|

"When you were a kid in New Jersey,” I said to Rich, “did you ever think you’d move abroad?” “Never.” “Me either. I thought it was something that people only did in books and movies, not in real life.” So you can imagine how gobsmacked we were a dozen years ago when we found ourselves leaving Cleveland, Ohio to settle in Seville, Spain. How — and why — do (reasonably) sane, (mostly) normal people like ourselves decide to leave behind all that's comfortable and familiar to venture forth into the unknown? To get to the heart of this question, I decided to interview the one person who could really shed light on the subject: my husband, Rich. What took you overseas for the first time? I was in the Navy from 1966 to 1969. First I was on a refrigerator ship out of Norfolk, Virginia carrying supplies to the 6th Fleet in the Mediterranean; later I went to Vietnam. But it wasn’t until I was out of the service and visiting relatives in Ireland that I realized how great it was to connect with another culture. Looking back, I regretted that I’d wasted the opportunity to get to know the Vietnamese, Italian, French, and Spanish people I’d encountered during my time in the military. I vowed to make up for that in the future. Since then I've traveled to more than 60 countries, and I always make an effort to talk with locals. [Note: For more about how to connect with locals, click on any of the photos below.] What inspired you to move abroad? After I took early retirement, I felt like my world was getting smaller and smaller. I needed a sense of adventure. Visiting southern Spain, I realized I’d found what I was looking for. It's challenging but at the same time much more relaxed and less money-driven. Family and friends are treated as genuinely important, not something to fit into the margins of your day. In the US, even something as simple as having a coffee has to be scheduled weeks in advance, but in Seville, it’s far more spontaneous; friends ring your doorbell in passing and invite you to join them at the corner café. In some ways, it reminds me of the America of my childhood years. What’s the most embarrassing moment of your expat career? Oh God, there are so many. OK, here’s one. When we first moved to Seville, I wanted to make a small repair requiring a screwdriver. I checked the dictionary, and all the way to the hardware store I kept muttering “destornillador, destornillador, destornillador” (screwdriver, screwdriver, screwdriver). Unfortunately, the minute I stepped through the door, my mind went blank and I blurted out a similar word, ordenador (computer). This caused such intense mutual confusion that I was forced to abandon the attempt and flee the scene without buying either a screwdriver or a computer. At the time, I was pretty chagrined, but afterwards it struck me as funny and I’ve been telling the story for years. Living abroad has its challenges, which add a lot of zest to the daily round. Scientists tell us such challenges keep our brains sharp, so I figure I must be at the top of my mental game by now. [Note: For details of other road disasters and embarrassing moments, click on any of the photos below.] Any advice for those considering expat life? Expat life is not a 365-day-a-year vacation. Do your research, and if possible visit several times so you know what to expect — not just about great places to lie in the sun drinking sangria, but in terms of cultural vibrancy, work opportunities, and your particular interests. [To help you get started, click here for the new InterNations poll in which 14,000 expats give their opinions of which destinations you should put at the top of your list.] What do you say to those who equate being an expatriate (someone living outside their own country) with being an ex-patriot (a person who is no longer loyal to their nation)? That’s nonsense. Americans never stay put; on average we move eleven times during our lives, usually to pursue new opportunities. Just as going away to college doesn’t mean you stop loving your parents, living abroad doesn’t mean you stop loving your country. I am a very loyal American. I served my country. I pay my taxes. I always vote. I spend part of every year in the States. But I am also pursuing new opportunities in a larger world. Travel helps me gain fresh perspective — which in my opinion is needed now more than ever. What do you miss most about the USA? Burritos. To me, that’s the taste of America. And what about the future? I consider myself a permanent ambassador of goodwill for our nation. Many people have said, “You two are the first Americans I’ve ever really talked to. You’re not at all what I expected.” And that’s when the conversation gets interesting. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY Be the first to hear the latest about travel, expat life, retiring abroad, and much more!

12 Comments

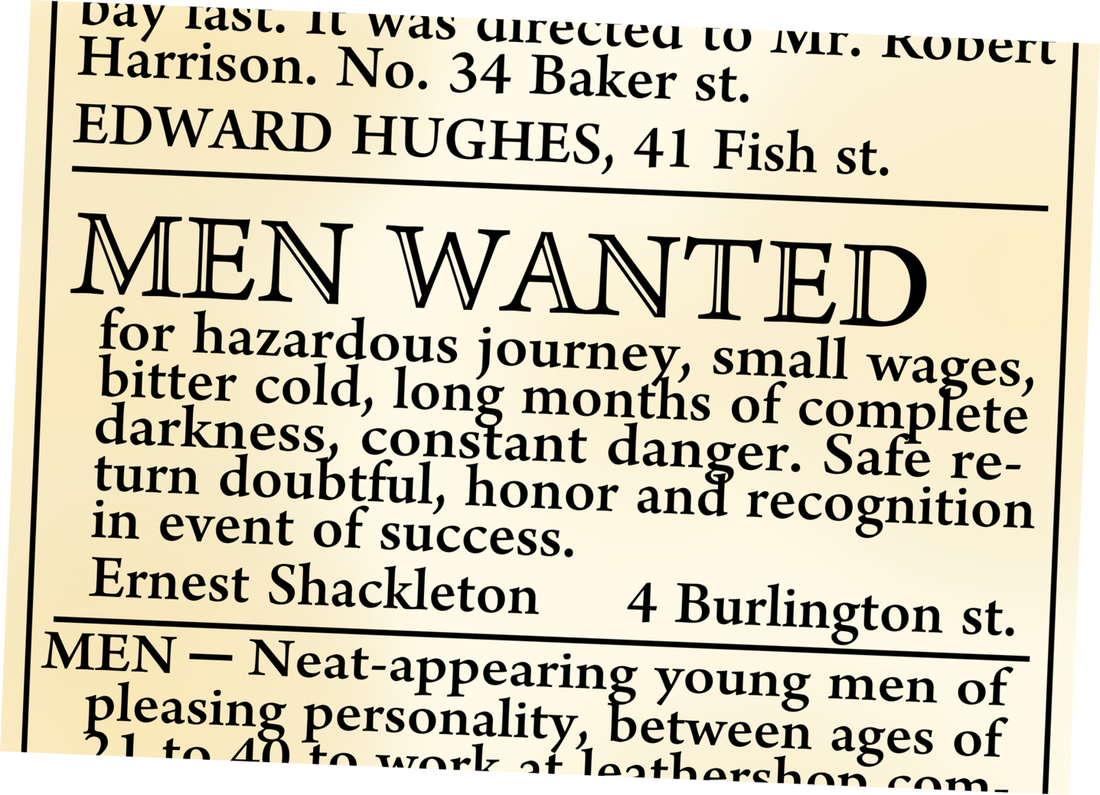

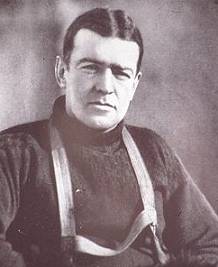

Would you have answered that ad? Me neither, but it allegedly drew 5000 applicants for Ernest Shackleton’s 1914-1917 Antarctic expedition. As it turned out, the ad actually understated the dangers; things went horribly wrong for Shackleton and then they got much, much worse. What was meant to be a triumph — “the last great polar journey of the Heroic Age of Exploration” — became a breathtaking tale of survival against all odds. For starters, Shackleton’s ship, Endurance, became trapped then crushed by the Antarctic ice.  Ernest Shackleton, optimist Ernest Shackleton, optimist The 28-man crew spent five months stranded on ice floes, which eventually drifted close enough to the sea for them to pile into three salvaged lifeboats and sail to a tiny spit of land, the first solid ground they’d set foot on in 497 days. Unfortunately, the spot was well outside of shipping lanes, and by now World War I had broken out; they were 10,000 miles from home and nobody was coming for them. So Shackleton and five crew members set off in a 22-foot lifeboat to sail 800 miles across the most hazardous stretch of ocean in the world. Their goal: a tiny, isolated island with a whaling station. Incredibly they made it, although they landed on the wrong side of the island, so to reach the inhabited part, they had to scale a mountain that was considered impassible. Kind of puts our own vacation disasters into perspective, doesn’t it? I would have given a lot to see the expression on the whalers’ faces when Shackleton and his men walked in to the settlement. It took months to rescue the men left behind, but in spite of all the dangers and hardships, not one single member of Shackleton's crew was lost during the entire expedition. Rich, who is fascinated (OK, obsessed) by the story, took his nose out of the book Endurance long enough to say, “You know what Shackleton said was the single characteristic he looked for in his crew? It wasn’t experience, it wasn’t physical strength, it was optimism.” I was recently reminded of Shackleton and his optimism when I interviewed Lilka Areton at the Museum of International Propaganda. She described how her Czech mother-in-law made it through Auschwitz.  “She never doubted for one single minute that she would survive,” Lilka said. “Her father had sent her to school to learn sewing, and she was put to work doing mending for the Nazi wives. She got her sister and best friend on that work crew, too.” Lilka’s mother-in-law survived her time in the camp and the harsh post-war years under the repressive Soviet-bloc regime that followed. Today, she's in her nineties and living in California. Does optimism really help us survive, or is that an old wives’ tale we cling to for comfort when things go wrong? It turns out optimism really does help us beat the odds, and the benefits are physical as well as psychological. “Do people who see the glass half-full also enjoy better health than gloomy types who see it half-empty?” asked a Harvard Health article. “According to a series of studies from the U.S. and Europe, the answer is yes. Optimism helps people cope with disease and recover from surgery. Even more impressive is the impact of a positive outlook on overall health and longevity. Research tells us that an optimistic outlook early in life can predict better health and a lower rate of death during follow-up periods of 15 to 40 years.” If you’re trying to figure out where you rate on the optimist-pessimists scale, the article explains one way scientists define it. “The pessimist assumes blame for bad news ("It's me"), assumes the situation is stable ("It will last forever"), and has a global impact ("It will affect everything I do"). The optimist, on the other hand, does not assume blame for negative events. Instead, he tends to give himself credit for good news, assume good things will last, and be confident that positive developments will spill over into many areas of his life.” Setting out on any journey demonstrates an astonishing degree of optimism. We are betting our lives that planes really can fly, rental car brakes will work, and food is (mostly) safe to eat. “Optimism is the faith that leads to achievement,” Helen Keller once said. “Nothing can be done without hope and confidence.” My faith in the world suffered a setback this morning when I looked up the wording on Shackleton’s famous ad — the one reproduced everywhere: books, motivational posters, mugs, t-shirts — and discovered it’s likely a myth. Arctic Circle historians have been scouring the Times archives for years without discovering any trace of that advertisement. “Damn it,” I thought. “There goes my lead!” But everything else we’ve read about Shackleton has proved to be true, and in the end, I decided to share the ad anyway. While it may not be the explorer’s own words, it does capture something of his spirit, which he expressed in this (well documented) comment: “Difficulties are just things to overcome, after all.” Words to live by, especially in challenging times. Are you an optimist or a pessimist? How does it affect your ability to overcome obstacles? YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY  Every year, Lola and Rich present the holiday turkey to the assembled guests. Every year, Lola and Rich present the holiday turkey to the assembled guests. “You will never be completely at home again,” said author Miriam Adeney, “because part of your heart always will be elsewhere. That is the price you pay for the richness of loving and knowing people in more than one place.” This is true of nearly everyone I know, especially my fellow Americans; we move an average of eleven times during our lives, leaving family and friends scattered in our wakes from coast to coast — and for the eight million of us living overseas, nation to nation. In interviews I’m often asked, “What is the hardest part of being an expat?” And I always explain that it’s saying goodbye to so many people I hold dear. Going back and forth between the US and Spain involves the sweet sorrow of many partings. And by definition, expats from every nation are inclined to seek geographic solutions to problems with life and jobs. Now there are digital nomads who work over the Internet and move on whenever their 90-day tourist visas expire, exploring the world as they build online careers. All too often, when I’ve met someone congenial and begin to wonder if this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship, my new pal announces she’s moving next week to Switzerland, Vietnam, or New Zealand. When I first arrived in Seville, an American who’d lived there for decades asked how long I was staying, adding honestly, “Because if you’re just here for the short term, I don’t want to get attached!” Back in those early days as an expat, I felt deep confusion over the word “home.” Did it apply to Seville, where I spent most of my time? To California, where I was born and did much of my growing up? To Cleveland, where Rich and I lived for 20 years? I had always thought of home as a physical center point: the base camp from which I explored the world, the kitchen where I cooked Thanksgiving dinner, the cave to which I retreated to lick my wounds when disaster struck in jobs or relationships or world events. Six years ago in Seville, we were hosting Thanksgiving dinner for 20 friends from half a dozen countries, and after dessert, one little girl left the table and ran up and down my hallway shouting, “It’s great to be alive! It’s great to be alive!” And I thought A) she’s right, and B) this truly is home.  Spain meets USA: Rich and Bob, making paella in San Anselmo, CA Spain meets USA: Rich and Bob, making paella in San Anselmo, CA But Rich and I also spend a good chunk of each year, about four months, in San Anselmo, California. We don’t want to become disconnected from our family and friends — or our culture; America is something you have to stay in practice for, and we don’t want to lose our touch. But dividing each year between two places can get confusing. In the early days, I used to feel a faint, nagging disloyalty to my Seville life whenever I referred to San Anselmo as “home.” But the longer I live and travel abroad, the more I realize that going out into the world isn’t about abandoning home, it’s about expanding our definition of it. I have friends who live in gated communities and exist in a state of constant, low-grade fear of everyone outside the walls. It’s as if they had chosen to retreat to a medieval fortress and worried, every time the drawbridge went down, that the guy delivering flowers or the woman coming in to fix the phone lines was a terrorist laying the groundwork for an attack. These friends live in constant, barbarians-at-the-gate vigilance, trusting, it seems, fewer people every year, narrowing their definition of “us” to a very small circle indeed. Getting out and meeting strangers is the best way I know to stop viewing the world through the distorting lens of “us” versus “them.” As Mark Twain put it, “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry and narrowmindedness.” So I count myself lucky to live in two countries and visit so many others in my wanderings. Now, when someone announces an imminent move, I still feel sad that we won’t be hobnobbing in Seville (or San Anselmo) anymore, but I rejoice in the fact that I now have someone to visit in Switzerland, Vietnam, or New Zealand. In dark times, I take comfort from having friends all over the world, thinking of each one as a candle placed in a window, guiding me home. THINKING ABOUT MOVING ABROAD? YOU MIGHT ENJOY

“Closed?” I said incredulously. “But the schedule said ten —“ My friend shrugged. “Apparently it doesn’t open until noon.” “Wait, are you telling me they gave out misinformation? That we didn’t get the straight skinny from these people?” I shook my head in admiration. How subtle! Well played, Museum of International Propaganda. Well played. Arriving back later we found the museum’s doors open and the co-founder, Lilka Areton, in a room filled with dramatic, romanticized images of some of history’s scariest villains. Here were Stalin, Hitler, Kim Il-Sung, and Mao as you’ve never seen them before, surrounded by flowers and sunbeams, holding babies, gazing confidently into a glorious future that somehow failed to materialize. “What inspired you to collect all this?” I asked. “My father was a Marxist,” Lilka told me. “A true believer. He sent me to the Soviet Union in 1960, when I was twenty. I went with a friend, and we toured all around, camping along the way.” She shook her head ruefully. “It wasn’t the paradise my father imagined. I spent the whole time arguing politics with people.” Several years later in New York, she met a young Czechoslovakian named Tom Areton, whose mother survived the Nazi era and time in Auschwitz, then raised her family under the Socialist regime that followed. One of the museum’s exhibits, “On the Porch,” is a painting that hung in the school Tom attended as a boy. It shows a smiling Soviet Red Army colonel surrounded by happy villagers his troops have just liberated from the Germans. What could be more heartwarming than that? After Tom and Lilka married, they moved to Marin County, California and in 1980 launched a non-profit student-exchange program, Cultural Homestay International. It became one of the largest such programs in the world, bringing 12,000 foreign kids to the USA each year. In the course of their work with CHI, the Aretons traveled to 80 countries, collecting political propaganda pieces wherever they went. This year they gathered their best twentieth-century political art and opened the Museum of International Propaganda in San Rafael, just north of San Francisco. The Aretons define propaganda as “the calculated manipulation of information designed to shape public opinion and behavior to predetermined ends . . . Subjectivity, disinformation, exaggeration, and the outright falsification of facts are the hallmarks of propaganda practitioners.” The exhibits are nicely organized and labeled with clarity and flair. For instance, the caption for "Mao Tse-Tung Surrounded by Four Adoring Red Guards" reads, "Just like the statues of the most venerated Saints, Mao is not connecting with his admirers but looks over their heads, other-worldly, into the Communist future.” Of course, while Mao was envisioning a heaven on earth, his policies created an unholy mess that resulted in famine that killed tens of millions of his people. But hey, that’s reality for you. It’s easy to appreciate that kind of irony after the fact and from afar. When Robert Thompson, professor of popular culture at New York’s Syracuse University, visited the museum, he pointed out, “If another country does it, it’s propaganda. If our country does it, it’s patriotism.” He added that these forms of propaganda “are all tapping into the deep emotions that are part of the soul. We still have propaganda that’s operating under the same principles. One can argue that every TV commercial is propaganda.” I don’t think we have to search too far for examples of that during these final days of the run-up to the US presidential election. If being inundated with propaganda teaches us anything, it’s that the key to manipulating people is getting them to abandon rationality in favor of symbolic thinking. When we see a smiling man holding a baby with flowers, our brains are hardwired to assume he’s a decent guy — until we realize that the kindly Uncle Joe in the picture is Joseph Stalin, the ruthless dictator who unleashed the Great Terror that took millions of lives. In a world that continues to be awash with carefully crafted deception, how can we ever hope to know the truth? There’s no easy answer, but here are seven warning signs, drawn from the museum’s exhibit categories, that should spark a ping from our internal falsehood-seeking radar:

And now, in the spirit of full disclosure, I want to admit that I was wrong. I checked the museum’s visiting hours in the final days of October and arrived there on November 2, just after the new winter schedule shifted the opening time to noon. This revelation may not be earth-shattering or worthy of a painting with flowers and sunbeams, but whew! I feel better having removed one tiny untruth from the world. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|