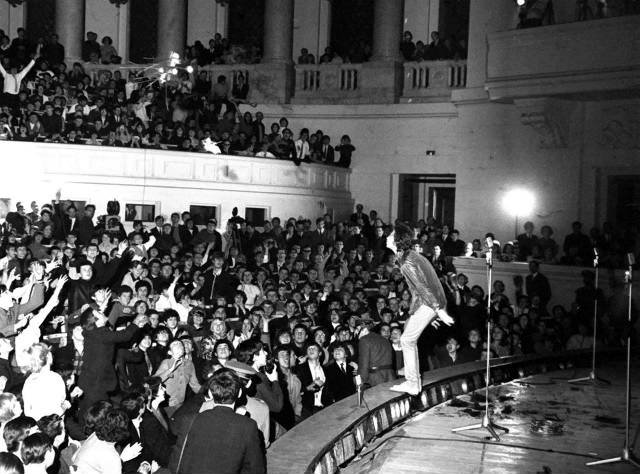

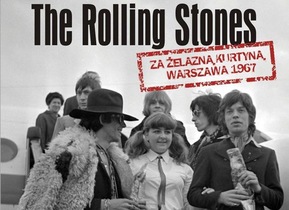

“When the Rolling Stones played here in 1967, there was a small problem about the fee,” said Lucas, with the air of a man setting you up for a delicious punchline. We were in downtown Warsaw, standing in front of Poland’s tallest building, the 1955 art deco high-rise originally known as the Joseph Stalin Palace of Culture and Science. “How did the Rolling Stones come behind the Iron Curtain? The daughter of First Secretary Wladyslaw Gomulka was a fan, and she pestered and pestered until it was agreed. The concert was only for communist party leaders and their families. After, when the Stones received their payment, they go to the bank, and find out the money cannot be exchanged or transferred. The money must be used in Poland. They go to the store to buy something, but in those days there is nothing to buy. A few potatoes. Some soap. And vodka. So they bought enough bottles of vodka to fill an entire railroad car. But then they learn the railroad car of vodka also cannot leave Poland. So they donate the vodka to the Polish Artistic Agency. It took them 30 years to drink it all.” Lucas was our guide on the 3-Hour Communist Tour of Warsaw in an Original Socialist Van, which like just about everything we encountered in the Polish capital, didn’t turn out as expected. It was meant to be a small, English-language tour, yet somehow it included an entire Lithuanian bachelor party that hadn’t slept in days, four Spaniards who spoke almost no English, and three others besides ourselves who actually listened to Lucas. We drove around town for hours in two noisy, sweltering Soviet-era vans. The Lithuanians disappeared somewhere around the old headquarters of the Central Committee of the Polish United Worker’s Party, and the rest of us went on to the cheesy Museum of Life Under Communism. Shots of cheap, mint-flavored and cherry-flavored vodka went around, and we were supposed to view some 1950s propaganda films and sample the traditional, down-and-dirty snack of bread with pork lard and pickles, but none of that ever materialized. “The lard sounded revolting,” I said to Rich. “But I’m kind of sorry we’ll never have the chance to try it.” But this was Warsaw, where the only thing you can count on is being surprised. Two days later, on the gourmet Eat Polska food tour, we found ourselves sitting down to platters of pork lard, brown bread, and gerkins. It actually tasted pretty good, especially when washed down with high-grade, unflavored vodka. “In the past, before McDonald’s and new kinds of processing arrived, the food here was more flavorful and nutritious,” said Ula, our gastronomic guide. “There wasn’t much food in the stores, but at least everything was fresh and not full of chemicals. Many people here are quite nostalgic for food from the 1970s.” After the lard incident, we realized that there wasn’t much point in even trying to control events. One night we tried to go to the Copernicus Planetarium’s classical music under starry skies, but that was sold out, so we wound up with tickets to what we thought was a night of Pink Floyd under starry skies. Instead it turned out to be the mind-blowing Dark Side of the Moon. After that hallucinatory extravaganza, we attempted to take Uber back to our apartment, but found the main thoroughfare blocked off for a street party. Go around? Hell no. We leaped out and joined in, winding up in a courtyard where a band was playing Day-O (The Banana Boat Song). When the crowd chimed in with the chorus, we did too. Hey, when in Warsaw…  Tripe soup: I have to confess, I'm not much of a fan. Tripe soup: I have to confess, I'm not much of a fan. We made one more attempt to hear some classical tunes, heading over to the vast Lazienki Park for the traditional Sunday afternoon open air Chopin concert. Arriving too late for the early show, we wandered about until we heard sixties rock music wafting out from behind the Palace on the Island. We sat down at the water’s edge to enjoy the familiar tunes, including — what are the odds? — “Money,” one of Pink Floyd’s hits from The Dark Side of the Moon. You see where I’m going with this. If we’d tried to stick to our own plans, we’d be singing I Can’t Get No Satisfaction and having our 19th nervous breakdown. Instead, we relaxed and enjoyed Odpowiedź Niesie Wiatr, Bob Dylan’s Blowing in the Wind sung in Polish. We thought we were visiting Warsaw, but it turned out we were re-visiting the sixties and seventies. And that’s good fun in any language. By now we've been on the road two months, and we've covered 3573 km / 2220 miles, mostly by train. Highlights have included zany Amsterdam, the German city of Lübeck on the edge of the Baltic Sea, the Stockholm disaster, the new foodie mecca of Helsinki, Finland, futuristic Estonia, and a kookie visit to Riga, Latvia. We headed south to Šiauliai, Lithuania, where history — and great chocolate — were made. Vilnius — and the tiny Republic of Užupis— taught me about miracles; I learned about devils in southern Lithuania and northern Poland. To follow our adventures as they unfold, subscribe to my blog, like my Facebook page, and keep checking the map of our journey.

6 Comments

“There is no way I’m going into the Devil’s Museum until I have coffee,” I said to Rich. “Keep your eyes peeled for someplace — anyplace — that’s open.” This was not looking likely. We were in Kaunas, Lithuania, which we’d chosen as a stopover on our roundabout way to Warsaw. The direct rail route would have taken us through Belarus, which required visas (and a taste for danger) we did not possess. Googling cities safely inside Lithuania, I came upon Kaunas and the city’s singular attraction that’s earned a spot on so many weirdest-in-the-world lists: The Devils' Museum. That clinched it. Days later we were on Satan’s doorstep in a neighborhood devoid of coffee houses. “So this is hell,” Rich said. But wait! Two blocks away an open door beckoned. Putvinskio 48 turned out to be a cosmopolitan restaurant that was only too happy to provide us with foamy cappuccinos, slivers of apple pastry, and the translation services of the owner’s daughter, Diana, who happened by as we struggled to order. Clarification of the menu quickly morphed into a lively conversation ranging over her current veterinary studies in Ireland, things to see in Kaunas, and what to order when we returned that night for dinner. The Devils' Museum wasn’t nearly as convivial. The staff looked depressed and no wonder, surrounded by 3000 images of the Prince of Darkness, many of which will be showing up in my nightmares for years. The original collector was Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, an artist born on Halloween, 1876. By an odd coincidence, two friends marked his thirtieth name day with gifts of Beelzebub statues; one, a prominent priest, urged him to start collecting. Fifty years later Žmuidzinavičius owned 260 diabolical images, and friends presented him with thirteen place settings of custom-designed Satan-themed china. In 1961 he donated his collection to the State, and additions continue to pour in from fans of the Evil One and people wanting to divest themselves of demonic souvenirs that no longer seemed quite so amusing when they got them home. That evening, we refreshed our spirits with a return visit to Putvinskio 48, where we enjoyed some of the best food we’ve had in the Baltic States. But Kaunas is so much more than the Devils' Museum and artistic beet soup. The next day we visited the Atomic Bunker Museum, located six meters below an old factory on the outskirts of town. We arrived to find a deserted industrial complex, an open door marked Atominis Bunkeris, and a very long stairway going down. We knew we were in the right place when we passed a banner that said, “Better be an informer for Trip Adviser than the KGB.” Marius, our engaging young guide, waited in a vast underground room lined with Soviet paraphernalia and proceeded to describe each item with a collector’s enthusiasm. “This is the desk of KGB leader! Here is secret exit to tunnel; it ends near supermarket!” Various side rooms displayed cameras cunningly hidden in belts, handbags, cigarette packets, and coat buttons; plaster models of body parts showing the grisly effects of radiation poisoning; and the museum’s pride and joy, the gas mask collection. The tour was fascinating, and at the end of it, Marius gifted us with a gas mask. “I love it,” I said, pulling it on. “Do you think it’s my color?” “It really brings out your eyes,” Rich said. Seeking another stopover on the next phase of our journey to Warsaw, I ran across a reference to the Wolf’s Lair in northern Poland. WWII buffs will remember this was the Eastern Front military headquarters where Hitler spent 800 days and narrowly survived an assassination attempt by one of his officers. Film buffs will remember that officer was played by Tom Cruise in Valkyrie.  We made it! Our ticket from Elk to Giżycko. We made it! Our ticket from Elk to Giżycko. Hitler chose the spot for its inaccessibility, and as we discovered, it is still one of the least convenient places to reach in all of Europe. It took Rich days to work out a route. We caught a train to Suwałki just across the Polish border, then a bus to Elk, a town famous for celebrating Opposite Day, in which everyone says the reverse of what’s true. This is supposed to occur January 30, but evidently they were willing to make an exception in our case. We had a tight connection, so we leapt off the bus and tore into the Elk train station, gasping, “Two tickets for Giżycko.” The clerk slowly wrote down a time three hours later. “Isn’t there one now?” She shook her head. A fellow passenger said, “Yes, there is one, but it leaves in one minute. You will never catch it.” Dashing down the stairs, we raced through the underground tunnel and stumbled up onto the platform just as the final whistle blew. We shouted incoherently at the conductor who, astonishingly, waved us on, taking out his radio and asking the engineer to hold up the train a moment. So that’s Elk: the best and worst stop ever. From Giżycko, we took a train to the small town of Kętrzyn, where we hired a taxi to take us the last few kilometers. All I could think of, as we drove through the quaint villages, was that it was from these sweet, old, peaked-roof houses that the SS collected the fifteen terrified girls who served as Hitler’s food tasters at Wolf’s Lair. For 800 days they ate his food and waited to see if it had been poisoned. Afterwards, Margot Wölk recalls, “We used to cry like dogs because we were so glad to have survived.” And that, I think, is why we visit places like the Devils' Museum, the Atomic Bunker, and Wolf’s Lair: to remind ourselves that some of us, somehow, manage to survive even the darkest times. And that those times eventually end. Today, Wolf’s Lair lies in ruins, the colossal bunkers blown up by the Nazis as they fled before the Red Army in 1945. So there Rich and I were, invading Hitler’s top secret hideout. Was it worth the fuss to get there? You bet. For one thing, you can’t help but have profound thoughts in a place where great evil has been perpetrated. For another, I somehow felt that all of us on that site were helping — as we say in California — to cleanse its aura. We brought normality into a place where it was once in very short supply. Every culture has exorcism rituals, and perhaps in this age of world travel, tourism offers a new way ordinary people can help banish the demons of the past.  Not to keep you in suspense, Rich and I have now arrived in Warsaw. To date we've covered 3420 km / 2125 miles, mostly by train. Highlights have included zany Amsterdam, the German city of Lübeck on the edge of the Baltic Sea, the Stockholm disaster, the new foodie mecca of Helsinki, Finland, futuristic Estonia, and a kookie visit to Riga, Latvia. We headed south to Šiauliai, Lithuania, where history — and great chocolate — were made. Vilnius — and the tiny Republic of Užupis — taught me about miracles. To follow our adventures as they unfold, subscribe to my blog, like my Facebook page, and keep checking the map of our journey. According to local legend, the Miracle Tile of Vilnius, Lithuania has the power to make wishes come true. Some say you have to stand on it, twirl around three times, jump in the air, and clap your hands to get your wish. Others suggest this tradition was started mainly to provide the locals with a little innocent amusement and has nothing to do with getting what you ask for. I’m not going into all the details of my experience but suffice to say that if you’ve been fretting about the long-term viability of the planet's ecosystem, you can relax; it’s sorted. You’re welcome. The Miracle Tile also marks one end of the longest human chain ever assembled. On August 23, 1989, two million people in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania — one quarter of the population of those three countries — joined hands in a 420-mile line running from Tallinn, Estonia through Riga, Latvia and ending (or starting, depending on your perspective) right on the Miracle Tile of Vilnius. The men, women, and children in that long line were protesting Soviet occupation, which had recently been revealed as the illegal result of secret protocols in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between the Nazis and Stalin, who reached a clandestine agreement allowing Russia to occupy the three Baltic countries. This revelation provided legal justification for dismantling Soviet authority in the region, and on that day in 1989, two million people braved the wrath of a superpower to stand up for their freedom. By 1991 they had it. Was this the Miracle Tile at work? I’ll leave that for you to decide. For some in the Lithuanian capital, freedom from the Soviets was only the beginning. On April 1, 1997, the residents of Užupis, a small, bohemian district tucked inside a loop of the Vilnia River, declared themselves the independent Republic of Užupis. They have their own flag, currency, constitution, president, anthem, and an army of 11 men; if you go there, you can have your passport stamped. The Republic of Užupis isn’t recognized by any official government, and no one (including, I suspect, the ringleaders) is quite sure where on the serious to tongue-in-cheek spectrum the whole enterprise falls. One of the projects that brought the group together was convincing the city to enliven the landscape with a statue of the outrageous musician Frank Zappa. Saulius Paukstys, who spearheaded the movement, faced considerable resistance from authorities. "They said: 'What has he got to do with Lithuania anyway?' We said: 'Nothing really.' Then someone convinced them that Zappa had Jewish features and seeing as Jewish history is very important to Lithuania, they plumped for that." The residents of the Republic of Užupis are mostly artists, and playfulness and creativity are some of the tiny republic’s most cherished ideals. The constitution, drafted in a local bar, is a treat to read. Here are some of my favorite provisions: Everyone has the right to make mistakes. A dog has the right to be a dog. A cat is not obliged to love its owner, but must help in times of need. Everyone has the right to die, but this is not an obligation. Everyone is responsible for their freedom. As the republic’s first president, Roman Leleikis, explained at the time, “We’re trying to energize a community by asserting our independence. It’s very different from the independence gained in ’91, but we’re trying to foster the same spirit so that people can make things happen for themselves. That’s a trait they lost through 70 years of oppression.” Today, the people of Vilnius are making things happen for themselves, and one way they’re doing it is through the sharing economy, with peer-to-peer transactions that link neighbors to neighbors, visitors to locals. You can rent lodgings from Airbnb, get around town with Uber or in a City Bee car, and now, thanks to the entrepreneurial spirit of a local chef named Ruta, you can share a meal in a private home via EatWith. Rich and I signed up to go to Ruta’s home for a dinner made from homegrown vegetables and herbs, berries picked in the forest in the Baltic tradition, and seasonal ingredients from the market. Ruta’s training began in her grandmother’s kitchen. “For me, cooking became a way of making people happy,” she told us. “When I heard about EatWith, I knew I had to convince them that I should be part of that here in Vilnius.” The screening process was rigorous, but Ruta persevered and became the first — and so far, the only — EatWith host in Lithuania.  The dinner was delightful. Rich and I lingered long at the table with Ruta and her husband, Vidmantas, discussing everything from the state of the world to the ingredients in each mouthwatering morsel on our plates. As I dipped my spoon into the homemade coffee mousse, I thought about all the years of my childhood when I had stood in terror of the USSR and wished with all my heart that the Iron Curtain would come down. I don’t know how much of the credit belongs to the Miracle Tile, but however it happened, I am still astonished and deeply grateful that the Baltic States are enjoying their freedom, and I hope they will hold on to it for a very long time to come. Soon we'll be wrapping up our time in the Baltic States and heading south into Poland to start the second half of our trip. To date we've covered 2976 km / 1849 miles, mostly by train with a few ferries and the odd bus thrown in. Highlights have included zany Amsterdam, the German city of Lübeck on the edge of the Baltic Sea, the Stockholm disaster, the new foodie mecca of Helsinki, Finland, futuristic Estonia, and a surprisingly kookie visit to Riga, the capital of Latvia. We spent a few days in the Latvian countryside, in the small town of Kuldīga, then headed south to Šiauliai, Lithuania, where there appeared to be nothing to do — until there was too much to squeeze in. We're currently in Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital. To follow our adventures as they unfold, subscribe to my blog, like my Facebook page, and keep checking the map of our journey. “I think we’ve finally found it,” I said to Rich. “A town where there is literally nothing to do.” We were dragging our suitcases from the train station toward our hotel, walking past endless bland apartment blocks, unrelieved by a single shop, café, or even newsstand. After the dizzying mix of zingy modernity and storybook charm we’d encountered in other Baltic towns, Lithuania’s Šiauliai (it’s pronounced Show-lay and means “sun”) seemed desperately drab.  “Remind me again why we came here,” Rich said. As usual, we’d decided to break a long train ride — in this case, from southern Latvia to the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius — with a two-day stopover that would offer us a glimpse of local culture. But why had we picked Šiauliai in particular? “There’s a Chocolate Factory,” I recalled. “And the Cat Museum.” Rich rolled his eyes and bent down to check on the duct tape that was unraveling from the bottom of his suitcase. Two hours later we were sitting at a sidewalk café table on the main pedestrian street, flipping through folders from the tourist information office and trying to juggle our schedule to fit in everything we wanted to do. “Let’s go to the traditional Lithuanian kosher dinner at Chaim Frenkel’s Villa this evening,” I said. “Then we can catch the music at Juone Pastuoge tomorrow. I just hope we’re not too tired after visiting the Hill of Crosses and the Battlefield of the Sun. Do you think we’ll be back in time to catch the fado concert?” The Cat Museum had long since been jettisoned from the agenda, but Rich was still standing firm on the need to visit the Chocolate Factory. I was more interested in seeing two nearby sites where spectacular acts of rebellion had taken place. For this we had to hire a taxi and drive twenty minutes out of town to the marshy banks of a river where in 1236 a small band of Lithuanian pagans turned back the tide of the Baltic Crusade. The Pope had sent the German warrior-monks known as the Livonian Brothers of the Sword to take over the region for the Church. The Brothers didn’t think the Lithuanian pagans would put up much resistance, and when they encountered a small band blocking them at a river forge, they didn’t even bother to engage. Reluctant to risk their horses in the swampy ground, even more disinclined to fight on foot, they simply made camp and went to bed, no doubt hoping the pagans would give up and go away. The Lithuanian pagans, delighted with this stroke of luck, spent the night mustering every man and javelin in the region, surprised the Brothers with a morning attack, and defeated them soundly. This upset victory, known as the Battle of the Sun, galvanized other rebellions, and helped launch the vast and powerful Grand Duchy of Lithuania that lasted centuries and reached from the Black Sea to the Baltic coast. When we pulled up at the site, our driver looked at us and shrugged. The spot may have been historically significant but visually it was pretty underwhelming. The Hill of Crosses proved to be considerably more photogenic. Locals began placing crucifixes here after the unsuccessful 1831 Uprising staged by young army officers rebelling against Tsarist Russia. The bodies of rebels who perished weren’t returned to the families, so to mark their passing, relatives put up wooden crosses on the site of an old hill fort. The tradition continued during the 1863 Uprising, the War of Independence, the first Soviet occupation, the Nazi occupation, and the second Soviet era which lasted from 1944 to 1990. The Soviets bulldozed the site three times, burning the wooden crosses, tearing apart the metal ones, crushing the plaster and concrete statues. Each time, the locals snuck back, cleaned up the site, and put up more crosses and other religious images. Rumors of the appearance of the Blessed Virgin in the 1960s only increased the site’s popularity, annoying the Soviets even further. Today there are hundreds of thousands of crosses, and pilgrims visit from around the world. The gift shop was doing a brisk business in wooden crucifixes hand carved by local craftspeople, and we saw several small groups of pilgrims climbing the hill to add theirs to the staggering collection. Šiauliai’s rebellious spirit isn’t much in evidence today. The city lost its architectural vitality during World War I, when fire destroyed 85% of the town and rebuilding was more practical than aesthetic. Although there’s a sizeable university, we saw very few tattoos or piercings, little graffiti, and not a single dive bar. The whole place seemed downright upright. But that doesn’t mean it was dull. Last night, we went to the popular open air music hall Juone Pastuoge to hear what was billed as “country music.” We spent the entire evening trying to decide if we were hearing American country-western music sung in Lithuanian or traditional Lithuanian folk tunes performed with a Nashville beat. No matter. The crowd was cheerful, little kids darted around underfoot as families and groups of friends dined at long tables, and couples, including us, took to the dance floor. It was one of those rare occasions when the world reminds you that you really are exactly where you should be, doing exactly what you’re supposed to do, living life as it’s meant to be lived.  Of course, our visit to Šiauliai didn’t really peak until the next morning, when Rich finally made it to the Chocolate Factory. I stayed behind to work on this post, and a few minutes ago he returned with some of the most outstanding chocolates I’ve ever eaten, the kind that are freshly made from natural ingredients and aren’t even pretending to worry about fat content or what they’re going to do to your waistline. “I love this town,” I said, when I could speak again after the bliss of the first truffle. “There is just no end to the fun things to see and do here.” IN A FEW DAYS WE'LL REACH THE HALFWAY POINT OF OUR JOURNEY. We're spending 3 months on trains and ferries, with an open itinerary and small (slightly frayed) suitcases. Distance covered so far: 2790 km / 1734 miles. Highlights have included zany Amsterdam, the German city of Lübeck on the edge of the Baltic Sea, the Stockholm disaster, the new foodie mecca of Helsinki, Finland, futuristic Estonia, and a surprisingly kookie visit to Riga, the capital of Latvia. We spent a few days in the Latvian countryside, in the small town of Kuldīga, then headed south to Šiauliai, Lithuania. To follow our adventures as they unfold, subscribe to my blog, like my Facebook page, and keep checking the map of our journey. |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|