|

“How can there be no taxis?” I demanded. “This is North Macedonia’s second largest city. Wikipedia called Bitola the transportation hub of the region. What gives?” “To be fair, there is a taxi. There’s just nobody in it.” Rich and I gazed at the empty yellow cab at the curb, the silent train station, and the handful of men quietly sipping Turkish coffee at the station café. As usual in such situations, I felt decisive action was called for, so I departed in search of the ladies’ room. I eventually located it at the far end of the station, and by the time I returned, Rich was standing beside our bags with a stranger and a bemused expression. “This guy will drive us out there,” he said. “Is he a taxi driver?” “I don’t know. He was walking by, and I thought he might belong to the yellow cab, so I said, ‘Taxi?’ And he said, ‘OK.’ Apparently he has a car and is willing to provide transport. He seems like a nice guy.” “Famous last words.” The stranger grabbed my suitcase and took off down the parking lot to a battered blue car. He wrestled with the latch on the car’s trunk, muttered what I assumed were a few choice Macedonian cuss words, gave up, and tossed the bags into the back seat. I climbed in after them, saying a quick prayer to St. Christopher, patron saint of travelers who are about to do foolish things.  You'll notice this map identifies Bitola as being in Macedonia, while the name of the country is shown as North Macedonia. In January 2019 a long-standing dispute with Greece was resolved by changing the name of the country to North Macedonia. My map program hasn't had time to catch up completely. Hope that clears up any confusion. We were (I hoped) on our way to Vila Dihovo, a rural guest house in a tiny village just fifteen minutes outside the city of Bitola in the foothills of Baba Mountain in scenic Pelister National Park. The guest house was family run, served homegrown produce and homemade beer and wine, and let you pay whatever you thought was right for lodging and meals. The driver — what are the odds? — delivered us safely to Vila Dihovo’s front gate for a modest fee. Our host Petar hurried out to greet us and grabbed our bags. We followed him into a stone building and up a set of wooden stairs festooned with a colorful little runner that had come loose from its moorings and was now a tumble of rucked-up fabric and scattered iron rods. I picked my way carefully along the bare wooden edges, wondering how many guests per week broke ankles here. Our small room was entirely filled with three massive wooden beds. “Are we sharing with another family?” I whispered to Rich. A modern shower stall, unable to squeeze into the minuscule bathroom, had inserted itself into the corner beside the largest bed, which was festively attired in purple seersucker sheets and a yellow canopy. We were just in time to join our fellow guests for dinner on a porch overlooking the garden. Meals, we soon learned, were one of the true perks of the place. Not only was the food delicious, but the conversations with our well-traveled fellow guests — British, Dutch, German, and American — were interesting and convivial. After breakfast, the others took themselves off on serious mountain hikes while Rich and I ambled about the village, admiring the old stone houses and making friends with the local dogs. I kept wondering how people survived without so much as a corner store or café, even if there was a city just fifteen minutes away by car. After a couple of days in the village, I was ready to embrace the more cosmopolitan pleasures of downtown Bitola. Settled during the Bronze Age, home to the ancient Greco-Roman metropolis Heraclea Lyncestis, serving as an international diplomatic hub under Ottoman rule (1382 to 1912), occupied in WWII by the Germans and Bulgarians … in short, Bitola has been at the crossroads of history ever since they invented history. While much of this was exceedingly uncomfortable at the time, today Bitola enjoys a rich legacy of architecture, archeological sites, and of course, cuisine. Which is why I was so dismayed to discover, on a first pass through town, that nearly every eatery's sign included the word "pizza." I asked our Airbnb hostess, Victoria, if she could recommend anyplace for traditional fare. “Most of the old dishes are only made at home,” she explained. “When people go out, they want something different.” She did recommend a couple of restaurants, but the next day, she and her husband, Mladen, invited us to come for lunch on Monday so I could see how she made two classic Macedonian dishes: zelnik (spinach pie) and turli tava (vegetable stew with chicken). As you can imagine, we accepted with delight. Monday morning, I joined Victoria in her kitchen as she began the pie dough. Unsatisfied with the texture, she repeatedly whacked the dough against the countertop to force out excess air. Note to self: this is the recipe I want to make when I'm having a very bad day. While the dough rested up after its ordeal, Rich and I accompanied Mladen on an expedition to fetch the spinach. We detoured into a tiny storefront serving what Mladen declared to be Bitola’s best burek (pie stuffed with cheese, meat, or other fillings). Rich and I felt we owed it to our readers to do a taste test and returned at the earliest opportunity. Mladen threaded his way through the old bazaar, a warren of small shops selling everything from clothes to kitchenware, and into the tarp-covered produce market. He explained that while a few things, such as bananas, were imported, most were locally grown and only sold in season. Lettuce was reaching the end of its time and would soon become tasteless. Cherries were just coming into their own, a bit expensive now, but delicious. Spinach didn’t seem to be available, so we would substitute blitva (a local green that’s like kale’s more delicate cousin). Returning with the blitva, I rejoined Victoria in her kitchen as she completed the zelnik. The filling of egg, cheese, and fresh greens was simple. Making the special rippled crust was more of a challenge and good fun to watch. Following local tradition, we began the meal with salad and rakia (fruit brandy), which we were assured was the best way to prepare the stomach for the pleasures that lay ahead. And I don’t think it was just the rakia talking when we all agreed that the zelnik was absolutely marvelous, the rich filling perfectly complemented by the delicate, rippling crust. The conversation flowed, turli tava emerged from the oven, and a bottle of wine went around. Eventually Victoria brought out her signature cake made with cherries from the tree shading the path to the door. At last Rich and I rose, groaning, from the table, said our farewells and stumbled upstairs to our apartment for a much-needed siesta. As I closed my eyes, I remembered Victoria beating the dough against the countertop to get the air out, at which point I said to her, “As I always remind my readers, perfection is not a requirement.” She laughed and set the dough down with a gentle pat. No, I thought drowsily as I dropped toward sleep, perfection isn’t a requirement. In fact, it’s never really possible. But some days, like this one, come very, very close. We've been on the road 68 days and are currently in Bitola, North Macedonia. We plan to cross over into Albania tomorrow morning. This is where we expect things to get seriously offbeat. If you haven't already subscribed, sign up here so you don't miss a single loony adventure or the next mouthwatering recipe. Thanks for joining us on the journey.

12 Comments

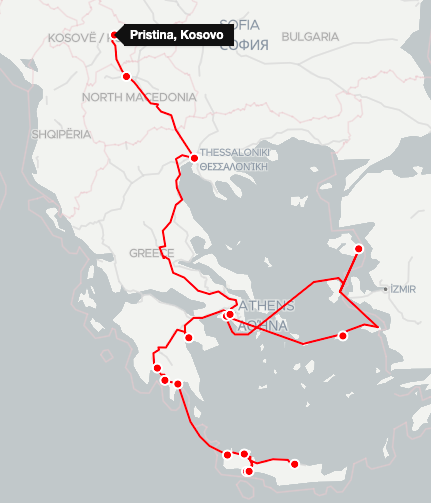

Like so many of Rich’s truly brilliant ideas, I thought it was totally insane when he first proposed it. Five days earlier, we’d left the warm hospitality of Greece and headed to the more bracing atmosphere of Skopje, the capital of what’s now known as North Macedonia. Skopje turned out to have a marvelous Old Bazaar, a Bohemian district bristling with hip eateries, and a just-completed plan to reinvent itself by filling the city center with fake baroque buildings, pseudo-classical statues, and decorative elements covered in gold spray paint. When he first caught sight of it, Rich said, “Call Las Vegas, see if anything is missing.”  All in all, Skopje had good entertainment value, and we enjoyed our five days there despite temperatures soaring into the nineties. Shortly afterwards, we’d arranged to go to a rural guest house in the cooler climate of North Macedonia’s mountains, but there remained a two-day gap. And that’s when Rich came up with his idea: a luggage-free overnight trip to Kosovo. “It’s just a two hour bus ride to Pristina, the capital,” he pointed out. “We can bring our toothbrushes and passports and be there by lunchtime.” As my regular readers know, we’ve traveled in France and California without any suitcases, just a few bare necessities carried on our persons. Afterwards I’m always barraged with emails, mostly about hygiene, so let me just assure you that on these occasions I wear fast-drying shirts and undergarments and launder them in the hotel sink every night. Reasonable standards can be maintained just about anywhere. Including, of course, Kosovo. “It’s a whole new country that we’ve never visited,” Rich added persuasively. “But why go luggage-free?” I objected. I’m a fairly minimalist packer, but I do like a few creature comforts. “It’ll just be for one night. Why drag the suitcases along?” Why indeed? So before cooler heads could prevail, I threw my toothbrush, sunscreen, and nightdress into my purse, Rich and I abandoned our bags to the tender mercies of the bus station's left luggage department, and we headed to the departure platform. And here was our first surprise. When they told us there was a bus to Pristina, somehow — call me crazy — I expected an actual bus. But apparently the Skopje-Kosovo run isn’t in high demand (go figure) so we discovered we’d be riding in a crowded van, ringing with Albanian pop music, air conditioned via the simple expedient of opening the side door for brief periods of time. It was a wonderful ride, through Skopje's teaming Albanian street market, over winding mountain roads, across two efficient and courteous border checkpoints, past broad green fields and villages with red tiled roofs, and finally into the heart of Pristina, the capital of Kosovo. Even those who love it best admit that Pristina is not a city with storybook charm. Nor does it contain a wealth of breathtaking monuments, unless you count the public library built in such a ferocious brutalist style that I suspect it will cause me nightmares for years to come. And yet, there’s plenty to love about Pristina. For one thing, there are all the tiny storefronts where people make their living providing such old-fashioned services as sewing clothes, mending shoes, even — and when was the last time you saw this? — repairing vacuum cleaners. Sure, there are supermarkets, but plenty of people shop at little fruit stands and in the marvelously labyrinthine farmers’ market, where next to the egg stalls you can see half a dozen hens pecking in the dirt or sitting on nests to hatch more inventory. Another surprise was America’s enormous popularity among the citizenry of Pristina. I saw a replica of the Statue of Liberty presiding over the freeway. The stars and stripes were on display in the lobby of our hotel, offered for sale at the farmers’ market, and displayed in the public library’s “American Corner,” a long-standing education and outreach program of the US Embassy. But the biggest red-white-and-blue love fest is reserved for Bill Clinton. It began during the Kosovo War of 1998 to 1999. I don’t pretend to understand the complexities of Balkan conflicts (does anyone?), but as near as I can make out, after Yugoslavia broke up in 1992, two of its larger states, Serbia and Montenegro, got together, called themselves the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and sought to control Kosovo, in part by ethnic cleansing. They were opposed by the Kosovo Albanian rebel group known as the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). Still with me? OK, then, here’s the part where Bill Clinton comes in; the locals give him credit for getting the US and NATO involved, bringing in the air support that turned the tide. As one shop owner told me, “If it wasn’t for Bill Clinton, we would still be fighting the war.” Bill was in town just last week to mark the 20th anniversary of the conflict’s end. No doubt he thoroughly enjoyed his ride down the Bulevardi Bill Klinton to view his life-sized statue waving at his Kosovo fans. But the most stunning surprise in Kosovo was the fabulous food. Blogger Jackie Nourse wrote, “Looking back at my 9-month trip around the world, I can honestly say that besides Italy (obviously), Kosovo cuisine was my favorite.” Why is this little corner of the world so blessed? As one cab driver explained, “This is where the Mediterranean meets the Orient.” It’s a match made in foodie heaven. Our first taste of this extraordinary gastronomy was the Albanian classic tavë kosi, baked lamb in yogurt sauce, ordered at the wonderfully atmospheric Liburnia restaurant. The lamb fell apart under my fork and melted in my mouth, perfectly complemented by the hot, creamy yogurt sauce and a crisp salad. Complimentary glasses of rakia (fruit brandy) appeared on the table. “For the digestion,” murmured our waiter. “Oh, well, if it’s medicinal…” said Rich. [See recipe for tavë kosi here.] The next day we popped into Furra Labi to sample some classic breakfast pastries. We ordered a spinach byrek, the Balkans’ favorite grab-and-go pie, and a slice of flia, think layers of pastry and cream. "And two coffees," I said. But here we hit a snag; the woman behind the counter explained they didn't serve coffee. Her boss, Leonard, saved the day. "No problem," he said. "I will go get you coffee. Macchiato?" “Of course,” I replied, having read this is what everyone in Kosovo drinks. The pastries were delicious, and when Leonard returned, it took just one sip to understand why Kosovo’s macchiato is considered a hot contender for best on the planet. When it was time to catch the van back to North Macedonia, we were sorry to leave Kosovo, which we’d found hospitable, entertaining, inexpensive, and delightfully free of tourists. It doesn’t have the gorgeous monuments we'd visited in Greece, or the architectural lunacy of its neighbor Skopje, but Pristina is a city brimming with energy, fueled on marvelous food and endless cups of macchiato. With or without luggage, I hope to visit Kosovo again soon, and often. 61 Days on the Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour

Yes, we've spent two months indulging in some of the world's favorite foods and finding out about local cuisine and culture. It's a tough job, but somebody's got to do it! Our culinary adventures have taken us to Greece, North Macedonia, and Kosovo (so far). For details, recipes, and videos: Our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour Heraklion, Crete: It's All About the Kindness of Strangers Holy Snail Day The Best Worst Town in Greece The Marvels of Lesbos Island Greece's Island of Longevity Breaking Bread with Strangers in Athens Greek Coffee: Freddos, Frappés & Fortunetelling Mysteries of Moussaka, Revealed We're now in the mountains of North Macedonia, in a tiny village called Dihovo, which along with the nearby town of Bitola is the epicenter of the nation's slow food movement. “In China, robots are making moussaka,” Stavros told me. “They freeze it and send it all over the world. Even some islands in Greece are serving such things. But this—” He broke into a smile and gestured to the dish he and his wife, Katerina, had labored over for the last three hours. “This is made with love.” It was also made with fresh vegetables from the farmer’s market and lavish quantities of olive oil, ground beef, butter, white flour, and whole milk. The moussaka at the Giannoula family restaurant is all-out, no-ingredients-barred, hedonistic indulgence, the kind of old-fashioned comfort food people ate before corporations, calories, and chemicals invaded the kitchen. Don’t even think of substituting low-fat milk or lean turkey meat in this recipe. “You could,” Stavros told me doubtfully, when I asked. “But it would not be the same.” As is so often the case, it was Rich’s sniffer — his legendary nose for good eats — that had led us to Taverna Giannoula. “I have a place in mind for lunch,” he remarked out of the blue last Thursday. “Where?” I demanded suspiciously. We’d just finished a long, uphill hike to Ano Poli, the sleepy old section of Thessaloniki, Greece. After hours of rambling past the faded buildings and sparkling vistas, I was hot, tired, and determined to keep heading in a downhill direction, preferably towards a cold beverage. “It's right around the corner.” “I love it already.” Arriving at Taverna Giannoula, I observed with pleasure the simple wooden tables, the cheerful red checkered cloths, and the small, immaculate kitchen. It was nearly 2:00 pm, still on the early side for lunch by local standards, and we soon learned that everyone in the place was a member of the family: Stavros the owner, his wife Katerina who served as chief cook, his brother Nikos who helped out, his mother-in-law who sat by the window sipping her soup and keeping a discrete eye on us, and his two young sons, who were playing a computer game in the back corner with friends, uttering occasional shrieks of muffled laughter. I collapsed into a chair at one of the three sidewalk tables, and Rich wandered inside to poke around. Stavros instantly invited him into the kitchen, where Rich peered into pots and eventually chose kolokithakia gemista, zucchini stuffed with pork and drizzled with avoglemono, the classic Greek egg-lemon sauce. Perusing the menu, I settled on smoky grilled eggplant topped with crumbled feta cheese. The meal was heavenly, and when I felt fully "reanimated" (as the Spanish put it), I went inside to pay my compliments to the cooks. When I mentioned we were on a Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour, Stavros and Katerina promptly invited me to come back on Monday to lean how to make proper Greek moussaka. On my second visit, the kitchen looked even smaller. It had begun life as a room about ten feet square, but now, fitted out for cooking and storage, the available floorspace was half that. Stavros, whose parents bought the restaurant when he was three years old, is an old hand at working in its cramped quarters, and as the moussaka got underway, he and Katerina wove back and forth across the room, handing off tasks with the practiced ease of professional jugglers. Even having to dodge around me as I zoomed in over their shoulders for closeups didn’t throw them off their stride. Stavros spoke English, so it was he who explained each step, but it was clear that Katerina was the head chef and that she took great pride and delight in her work. The moussaka recipe was her own creation, and as she pivoted from stovetop to sink to fryer, leaping up on her little stool to see check the eggplant sizzling on the high burner, dashing over to layer potatoes in the pan, she soon dispelled my foolish assumption that making moussaka was roughly akin to whipping up a batch of lasagna. This was serious cookery, performed by a serious chef. After an hour or so, she asked Stavros to make her a cup of coffee, and with a chuckle he showed me that he was serving it to her in a cup that read, “Mrs. Always Right.” [See the full moussaka recipe here.] If you make up a batch of Katerina’s moussaka — say for a family gathering or foodie pals — try to resist the urge to cut into it the instant it comes out of the oven, as the top layer, a creamy béchamel sauce, needs to cool and set. Now, I know what you’re thinking: béchamel sauce? That doesn’t sound very Greek, does it? That's because it's French, and you can thank Nikolaos Tselementes, the Jamie Oliver of 1920s Greece, for the upgrade. Born on Sifros Island in the Aegean Sea, trained in Austria, employed by embassies and top restaurants in Europe and America, he became one of the most influential Greek cookbook writers of his own or any other era. And when he got to the moussaka recipe, he abandoned the original topping — usually a custard, sometimes nothing at all — in favor of a thick, creamy layer of béchamel oozing with continental flair. His moussaka recipe became an instant hit and has inspired chefs around the world for nearly 100 years. Between the filming, baking, and post-oven cool-down, Rich and I spent hours at Taverna Giannoula, enjoying the ebb and flow of family life. Uncle Nikos picked the kids up from school and brought them to the restaurant for lunch. Another uncle stopped by to eat. The butcher on the corner brought Katerina a spectacular piece of beef, which Rich and I were called in to admire. Katerina’s mother observed everything with a twinkling eye, and seemed delighted to view the video footage, the two of us cozily communicating, via hand signals and facial expressions, our common admiration for her daughter's wizardry in the kitchen. It made me wonder, not for the first time, what it would have been like to grow up in such close family circumstances. In my childhood, lunchtime meant Dad at the office, Mom feeding the baby with one hand and downing her own sandwich with the other, and us older kids eating off trays in Catholic school cafeterias. As an adult, having worked in corporations, art studios, and my home office, I couldn’t imagine trying to navigate my day — every day! — under the eyes of three generations of my relatives and in-laws. Would it have made me nuts? Or perhaps added an element of love to the labor? A bit of both? I’ll never know. As I took my first, glorious forkful of Katerina’s moussaka, rich with vegetables, beef, and warm, creamy béchamel sauce, I thought about Chinese robots shipping their flash-frozen food products all over the world. It made me deeply grateful that at least in this little corner of Greece, the old ways are still honored. Food is grown on nearby farms, sold in the shop on the corner, prepared in a kitchen surrounded by people who love one another, and served with kindness and ice cold local beer. It doesn’t get better than this, I thought. The world seems to be getting faster all the time now, which makes it extra comforting to know that there is still slow food on the menu somewhere, if we just take time to look for it. In case you're just joining us, here's the scoop on Our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour

Rich and I decided to set off on an open-ended, unstructured journey to sample some of the world's best comfort foods as a way to gain insight into the local culture. We started April 20 in Crete and plan to travel until September-ish. You'll find highlights, recipes, and videos in the stories below. Our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour Heraklion, Crete: It's All About the Kindness of Strangers Holy Snail Day The Best Worst Town in Greece The Marvels of Lesbos Island Greece's Island of Longevity Breaking Bread with Strangers in Athens Greek Coffee: Freddos, Frappés & Fortunetelling How did we get started? First We Moved to Seville Then Came the Railway Travel Through Eastern Europe Where are we now? After two weeks resting up in Thessaloniki, Greece, we did manage to get those elusive bus tickets we wanted and have just arrived in Skopje, North Macedonia. The next few weeks we'll be roaming around various Balkan countries, and the timing of these blog posts may become a bit more erratic. Just saying. Rich and I thought we were prepared for anything — trains leaving at 3:30 AM, running once a week, or requiring awkwardly timed changes at obscure junctions. It never occurred to us that there might be no public transportation whatsoever between two major European cities just 146 miles apart. “Trains?” said the man at the Thessaloniki railway station, as if this were a foreign concept. He peered at my handwritten note. It read, “Thessaloniki —> Skopje Wednesday June 12.” He shook his head. “No. No trains to Skopje. After June 15, is possible. Now, no.” Rich shrugged. “Looks like we’ll be taking the bus.” Or maybe not. The lady at the nearby bus counter said, “Tomorrow. Next day. After that no.” “We want to go next week,” I said. “No. Tomorrow, next day, then is finished. No more buses.” “Ever?” I asked. She shrugged. “This is Greece.” Enough said. This left us in something of a quandary. Our goal is to complete the entire trip on public transit — trains, buses, ferries, the occasional taxi — never driving a car or taking a plane. What to do? We returned to the railway counter. “Could we buy tickets now for June 15?” I asked. It would mean three more days in Thessaloniki — not exactly a hardship. “No. I have no tickets. Maybe June 15, maybe not.” He paused then added, “They are Serbian trains.” As if that explained everything. Rich and I walked out of the railway station laughing and shaking our heads. There was a time we might have been a trifle perturbed at the idea that an apparently insurmountable obstacle was blocking our progress. But like everyone else in Thessaloniki, we were floating along on such a powerful caffeine high that nothing really bothered us. Coffee is the lifeblood of this city, and everyone, including us, is drinking plenty of it. Coffee houses abound, sometimes five or six on a block, doing brisk business at all hours of the day and night. Younger locals are sipping from go-cups on the street, in the shops, and at work. What’s in all those go-cups? Frappés and freddos, relative newcomers on the scene. For centuries, folks around here drank nothing but traditional Greek καφές, a thick Turkish-style boiled brew that somehow manages to taste like American instant coffee. And while you can order it sketos (without sugar), it’s so bitter nearly everyone takes it metrios (one heaping teaspoon of sugar), glykos (sweet, two teaspoons), or variglykos (very sweet, four teaspoons, at which point it’s more or less Red Bull). Then a single impulsive moment at 1957 trade fair changed the nation’s coffee culture forever. The Swiss manufacturer Nestlé was in town promoting instant Nescafé and a short-lived product involving chocolate milk made in a shaker. One day Nescafé employee Dimitrios Vakondios felt the need for caffeine but couldn’t find any hot water. On impulse, he borrowed the shaker from the chocolate milk rep and mixed Nescafé instant coffee with cold water and ice. The idea of iced coffee — shockingly radical yet undeniably attractive in this hot climate — caused an overnight sensation in Thessaloniki and soon became the drink of choice for hipper Greeks everywhere. The new drink was dubbed the frappé (from the French "frapper," meaning to hit, referring to the ice crashing around in the shaker). It can be served with varying amounts of white or brown sugar, with or without condensed milk, and — if you really want to feel the love — a scoop of ice cream. Frappés are so popular here that even Starbucks has added it to their menu. The frappé reigned supreme until the 1990s, when it was overtaken by the freddo, a similar iced drink made from the classier Italian espresso. It can of course be configured to any degree of sweetness, and if you want milk, you ask for a freddo cappuccino. Which is better? Rich and I decided to consult Natasa, the owner of Thessaloniki’s historic and arguably hippest café-bar: Thermaikos. Here’s what we learned from Natasa and her barista, Athanasia. Both drinks are fun, and if you get them fully loaded, they’re more like milkshakes than coffee drinks — which is no doubt why they’re so popular with the young. But if you hope to live to a ripe old age, you might want to stick with traditional Greek coffee. “Researchers studying heart health say that a cup of Greek coffee each day may be the key to the longevity of people on the Greek island of Ikaria, who live to age 90 and older," reported Dr. Gerasimos Siasos of the University of Athens Medical School. Greek coffee can determine your future in another way as well: the grounds are used by local psychics to predict the future. Which is why, when Rich and I were stymied in our efforts to leave town, I found myself at the café Ωκεανος (Ocean) for a reading with their resident clairvoyant. Elena is much in demand, and I had to take a number and sip my Greek coffee for over an hour while she did other readings. Shortly before my turn, she came and swirled the coffee around in the cup, tossed the liquid into a bucket, and upended my cup in its saucer to drain. Ten minutes later she was back, set the cup upright, and peered into my future. First, she saw a female relative who was giving me trouble. “A dark-haired women, a bit heavy.” Four generations of my relatives passed before my mind’s eye; no one matched the description. The reading stumbled along with the theme of business papers recurring constantly and the hope that some money might be coming to me. Somehow we never got around to the subject of travel arrangements. “What’ll we try next?” I asked Rich. “Travel agencies. Somebody must go to Skopje.” The first travel agency confirmed that no public or tourist buses were running to Skopje in the foreseeable future. As we emerged onto the street, a toothless old woman in black tried to shove a picture of the Virgin Mary into my arms. At my repeated refusals to buy it, she hurled a curse at me and stomped away. She and I had been through this routine three days earlier, just before our transit problems began. Hmmm, could there be a connection? “Do you think I need to buy some of her art to get our karma back on track?” I asked Rich. “Let’s hope not.” Eventually we learned that bus service has been extended a few days while negotiations continue. So we may or may not leave town next week, I might have an unknown, dark-haired, heavyset female relative plotting against me, and it’s possible I’ll have to buy some cheap religious art to lift a curse. In other words, we don’t have a clue about what the future holds. But then, does anyone? In the meantime, I’ll just relax over another cup of καφές. My Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour In 2019 Rich and I set off on an open-ended, unstructured journey to sample some of the world's best comfort foods — I know, a tough job, but somebody has to do it! Each meal gave me fresh insight into the character of the local culture. Right now I'm working on a book about my adventures; stay tuned for updates. My Other Eastern European Adventures My Move to Seville |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|