that I have Stefania’s recipe, I’m ready to give it a try. Those of you who can’t warm to the idea of rabbit for supper will be happy to hear the recipe works just as well with chicken. (Or you can make it with rabbit and tell the kids it’s chicken.) Whatever you bring to the table, be sure to preface the meal with a few chunks of genuine Parmigiano-Reggiano, chopped with a tagliagrana — which with any luck at all, your friends and family won’t associate with anything but the pleasures of perfectly delicious cheese at a homemade Italian dinner. Unlike some of my better-organized and more practical blogger friends, I never accept free goods or services in return for promoting anything on this blog. Everything I write about is included solely because I believe you might find it interesting and useful for planning your own adventures. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY Our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour Continues!

Don't miss a single loony adventure or mouthwatering recipe. Sign up to receive updates.

19 Comments

Remember the chicken dance? The one where you flap your wings and shake your tail feathers? When was the last time you did it walking down the street in a foreign city? Yeah, I can’t remember either; maybe never — until last Monday night in Zagreb, Croatia. That’s when Rich and I heard the chicken dance song coming from the bandstand in Zrinjevac Park and found it too infectious to resist. Fortunately for what remains of my dignity, we weren’t the only ones flapping wings and shaking tail feathers down the sidewalk, under the amused gazes of passing drivers and fellow pedestrians. We hurried toward the bandstand, coming to roost just as the tune ended. No matter. There’s music every night this week and next, mostly foot-taping golden oldies like the Drifters’ “Under the Boardwalk” and I-love-this-one heartwarmers like Louis Armstrong’s What a Wonderful World. The first time we went, Rich and I settled at one of the tiny wooden tables placed around the bandstand and looked around at the small crowd. On a nearby lawn, kids were chasing each other through the twilight, jugglers were practicing under the trees, and women on park benches were languidly cooling their faces with paper fans. Beneath the lights strung in the branches overhead, people were dancing. And pretty soon, we were too. “It feels like Hometown, USA,” I said to Rich. “It’s like the best part of every summer I can remember.” That nostalgia was precisely what city officials were trying to spark when they started the Zagreb Time Machine project, which for many years has sponsored summer dances, street theater, and other public entertainments designed to “bring the romantic spirit of past times to life.” I’d somehow missed all the other activities but fell instantly in love with the Dance Evenings. Zagreb’s Time Machine is set to the mid-20th century, but local history dates back a great deal farther than that. The city was founded in Roman times, expanded during the medieval and industrial eras, survived Nazi occupation, became an economic powerhouse in the former Yugoslavia, and today serves as the capital of independent Croatia — to mention but a few highlights. Through all the changes, one thing has proved constant: this is a city that loves its comfort food. When Rich and I reconnected with Lidija and Mladen, Croatian friends we’d met during an EatWith dinner during our 2016 visit to the city, we told them about our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. They instantly responded with a flood of suggestions about what we should be eating while we’re in town. "Strukli, of course," Lidija mused aloud. "And mlinci. Have you tried deer goulash? The best place to find such dishes is Zagorje." Setting off in Mladen's car, we soon found ourselves on the winding roads of Zagorje, a rural area north of Zagreb that needed no government-funded entertainments to give the impression we'd traveled backward in time. Around each curve we discovered families raising cows, grapes, and corn on small farms in sleepy valleys presided over by Medieval castles. “This was the center of the Peasant Revolution of 1573. It all started right here,” Lidija told me. “The nobility demanded that each family contribute food to them. People were living on the edge of hunger, but the lord had an army, and they had to pay. Like today we are forced to pay taxes. So the peasants staged a revolt. It lasted only 12 days. And they took the leader of the rebellion, Matija Gubec, and said to him, ‘You wanted to be king. Here is your crown.’ And they put upon his head an iron crown that was heated red-hot in the fire.” Yikes! “And then they tore him into four pieces.” Quadruple yikes! Gubec became a folk hero, inspiring various political movements, the first Croatian rock opera, and Josip Broz Tito, who was born in a humble Zagorje farmhouse and went on to become president of Yugoslavia. As you can imagine, Zagorje’s cuisine is designed to fortify hard-working agricultural families attempting to subsist on what’s left after the powerful have taken the lion’s share of everything produced on the land. Traditional fare is hearty, made from fresh, inexpensive local ingredients, and bristling with the fats and carbs you’d need for long hours of physical labor. Not exactly health food, but it is a glorious indulgence you’ll never regret. “Here we will eat štrukli,” said Lidija, pulling up at a 1938 country inn called Villa Zelenjak Ventek. When the staff learned this was to be our first tasting of štrukli, Dora, a young, English-speaking manager, arrived to tell us about the treat in store. It seems you make a basic dough, roll it so thin that it completely covers the tabletop, stuff it with a mix of cottage cheese, eggs, sour cream, and salt, and bake it into a sort of cheese strudel. Dora kindly shared photos and the recipe, so that I could pass the legendary dish on to my readers. [See štrukli recipe and photos here.] After lunch, we worked off a few calories strolling around Kumrovec, a charming village of restored nineteenth-century homes centered around Tito’s birthplace and a museum honoring his legacy. While many regarded him as a ruthless dictator, others look back with what’s now known as “Yugonostalgia,” fond memories of simpler times when everyone had a job, a place to live, and enough to eat. “Were you better off then?” I asked Lidija. “In many ways, yes,” she said, with a philosophical shrug. “Things are much harder for us now.” Our final stop of the day was Gresna Gorica, a rustic restaurant nestled in vineyards below the fairytale towers of Veliki Tabor castle. Sitting outside among the vines, we sampled lard laced with bacon, cottage cheese topped with crème fraiche, deer goulash, beans drizzled with pumpkin seed oil, and duck served over something called mlinci, a mysterious dish that appeared to be pasta but inexplicably wasn’t. I may have been a bit muddled by the staggering heat and the natural exhaustion following a day’s vigorous sightseeing, but I simply couldn’t seem to grasp Lidija’s explanation of how mlinci is prepared. It’s a kind of bread and you boil it? Really? “Come to my house and I will make it for you,” Lidija said. “Then you will see how it works.” How good was it? It was so yummy Rich and I started doing the chicken dance right there at the dinner table. Luckily our Croatian friends were familiar with this silly tradition, so they didn’t think we were completely insane. (Or if they did, they were too polite to say so.) We all stuffed ourselves and then sat for a long time, blissfully picking over the remains of the mlinci. [Get mlinci recipe here.] “One thing is clear,” I said to Rich said on the way home. “If we’re going to keep eating like this, we’re going to have to do the chicken dance a lot more often.” Rich just made happy clucking sounds and kept on walking. See all posts about the Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. See all recipes and videos. Don't miss a single loony adventure or the next mouthwatering recipe. Sign up below for updates. Thanks for joining us on the journey.

“Bey’s Soup is the ultimate comfort food of the Balkans,” Dalida told me, as she began chopping onions. “We eat it in every season, at the holidays, for special occasions — all the time really.” “Who is Bey?” I asked. “Ah, that would be Gazi Hüsrev Bey,” she said, smiling the way you do when someone mentions your absolutely most favorite uncle. “Bey was his title; it means governor. Gazi Hüsrev Bey was the great benefactor of Sarajevo.” You can’t spend more than a few hours in Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, without hearing about this man. His name is still, respectfully, on the tip of every tongue — which is not bad considering he lived 500 years ago, in the dark ages before social media. Hüsrev came from money and power, grandson to one sultan, and after a string of successes on the battlefield, chosen by another — Suleiman the Magnificent — to govern Bosnia for the Ottoman Empire. As fans of Game of Thrones know only too well, wealthy titled grandsons and war heroes don’t always make the best rulers. But to this day, Gazi Hüsrev Bey is generally viewed as a mix of Santa Claus, Jack Bauer, and the prime minister played by Hugh Grant in Love Actually. In other words, exactly the right person for the job. On Hüsrev’s watch, Sarajevo became known as “a flower among cities.” Walking around the city this past week, I have been astonished at the scope of the Bey’s projects. He not only built a gorgeous mosque but helped finance the Old Orthodox Church and a Franciscan monastery. Rich and I visited the school he founded (originally for boys, although later open to all) with plenty of scholarships and an emphasis on “the rational and traditional sciences.” Nearby we saw the Bey’s library, housing the most important collection of manuscripts in the country, many from Hüsrev’s personal collection. He built public bath houses, drinking fountains, parks, and a caravansary where visitors to the city could stay for several days for free; sadly this last is no longer in operation and Rich and I had to pay for an Airbnb. I was staggered to discover that the public toilet he’d had installed in 1530 is still in operation, and I felt I owed it to my readers to pop in for a look around so I could report on its condition. You’ll be glad to know that the plumbing has been upgraded since the Bey’s day. There are stalls, clean ceramic squat toilets, modern sinks, and an optional donation tin. The Bey also fed his people. “He opened a soup kitchen, a free place to eat,” Dalida told me, as she finished chopping the vegetables and brought out a large soup pot. “It was meant for the poor, but the food was so good everyone went. They say even Gazi Hüsrev Bey himself ate there.” Dalida and I were in the kitchen of her friend and employer, Uliana, co-founder of Balkantina, a small company organizing food tours and cooking classes out of a gourmet shop behind the Sacred Heart Cathedral in Sarajevo. Rich and I had dropped by the shop one day, and when Uliana heard about our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour, she invited us to her home to see Begova Čorba (Bey’s Soup) prepared as part of a traditional Bosnian dinner. When we arrived at her apartment, Uliana welcomed us with a platter of cheese, tomatoes, paper-thin ham, olive oil, and honey. “We always begin with a meze plate,” she explained. “And of course, rakija.” The traditional tiny servings of high-octane, homemade fruit brandy were poured and we toasted the occasion. After we’d nibbled our honey-dipped cheese, sipped our rakija, and been introduced to Uliana’s enormous Maine coon cat, Max, Dalida showed me the first, most characteristic ingredient in Bey’s Soup: a long string of dried okra. Now, I’ve had okra dishes that I loved, but I’ve run across a few that, as one writer so delicately expressed it, had the consistency of snot. Not to worry, it turns out that dried okra, commonly sold hereabouts on a string, eliminates sliminess, leaving a delicious vegetable bursting with vitamins and minerals. (If you’re pregnant or have asthma, high cholesterol, diabetes, or a compromised immune system, check out the medical benefits of okra.) No dried okra in your supermarket? Here’s how to dry it in your home oven. Bey’s Soup likes to simmer as long as possible, an hour and a half at least. While Dalida’s pot bubbled away on the stove, filing the air with the scent of onion, chicken, okra, and lemon, she whipped up a batch of dolmas (grape leaves and small yellow peppers stuffed with ground beef and rice). Then she tossed together a salad of tomatoes, cucumbers, and sour cream. By this time the soup had simmered sufficiently, and she removed the chicken from the bone and thickened the broth with a roux. Dinner was ready. The results were marvelous, a thick, delicious chicken soup for the body and soul. Just the sort of food to nourish a weary traveler newly arrived in the city, yet fit for any special occasion, such as getting to know new friends. Did Gazi Hüsrev Bey ever actually eat this soup? Who knows? But like the city of Sarajevo itself, Bey’s Soup will forever stand as a testimony to his generosity. And I like to think he would have enjoyed knowing that. One year into his reign, he set up a vakuf (endowment) to make sure the city would have the policies and funds it needed to keep his legacy going. Part of that document says: "Good deeds cause evil to flee, and the loftiest of all good deeds is charity. The loftiest of all charities is the one that lasts forever, while the most beautiful of all good deeds is the one that keeps on giving.... The efficacy of the vakuf will persist for as long as this world exists, and its work will continue until Judgment Day.” Not all the Bey’s good works are intact; the bath house and free lodgings closed long ago, and the school and library have relocated to larger quarters. But it’s pretty clear that if anything can survive until Judgement Day, it’s the pleasure of sitting down to a nice warm bowl of Bey’s Soup. Want to try this at home? Get Bey's Soup Recipe here. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY SOME OF MY OTHER FAVORITE COMFORT FOODS AND THESE STORIES ABOUT REMARKABLE PEOPLE Trying to recall exactly where Sarajevo is? See all posts about the Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. See all recipes and videos. Don't miss a single loony adventure or the next mouthwatering recipe. Sign up below for updates. Thanks for joining us on the journey. |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|