|

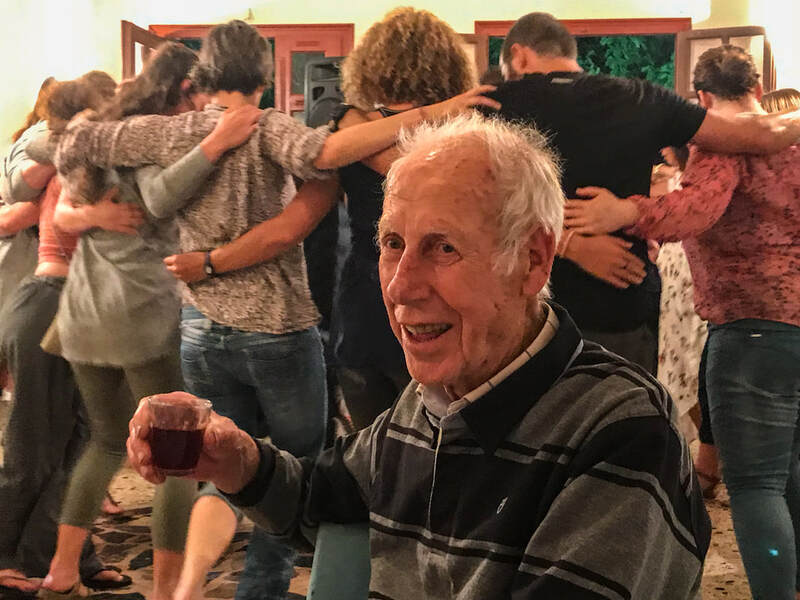

“Look at this island! People there live longer and healthier than just about anywhere. We should go. Maybe it will rub off on us,” I said to Rich a few years ago, while researching our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. “They did a study and 80% of the men between 65 and 100 still enjoy an active sex life.” Impressively, these guys still had plenty of energy leftover to get out on the dance floor as well. The island was Ikaria, Greece, one of the Blue Zones, regions famous for vitality and longevity. I went to an all-night party there, and the 93-year-old who opened the dancing was still at it when Rich and I stumbled out the door in the small hours of the morning. Yowza! There's a famous story about one island resident's powers of recovery. Several people on Ikaria told me the tale, and Dan Beuttner wrote about it in The Blue Zones. During WWII, a young Ikarian named Stamatis Moraitis had an injury that required treatment in the USA. He stayed there, married, and raised a family. At 60 he learned he had lung cancer; his five doctors gave him six to nine months to live. He decided to go back to the island so he could die among his own people; he and his wife moved in with his parents, and Moraitis retired to bed to await the inevitable. Old friends dropped by to share a glass of wine. Occasionally Moraitis would sit in the garden. One day he planted a few vegetables. He started puttering around tidying the vineyard. Pretty soon he was building an addition on the house. “Today,” wrote Buettner, “35 years later, he is 100 years old and cancer-free. He never went through chemotherapy, took drugs, or sought therapy of any sort. All he did was move to Ikaria.” Buettner asked Moraitis if he had any idea how he’d recovered from lung cancer. “It just went away,” he said. “I actually went back to America about ten years after moving here to see if the doctors could explain it to me.” Buettner asked what happened. “My doctors were all dead.” Stories like these are inspiring headlines asking, Should I Retire in a Blue Zone? The short answer is probably not. There are five identified Blue Zones: Sardinia, Italy; Nicoya, Costa Rica; Ikaria, Greece; Okinawa, Japan; and the Seventh Day Adventist community in Loma Linda, California. Although they all enjoy good weather, a laid-back lifestyle, and healthy eating, each has drawbacks. Ikaria, for instance, has no major airport or hospital and is a long ferry ride from anywhere. What the Blue Zone folks have discovered isn’t a fountain of youth, it’s a lifestyle that removes major stressors that make us age faster: time-pressure, isolation, unhealthy food, and the self-fulfilling expectation that at 65 we’ll begin to deteriorate in a variety of embarrassing and debilitating ways. People in the Blue Zones don’t share those habits and attitudes, and maybe it’s time we got rid of them, too. You don’t have to move abroad to do it, although there are places — like Seville — that do make it easier. Personally, I am doing my best to adopt these eight elements of the Blue Zone approach. 1. An active social life. In the US, we tend to live further apart, and everyone’s so busy even dinner with close friends requires planning weeks in advance. On Ikaria, people tend to stroll out most evenings after dinner and drop in on their neighbors for a casual chat. Likewise, in Seville impromptu gatherings are common. New expats join social clubs such as the American Women’s Club and InterNations to find kindred spirits. This is vital, says psych professor William Chopik, because “as we get older, our friends begin to have a bigger impact on our health and well-being, even more so than family.” 2. The Mediterranean Diet. All Blue Zoners follow some version of it, bucking the American fast food trend spreading across the globe. Here in Spain, it’s much easier to eat a natural, plant-based diet. I follow Michael Pollan’s shorthand definition of this approach: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” 3. A little wine every day. A few glasses of wine in the evening is standard on Ikaria. I generally have just one, but I am considering upping my game. Strictly for health purposes, of course. 4. No gym, just natural exercise. I remember years ago dragging myself to brutal fitness classes. Never again. In Blue Zones, daily life includes a lot of walking and other gentle exercise, such as gardening. A large Swedish studied showed gardening and similar forms of puttering around can increase longevity by 30%. Put the money you save on gym fees into tomato seedlings. 5. Daily siestas. People in the Blue Zones tend to rest after lunch. They don’t always sleep; sometimes they read, meditate, or do something equally relaxing. But they hit the pause button and feel better for it. “Don’t think you will be doing less work because you sleep during the day,” said Winston Churchill, who lived to 90. “That’s a foolish notion held by people who have no imaginations. You will be able to accomplish more. You get two days in one — well, at least one and a half.” 6. Sense of purpose. "Everybody needs a passion. That's what keeps life interesting,” said Betty White, who lived and worked to the age of 99. You'll never lack for things to do during a move abroad, but eventually you will settle in and then it's time to develop other interests. Travel is top on my list, with writing and painting in the offseason. Rich has taken online classes on happiness, grumpiness, memory, justice, and astronomy. He arrives at every meal with lots to talk about. 7. No retirement from life. I start worrying whenever I hear recently retired friends say, “I never do anything. I have six Saturdays and a Sunday every week.” Leaving a job can be liberating; becoming a couch potato is less so. George Burns, who lived to 100, agreed. “Retirement at 65 is ridiculous. When I was 65, I still had pimples.” 8. Positive attitude. Blue Zone people don’t fret about aging because they don’t view old age as God’s waiting room but rather as having more time to do things. “Get busy living or get busy dying,” says Morgan Freeman, actor, producer, and political activist. He got his pilot’s license at 65, and at 85 is still having fun doing guest roles on shows like The Kominsky Method. So to recap: No, you probably don’t want to live in one of the Blue Zones. Yes, their lifestyle makes sense, and it’s not a bad idea to see if you can adopt some elements of it wherever you may be. If you're dreaming of living abroad, see how many of these eight elements you’ll find in destinations you’re considering. Maybe someday you’ll be the 93-year-old life of the party on an island somewhere. It’s a tough job but somebody’s got to do it. I'd love to think Rich and I could learn to do this, but to be honest, I couldn't dance like this on my best day at any age. Dietmar & Nellia, you rock!

WELL, THAT WAS FUN. WANT MORE? If you would like to subscribe to my blog and get notices when I publish, just send me an email. I'll take it from there. [email protected] Yes, my so-called automatic signup form is still on the fritz. Thanks for understanding. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY

13 Comments

“Ya gotta give the guy credit,” I said around midnight, as Rich’s new friend led yet another 20-something woman onto the dance floor. “He’s got a lot of energy for eighty-four.” One of the locals laughed. “Eighty-four? He’s ninety-three.” I regarded the dancer with even greater respect. Not only was he the life of the panygyri, one of the traditional all-night parties with which Ikaria celebrates saints’ name days, but he was a living example of the locals’ legendary longevity. Designated as one of the handful of Blue Zones in the world, the island is full of people living remarkably long, healthy lives. I’d read articles on the subject aloud to Rich, adding, “We have to go there. Maybe it will rub off on us.” We arrived on the Sunday afternoon ferry and asked Dimitri, our hotel’s ever-helpful desk clerk, where to go for a late lunch. “Popi’s,” he said promptly. “The best food on the island, possibly all of Greece. Ten minutes’ walk up the coast road.” Twenty minutes later, as we staggered up yet another rise, we began to wonder if somehow we’d missed the place. Pulling out his phone, Rich discovered that Google had actually heard of Popi’s and informed us that it was just around the next bend, adding helpfully, “Closed. Opens again 1:00 AM.” “That can’t be right,” he said. We’d been told Ikarians refused to live by the clock, lightheartedly referring to any time of day as “late-thirty.” One young man I’d read about set off to buy coffee for his mother and didn’t return for three months. He’d run into friends en route to a panygyri, partied all night, gone to Athens, and gotten a temporary job. Presumably at some point he called home to suggest someone else should fetch Mom’s coffee. Obviously things were a bit looser around here. Still, opening at 1:00 AM? We soldiered on. Popi’s was just around the next bend, open, and serving some of the best food we’ve ever eaten. As we settled in the shade of the overhead vines, looking out over the tranquil Aegean Sea, we chatted with Zisis, whose mother had operated the place as a bar until he was born in 1993, at which point she converted it into a restaurant. I asked if he’d lived here all his life. “I went to work in Crete for a time,” Zisis told us. “Too much stress. It’s better here.” A relaxed lifestyle is one of the reasons ten times more Ikarians than Americans reach their eighties and nineties — and why their old age is rarely plagued with cancer, depression, or dementia. Another major factor is a diet based on the island’s wild greens, nutrient-rich herbs, seasonal vegetables, smaller amounts of food in general, and protein that’s mostly homemade cheese, fish, and goat. Goat is a surprisingly healthy option, far leaner than lamb or beef, with 40% less saturated fat than skinless chicken. And wild goat, it turns out, was the specialty of the house at Popi’s. Now I know what some of you are thinking: How could I consider eating one of those cute little goats that had bleated a greeting as we passed, peering curiously at us from the hillside next to the restaurant? Well, right now, Ikaria is hideously overrun with goats, thanks to EU subsidies rewarding larger herds. On an island with just 8423 residents, there are currently 35,000 goats, most roaming free and wreaking havoc on the ecosystem. Islanders are desperate to cull the herds to keep their island’s vegetation healthy. I decided to do my bit to help. “Want to try some wild goat?” I asked Rich. “Will you show me how you make it?” I asked Zisis. To my delight, they both said yes. Zisis explained the meat was super fresh, having been butchered that very morning. They raise their own goats and get more from relatives and friends. “Some goats are kept in pens, but many are free. And then the people must go hunting.” Asked to pin down quantities for the recipe, Zisis estimated he starts with about 2.25 kilos of meat. Because it’s so lean, formal cuts such as loin and shoulder aren’t practical; instead you make “village cuts,” dividing the meat any way you can, so long as it winds up a size that’s roughly suitable for cooking. You add lots of salt, pepper, and about three quarters of a cup of olive oil. You cook the meat in a ceramic pot at 200 degrees Celsius (400 degrees Fahrenheit) for an hour and a half to two hours. The cooking brings out the meat’s natural juices, but check it a few times and if it seems dry, add a little vegetable broth. When the meat is tender and the smaller bones practically liquified, you take it out of the oven and sprinkle it with fresh herbs. Often this includes oregano, which is full of vitamins, antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, digestive aids, and much more. A study showed the variety grown on the island is three times more nutrient-rich and aromatic than the kinds in other parts of Greece. (I hate to even think how our American corporate version might compare.) But the most important thing we learned is that wild goat cooked in its own juices and garnished with wild herbs tastes simply marvelous — succulent, rich, and comforting. Learning how to cook goat was just one small part of our effort to live as “Ikarianly” as possible while we’re here. We’ve eaten local foods, sampled the local wines, and danced at the panygyri. Letting go of our sense of time, we’ve been easing around town at our best approximation of the locals’ relaxed pace, stopping often to linger in cafés and on our favorite wharf-side bench. Don’t get me wrong; this isn’t an island of slackers. People get plenty done. They just do it their own way. Errands, for instance, often involve leaving their car in the middle of the street, their motorcycle at the curb with the keys in it, or their bicycle propped unsecured against a lamppost. Ikarians don’t sweat the small stuff … or the large stuff either. My goal in life is to find more ways to be like them. And of course, to eat more wild goat. |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|