|

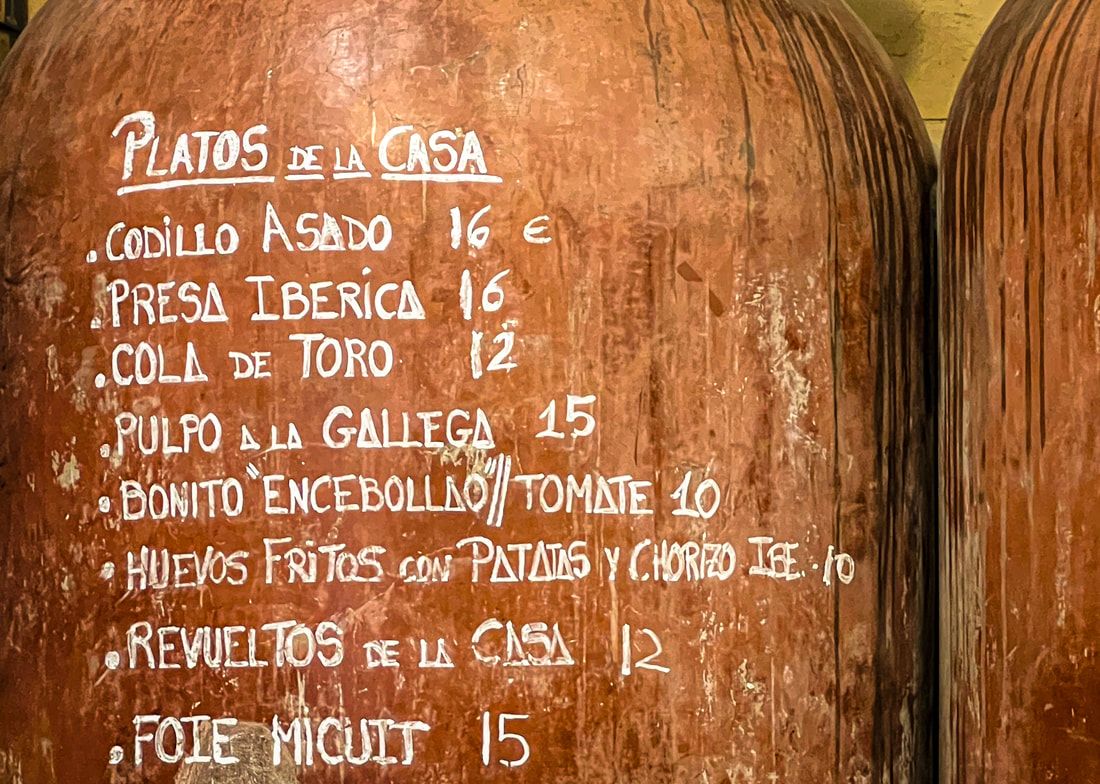

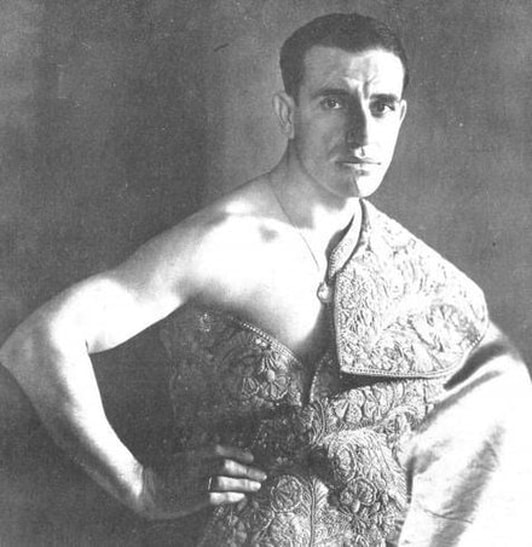

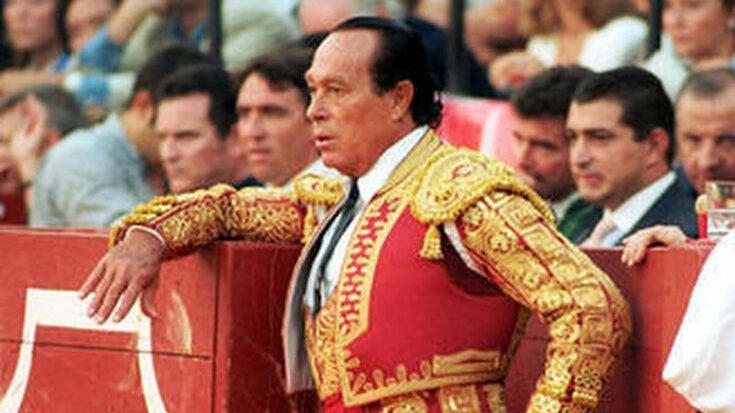

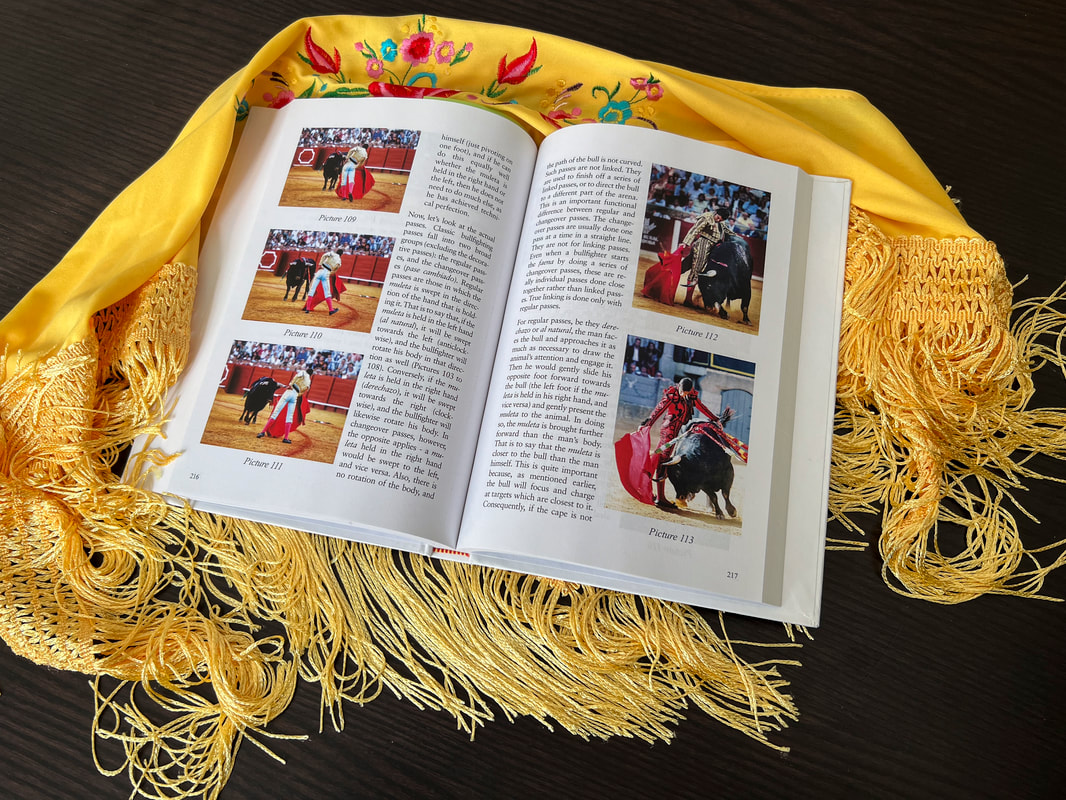

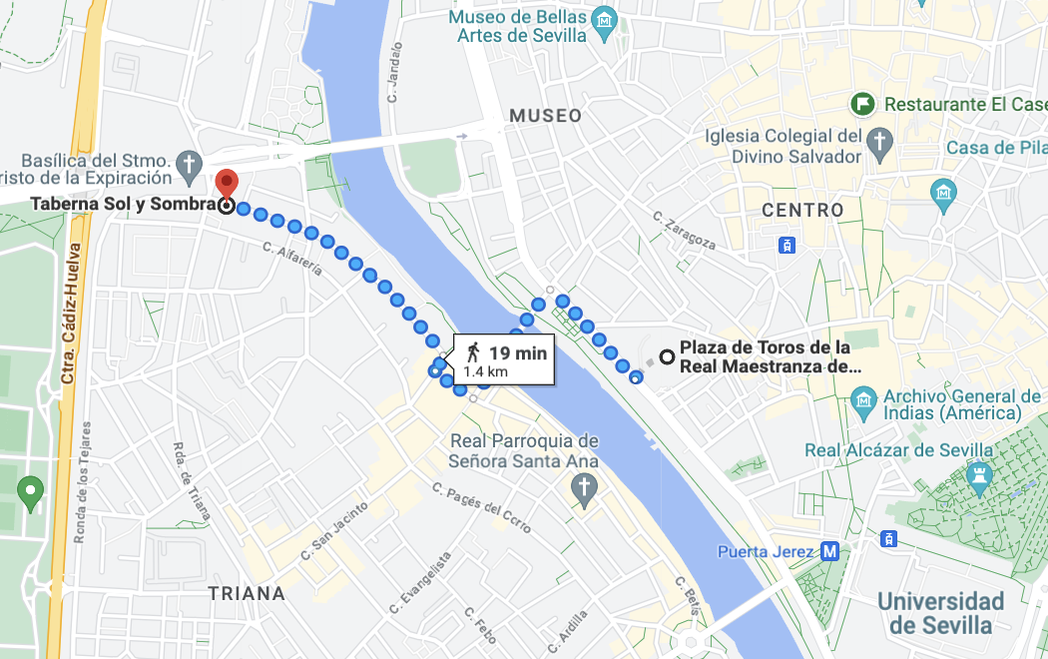

When I was laid low with a cold last week (I'm fine now, thanks for asking) I found myself watching lots of WWII videos to cheer myself up. First of all (spoiler alert!) we always win in the end. And while I might have been coughing, sneezing, and blowing my nose every 15 seconds, at least nobody was shooting at me or reducing my city to rubble. Also, I didn’t have to answer unthinkable questions like “So …. shall we build an atomic bomb or let the Nazis do it first?” Nor did I have to worry about defending my virtue. In Atlantic Crossing, Crown Princess Märtha of Norway, desperate to get America to join the Allies, spent much of WWII being chased around Washington, DC by that old womanizer, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who never let little things like being married or in a wheelchair slow him down. It was impossible to watch without asking myself, “Just how far would I be willing to go to save my country, Europe, and civilization as we know it?” One of the reasons we go to the movies — and spend sick days on the couch in front of the TV — is to imagine, if only briefly, how we would face up to life’s tough challenges. It’s why American teenagers flock to horror movies, millions of adults are addicted to reality TV and extreme sports, and why bullfighting has been popular for 4000 years. Especially in Seville. When I first came to Seville, I was gobsmacked to see all the bullfighting memorabilia around here. Gigantic horned heads loom high on hotel walls, glittering trajes de luces (bullfighters’ “suits of light”) gleam in restaurant display cases, and flyspecked black-and-white newspaper photos of famous toreros hang in places of honor above even the humblest bar. Animals killed in the ring are always eaten, appearing on menus as cola de toro, a succulent stew of bull’s tail simmered in wine and herbs. Years ago Antonio, owner of a tiny neighborhood tavern in the Triana district, tacked to his wall a newspaper clipping with the headline, “¡Volveré a torear!” (“I will return to bullfighting!”) When I asked about it, he explained that for his debut in Seville, one bullfighter decided to make his mark and demonstrate his courage by dropping to his knees and holding his ground when the bull was released into the ring. The bull, hardly able to believe his luck, instantly lowered his head and gored the man’s chest, neck and face. Antonio, Rich, and I gazed at the hideous scars in the grainy newspaper picture. “Where is this man now?” I asked. “Working in a stationary store here in Triana,” Antonio said. So much for that career in the bullring. Rich and I were reminiscing about that ex-bullfighter (whose name has been so lost to history I couldn’t even track him down on Google) during a recent lunch at Sol y Sombra, a classic bar taurino (bullfighting bar) in the Triana district. Sol y Sombra is dim and cozy, with worn tiles, yellowed posters, and handwritten menu cards stapled to the walls. Rolls of toilet paper are scattered about, to be used in place of napkins. Just keeping it humble and real. Faces of top toreros peer down from every wall. Many of them are unlikely characters, such as Juan Belmonte, a spindly Trianero with crooked legs. "My legs were in such a state," he said, "that if one wanted to move, it had to request permission from the other." Unable to leap nimbly out of harm’s way, he had to find another way to fight. "At night," he said, "we would swim the Guadalquivir and fight the bulls in the pastures in the moonlight. That was the beautiful time, fighting them naked in the moonlight." Naked or clothed, he developed a unique, close-in, barely moving style that led to getting gored fifty times but won him acclaim as “the greatest bullfighter of all time.” Another unlikely local hero is Curro Romero, who often took fright and ran away from a bull, flapping his cape from a safe distance, not even pretending to fight. “Curro was booed and cursed and rained on with seat cushions,” explained blogger 100swallows, “and of course fined heavily for breaking the rules that required a bullfighter to kill his animal.” But when he was at his best “it was like going to heaven. There was nothing like it in this world. If you saw it, you knew you had seen something angelic. Curro hypnotized with his slow capework and the dignity of his poise. The bull charged as though he too were trying with all his might to reach perfection, to ‘get it right.’” Say what you will about bullfighting — go ahead, everyone does! — you have to admit it’s colorful stuff. The season starts Easter Sunday, runs through spring, pauses during the heat of summer, and finishes up with a few fall events. And I can already hear you thinking, “Nope, not me! I wouldn't be caught dead at a bullfight!” Never say never. When my friend Reza Hosseinpour, the brilliant pediatric heart surgeon, moved to Seville, he was appalled by the very idea of bullfighting. But Spanish amigos finally persuaded him to go just once, and he fell in love with “the esoteric ritualistic art.” Eventually he wrote the first comprehensive English book on the subject, the meticulously researched and lavishly illustrated Making Sense of Bullfighting. Inspired by our lunch at Sol y Sombra, Rich and I decided to drop by Seville’s Maestranza bullring. During the off hours you can pay a small fee and wander about to your heart’s content, checking out the museum, the arena, and the torero's chapel, where some of the most urgent praying on Earth takes place. When I first visited you could also poke around in the bullfighter’s hospital — another hotspot for communing with the Almighty — but then some stickler for hygiene objected to the idea of random crowds tramping around a sterile operating theater, and the medical facility was shifted to a less public area. Go figure. The museum houses a wonderful collection of trajes de luces, some still showing bloodstains. Toreros are “dressed to kill” in outfits inspired by the spangled, embroidered, and tasseled extravagances favored by dandies in the eighteenth century, when modern bullfighting practices developed. To prevent horns from snagging in the fabric, the fit is super snug. Indeed, men wear their trousers so tight that their “noble parts” are clearly visible, arranged to one side, or “away from the bull,” as famously demonstrated in this statue of Curro Romero. Life is full of impossible moral dilemmas. Should animals be killed for food? If so, is it wrong to perform this act yourself, assuming personal risk to achieve artistry? Is it kinder to raise beasts in overcrowded pens and kill them in slaughterhouses ringing with the death cries of their mates? Is it OK to eat cola de toro if you’re opposed to bullfighting? These questions have been hotly debated for thousands of years, and are best discussed over a cold beer in one of Seville’s classic bullfighting bars. Let me know what you decide. BULL BARS YOU MIGHT LIKE Taberna Sol y Sombra, Calle Castilla, 147, Triana Casa Pepe Hillo, Calle Adriano, 24, Seville centro Bar Estrella, Calle Estrella 3, Seville centro OUT TO LUNCH This story is part of my ongoing series "Out to Lunch." Each week I write about visiting offbeat places in the city and province of Seville, often by train, seeking cultural curiosities and great eats. (Learn more.) WANT TO STAY IN THE LOOP? If you haven't already, take a moment to subscribe so you'll receive notices when I publish my weekly posts. Just send me an email and I'll take it from there. [email protected] LIKE TO READ BOOKS? Be sure to check out my best selling travel memoirs & guide books here. PLANNING A TRIP? Enter any destination or topic, such as packing light or road food, in the search box below. If I've written about it, you'll find it. Why is Rich carrying around a bull's head?

Read all about it here.

16 Comments

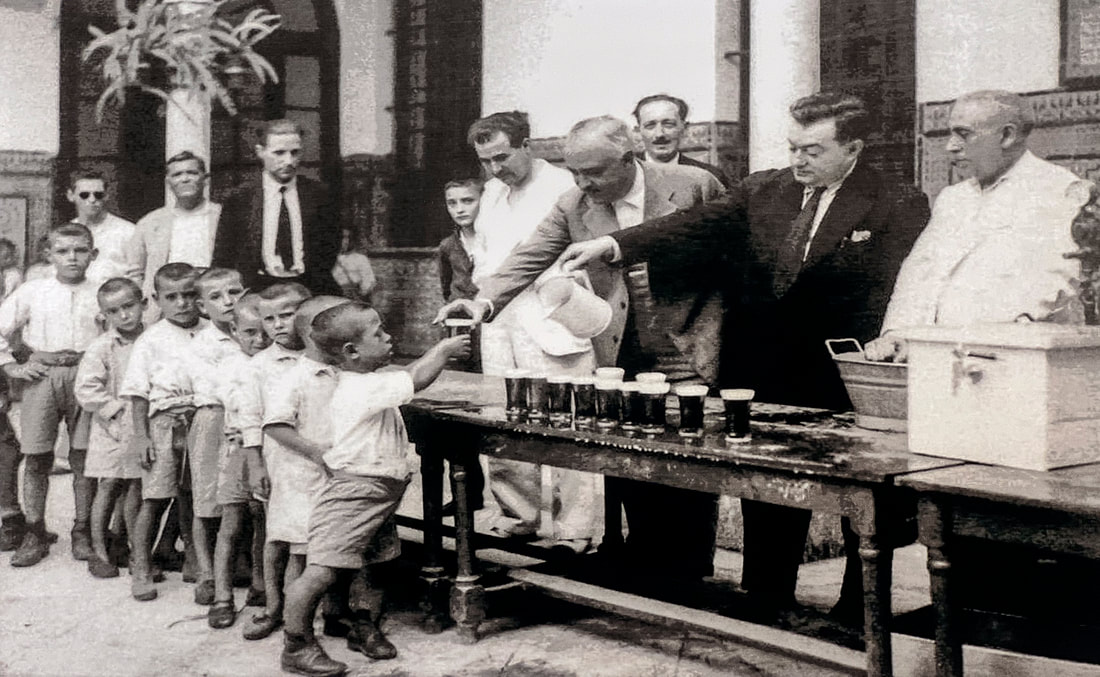

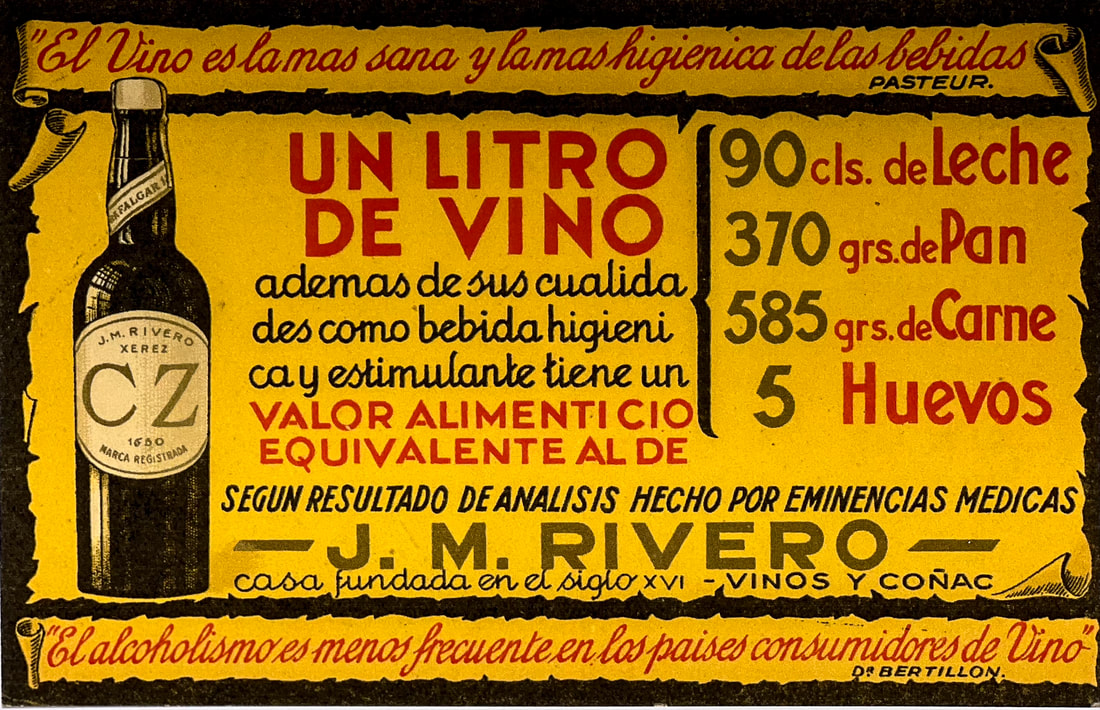

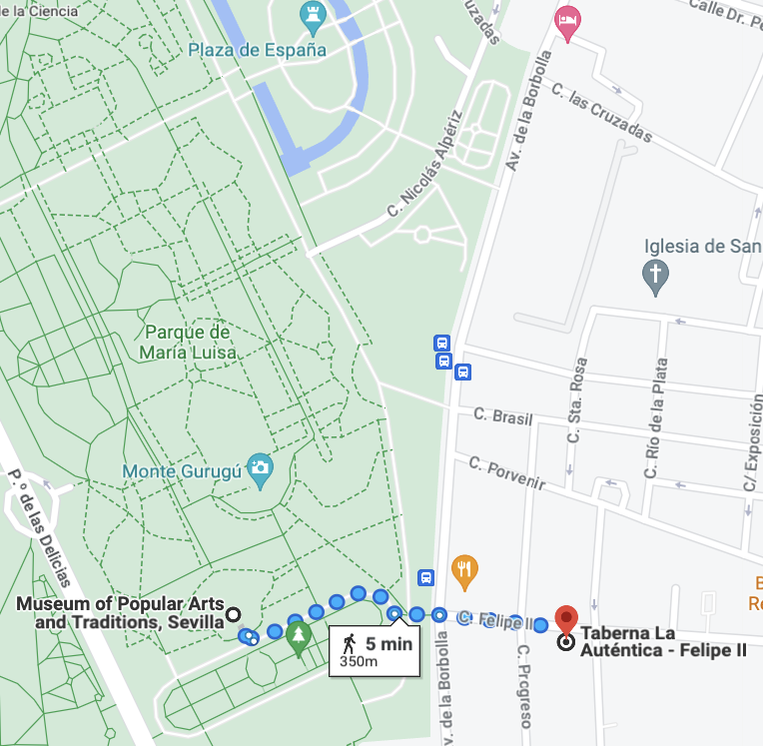

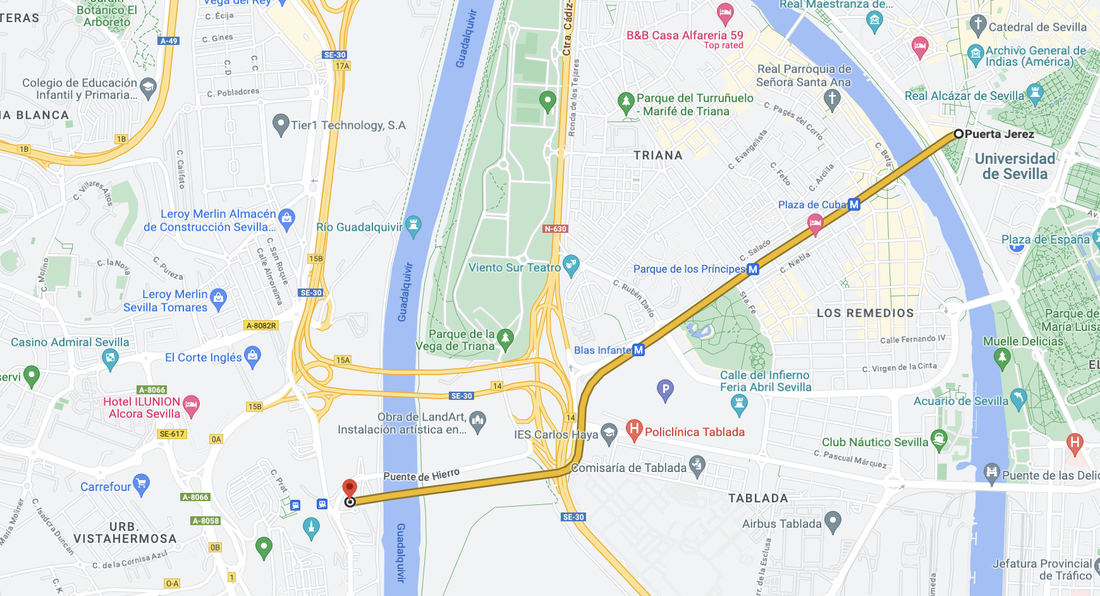

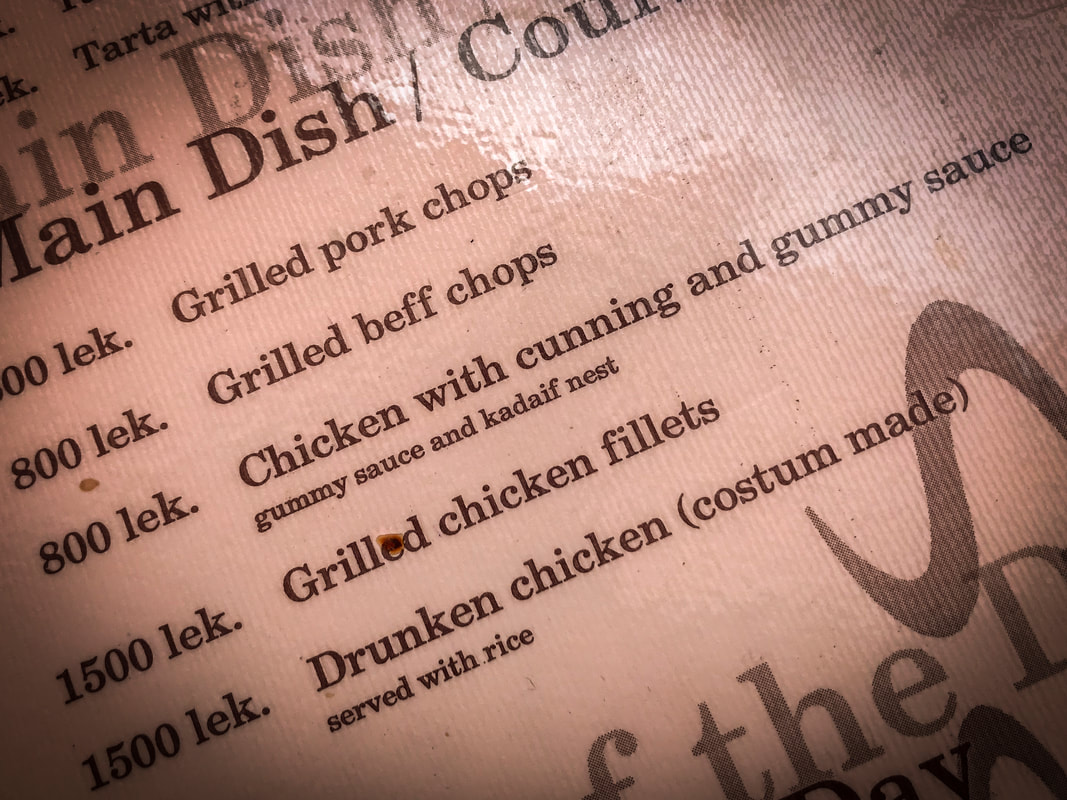

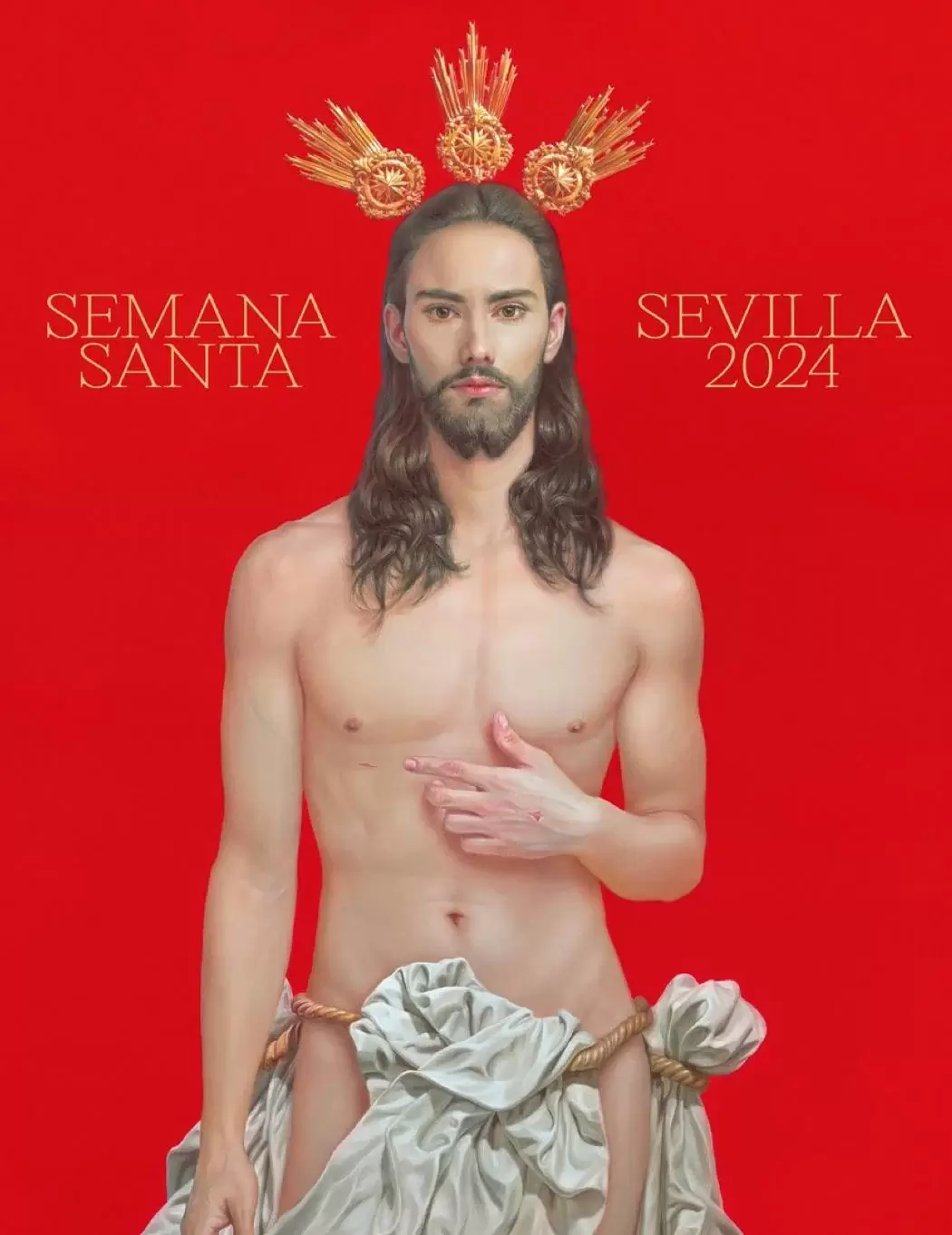

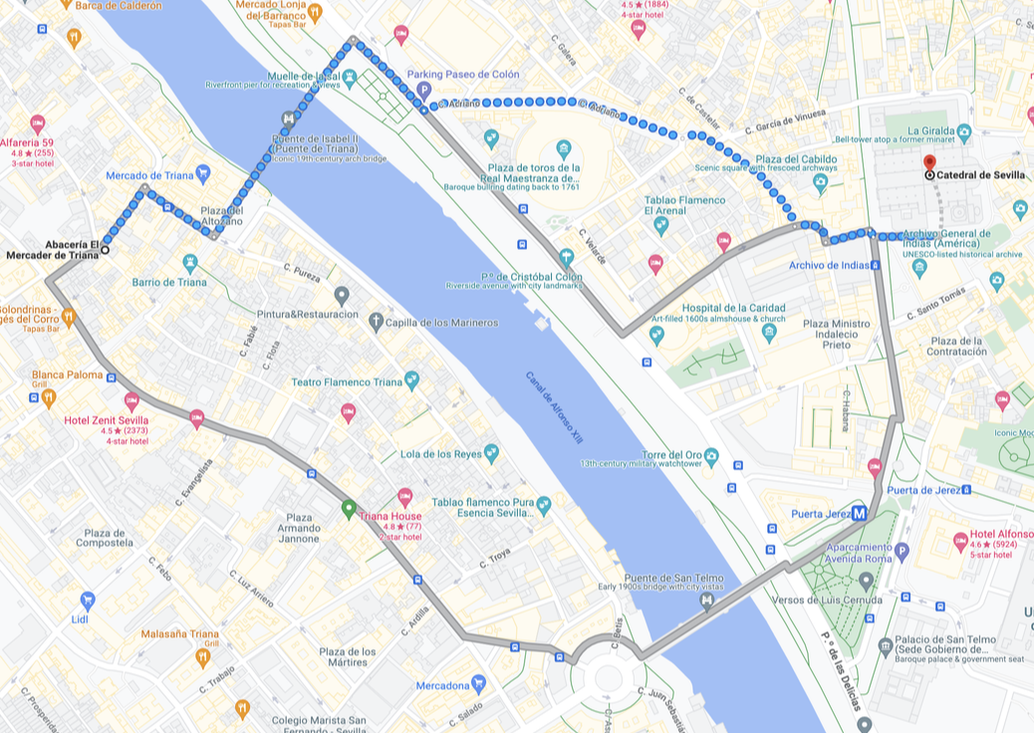

Hot news! Time travel is real — and I have proof! How else would you explain this recent email, asking me to remove a subscriber: Hello, I have retired from Washington University as of 5/3/21021. For assistance with microarray-related research, please contact the following staff … Observe the facts, Watson. 1) She retired in 21,021, some 18,997 years in the future. 2) She’s a scientist. 3) I couldn’t find her anywhere on my mailing list (maybe she hasn’t subscribed yet?). 4) Her university sponsors a hot air balloon called “Time Traveler.” Coincidence? Oh sure, think that if you want. Of course, until this former/future reader of mine shares her scientific breakthroughs, my only form of time travel is immersing myself in the past. This week, Rich and I spent many entertaining hours reliving bygone days in the Museo de Artes y Costumbres Populares de Sevilla (the Museum of Popular Arts and Customs of Seville). Never heard of it? You’re not alone. It’s one of the city’s best-kept secrets. Housed in a vast, four-story 1914 exhibition hall in Maria Luisa Park, the museum has chosen, inexplicably, to bury its permanent collection in the basement. Wandering the subterranean labyrinth, you get a glimpse of daily life and age-old wisdom that sparks profound, thought-provoking questions, such as: how do you encourage small children to drink more beer? It takes a village. The heartwarming 1933 news photo above shows officials holding a beer tasting session for young orphans at a health center in Seville’s Triana district. Just helping them get their start. You see, until the 1960s, beer wasn't all that popular in Spain. For 3,000 years wine had been the beverage of choice, viewed as a vital part of a wholesome diet. The 1850 Trafalgar Wine ad below favorably compares vino’s nutritional value to that of bread, milk, meat, and eggs, and quotes Pasteur as saying "Wine is the healthiest and most hygienic of beverages." “Until quite recently,” explained a museum display, “men, women, and children drank wine throughout the day. They watered it down, spiced and flavored it, and customarily ate bread dipped in wine for breakfast. Even medical professionals considered it just another form of nutrition, and the calories it provided were deemed essential to the poor diets of the underprivileged classes. Other factors contributed to these ideas and habits: the unpleasant taste and bad reputation of water … and the unpopularity of beer, which was only brewed in northern Europe.” But as we all learned in college, it’s not very hard to convince people to drink beer. Seville established its brewery, Cruzcampo, in 1904 and spent much of the twentieth century campaigning for young hearts and minds. But of course, children need more than beer to grow up big and strong, and for a long time the museum presented another exhibit — now removed to keep tourists from fainting — about la matanza. This is the winter pig killing, when the entire village gets together to butcher a 500-pound animal, keeping everyone fed until spring. The museum’s small, grainy, black-and-white video of the matanza was hair-raising. It showed the killing, the butchering, and the village grandmothers cleaning out the intestines to make sausage casings — a process, I’m told, that is traditionally enlivened by the women’s bawdy jokes. Sadly, the video had no sound, so I can’t share any. Even without the matanza video, there was plenty to see. On display were once-cherished possessions from the last two centuries, including kitchen utensils, toys, and beautifully handcrafted, worn-to-fit-the-palm tools that made Rich drool with envy. It was unnerving to realize how many of these historical objects I’d seen in daily use. The tailor shop, for instance, was just like one that used to be around the corner from our Seville apartment. Rich often gazed through its window, fantasizing about having a bespoke suit fashioned by the elderly proprietor. It closed years ago, and now Rich stood regarding the tailor display with the same wistful look. As for me, an old-style coal-heated brasero (brazier) sparked recollections of visiting a friend’s country home where she announced after lunch that we’d all siesta at a mesa camilla, a round table with a brasero underneath. Ensconced in comfy armchairs, a heavy tablecloth draped over our laps, our feet warm in the chilly room, we all began to doze off — until our host began to snore like a freight train. Our long ramble down memory lane left us with a keen appetite for old-fashioned, homesytle cooking. Leaving Maria Luisa Park, we started up Calle Felipe II, a broad street where good neighborhood eateries appear with cheering frequency. We soon settled on Taberna La Auténtica, a roomy tapas bar that’s particularly gifted at crafting tortillas. Decades ago, I was stunned to discover that here, a tortilla isn’t anything like the flatbread we Californians wrap around our tacos and burritos. The name means “little cake,” and in Spain, it refers to a dense potato omelet, often called tortilla española or tortilla de patatas to avoid confusion. Debate continues to rage about whether to include onions; fortunately for me, Seville is firmly in favor and so am I. One bite and tortilla became my go-to comfort food, a tapa I can enjoy any hour or the day or night. The secret lies in the texture, dense yet tender; this requires plenty of oil (dos dedos, or two fingers deep, is the standard measure) and low-temperature cooking. The real challenge comes when you have to flip it halfway through, either sliding it onto a plate or using one of the newfangled hinged double pans (which many regard as cheating). My one attempt to make a Spanish tortilla, even with coaching from two local women, resulted in disaster: a burnt exterior and runny interior, although to be fair at least 10% of it was marginally edible. Some cooks are famous for creating tortillas five inches thick, and frankly, my sombrero is off to them. The customary height is about half that, served in a pie-like wedge, sometimes with a side of mayo or drizzled with whiskey sauce. Food trends constantly evolve. You’ll be relieved to hear Sevillano kids are no longer raised on beer and wine, although they are allowed the occasional taste from a young age, and teens often gather on weekends to imbibe (hard to imagine, I know). Villages still hold matanzas, although some are now turning the job over to professionals, and many say their social life and store of bawdy jokes are the poorer for that. The tortilla is as popular as ever and likely to remain so well beyond the year 21,021. If the past has taught us anything, it’s to take nothing for granted, not even our most cherished beliefs. Just look at all those conscientious parents who gave kids sips of wine all day or told them beer was the breakfast of champions. If we’re lucky, we live and learn from our individual and collective missteps. As the old Spanish proverb puts it, "A wise man changes his mind, a fool never will." STORIES ABOUT SOME OF MY OTHER FAVORITE MUSEUMS Museo de Bellas Artes (Fine Arts Museum), Seville Bigfoot Discovery Museum, Santa Cruz, CA Museum of Failure, Traveling Exhibitions Atomic Bunker Museum, Kaunas, Lithuania The Empathy Museum, Traveling Exhibitions OUT TO LUNCH This story is part of my ongoing series "Out to Lunch." Each week I write about visiting offbeat places in the city and province of Seville, often by train, seeking cultural curiosities and great eats. (Learn more.) WANT TO STAY IN THE LOOP? If you haven't already, take a moment to subscribe so you'll receive notices when I publish my weekly posts. Just send me an email and I'll take it from there. [email protected] LIKE TO READ BOOKS? Be sure to check out my best selling travel memoirs & guide books here. PLANNING A TRIP? Enter any destination or topic, such as packing light or road food, in the search box below. If I've written about it, you'll find it. When I explained to the hospital emergency staff that my American visitor had a piece of his hearing aid stuck in his ear, the three white-coated professionals erupted into gales of laughter. And so did my friend, saying, “Hey, it’s not funny,” as he chuckled along with them. And this is what I love about the Spanish medical system — in fact, about the entire Spanish culture. Being a professional doesn’t seem to require the same kind of emotional distance that’s customary in the US. In fact, people talk to each other all the time in situations that astonish me. Last Saturday, when Rich and I were in the Metro waiting for a train, a woman plopped down beside us and said, "¿Qué tal la lluvia de ayer?" (“How about that rain yesterday?”) As we chatted about the downpour, I tried to imagine someone in the New York subway or a San Francisco BART station making eye contact, let alone conversation. Clearly a wildly different social etiquette prevails in Seville Metro. But then, the Metro is a funky little transit system running just 11 miles; it feels remarkably safe — unless you suffer from bathophobia (the fear of depths). Apparently the engineers kept running into more layers of ancient ruins and had to burrow deeper and deeper underground. As I stepped off the fourth long escalator, I said to Rich, “I’m not sure, but I think I can actually feel the earth’s molten core beneath my feet.” Our journey into the Metro underworld was prompted by the death of the battery on Rich’s power drill. As Rich learned during an exhaustive, city-wide search, battery design has advanced considerably over the past 17 years, and the one he needed no longer exists. He was forced to lay his faithful drill to rest and start thinking about a replacement. To cheer him up, I suggested we head out to Leroy Merlin, the giant, French-owned home improvement store in the nearby suburb of Tomares. We’d make a day of it, buying a drill then going for a pleasant browse around the adjacent poligano, four square blocks of discount houses selling furnishings ranging from practical to whimsical. To make it blog-worthy, we’d lunch at a workers’ café we liked. A lovely outing all around. And then, hours before departure, I discovered what Leroy Merlin has been up to in Russia. Leroy Merlin reacted to the invasion of Ukraine by doubling down on its loyalty to Moscow. It cut loose its Ukraine branch, agreed to donate money and supplies to Putin’s war effort, and committed to helping the government conscript Leroy Merlin employees to serve in the Russian army. In July, Leroy Merlin (along with Unilever and Proctor & Gamble, who did likewise) was named "an international sponsor of war" by the Ukrainian government — admittedly not an objective third party, but still. “Rich, I have bad news about Leroy Merlin,” I said. The price of a drill was obviously not going to tip the balance of geopolitical power, but we felt uncomfortable swelling the coffers of a war sponsor even by that minuscule amount. Knowing Rich had always regarded the megastore as something of a temple, I added, “I’m sorry for your loss.” On the plus side, I’d learned something extraordinary about Tomares: it’s the richest town in Andalucía. “Let’s go anyway,” I suggested. “Obviously we’ll avoid the megastore-that-shall-not-be-named, but we can visit the poligano and then walk up the hill to see what the main town is like.” After the short Metro ride, we strolled to the poligano, enjoyed a coffee in the workers’ café, and visited the shops, which had lost none of their zany, treasure-hunt feel. I was only sorry we didn’t need an antique bed, bicycle-shaped table, or plastic meerkat. Leaving the poligano for the town proper, the first thing we saw was the Casino Admiral, home to 100 slot machines, electronic bingo, American roulette, and shows featuring Spanish comedians and Queen tribute bands. We didn’t stop. I soon began noticing small children running around in costumes. Then we walked smack into the tail end of a parade, and I realized Tomares was celebrating Carnival. This is the age-old “farewell to meat” party that marks the beginning of fasting during Lent, the 40-day run-up to Easter. The idea of Carnival is to overindulge while you still can, and it was clear from the overflowing taverns that the townspeople were really prepared to put their backs into it. The sunny day began to darken, the wind picked up, and a sudden rainsquall sent us dashing into the nearest shelter, which happened to be Bar Tipitin’s enclosed terrace. The owner kindly shoved some reserved tables closer together to create a small space for us, tucking our table cozily next to a heater. Explaining there was no printed menu, he began a serious discussion about the various meats he was grilling on the barbecue a few yards away. The smell was heaven. “Pluma,” Rich said decisively. That means feather, although it’s anything but light; this cut comes from the back of the pig’s neck and is famous for its rich fat and superb flavor. Soon our host returned with a platter displaying a large slab of raw pork for our inspection. Before I could say, “Do you have anything smaller?” Rich said, “Sí, perfecto.” Forty years together, twenty of them in Spain, and I’d never seen Rich order pluma or a piece of meat that massive. It was nice to know he could still surprise me. The pluma was magnificent, sizzling hot, perfectly cooked, and dusted with just the right amount of coarse salt. After I’d cut off the small corner that was my preferred portion, Rich proceeded to eat the entire rest of the piece, surprising me again. The man may not own a functioning power drill, but he does possess, as the Spanish put it, “una buena boca,” literally a good mouth, meaning a splendid appetite. He wasn’t alone. Everyone was tucking into platters of grilled meat with similar gusto, and I marveled yet again about cultural differences. Having grown up in what’s now Silicon Valley, I associate affluence with slim, gym-toned bodies clothed in upscale fashions. This being an agricultural area, folks tended to enjoy robust figures, weather-beaten faces, and a merciful lack of trendiness. Most looked like they could bench-press a tractor and would enjoy a good laugh if someone had to have a hearing aid surgically removed from an orifice. It was a wonderful day, even if we didn’t come home with a power drill. I’ve since learned that Leroy Merlin has yielded to public pressure and sold off 99.993% of its Russian business to a firm from the United Arab Emirates. A step in the right direction but a bit late to keep us as customers. And so the quest for a new power drill continues. I’ll keep you posted on our progress. Read About Our Time in Ukraine We visited before the war and fell in love with the zany humor and remarkable grit of the Ukrainian people. Learn more OUT TO LUNCH This story is part of my ongoing series "Out to Lunch." Each week I write about visiting offbeat places in the city and province of Seville, often by train, seeking cultural curiosities and great eats. (Learn more.) WANT TO STAY IN THE LOOP? If you haven't already, take a moment to subscribe so you'll receive notices when I publish my weekly posts. Just send me an email and I'll take it from there. [email protected] LIKE TO READ BOOKS? Be sure to check out my best selling travel memoirs & guide books here. PLANNING A TRIP? Enter any destination or topic, such as packing light or road food, in the search box below. If I've written about it, you'll find it. I often see newcomers blinking in confusion over Seville menus offering “lard of heaven” (the eggy dessert tocino de cielo) or “green Jews” (a mistranslation of judías verdes, meaning “green beans”). But generally Spanish restaurants describe their dishes with admirable clarity, and we are spared the kind of pretentious nonsense that’s all too familiar elsewhere. “Here, for example,” wrote author Peter Mayle, “is a London restaurant’s attempt to justify the exorbitant price of its whitebait: ‘The tiny fresh fish are tossed by our chef for a few fleeting seconds into a bath of boiling oil, and then are removed before they have a chance to recover from their surprise.’ Anyone who suggests tossing the writer in after them has my full support.” You expect that kind of silliness in London or Albania, but not Seville. So it took me a few moments to recover from my surprise when I picked up a café menu this week and read: “The Hake Has Balls and the Squid is Downright Saucy!!” Yikes! Did I want fish balls topped with cheeky squid? No, I really didn't. Soldiering on, I discovered a dish called “What Have I Done to Deserve This,” pork brioche in a sauce of “coke and wine.” Would that be Coca-Cola or cocaine? Further down was “pastor meat,” denomination unspecified. As a writer, I had to admire the author’s daring, even while I questioned some (ok, most) of the word choices, which sounded equally bizarre in the Spanish version of the menu. I reminded myself this was Seville’s Triana district, which for millennia was a notoriously independent separate city, home to outliers, misfits, flamenco dancers, scallywags, bullfighters, and artists. Technically it’s now part of Seville, but clearly Triana is maintaining its reputation for ignoring the rules and living out loud. Triana is also justly famous for the excellence of its mud. The blue clay lining the Guadalquivir River is ideal for making ceramics, a fact noted by the crafty Romans back in Biblical times. They developed an artisan community that has provided a hundred generations of Seville families with plates, cups, platters, and statues of various deities. And of course, where you have deities, you have controversies. One such controversy involved early Christian potters, sisters Justa and Rufina, who refused to sell their wares for use in pagan rituals. Angry neighbors attacked their stall, and in the ensuing donnybrook, one of the sisters broke a statue of Venus. The two potters were arrested, jailed, tortured; Justa died first. Rufina was then thrown to the lions, but the beasts became as tame as kittens, licking her feet. (It’s possible some of these details may not be 100% accurate.) Rufina was eventually beheaded, and the sisters became Seville’s patron saints, always shown with piles of pottery at their feet. Triana’s pottery really upped its game in the seventh century when the Moors conquered the region. The new overlords brought with them sophisticated techniques such as white tin-glazing and the iridescent gold finish known as lusterware, adding breathtaking dazzle to local architecture and housewares. Another game-changer was the arrival of British aristocrat and entrepreneur Charles Pickman in 1841. Looking to build a factory, he bought Triana’s ancient Cartuja Monastery, where Christopher Columbus had prepared for his voyage to the New World and later the artist Zurbarán painted some of his best-loved masterpieces. At first Pickman’s factory was welcomed as a revitalizing force in the industry and a source of jobs, but the elegant English designs — and higher prices — soon stirred up resentments. Competitors reacted by embracing pre-industrial techniques and old-school Spanish designs, an approach that lasted well into the twentieth century. By the 1970s, Triana’s ancient, wood-fired kilns were creating so much smoke pollution that they were banned, marking the beginning of the end of large-scale commercial pottery production in the barrio. You can still see some of the ancient kilns in the rambling, fascinating Centro Cerámica Triana museum. Pickman's Cartuja Ceramics moved to a neaby town in 1982, and today the monastery serves as the Andalucía Contemporary Art Center, home to some outrageous art. No discussion of outrageous contemporary art in Seville would be complete without a mention of the red hot controversy currently convulsing this city. Every year officials commission a poster to promote Semana Santa (pre-Easter Holy Week) when the streets are jammed with processions and visitors. Typically posters show pious depictions of the suffering Jesus, a weeping Mary, or an adorable altar boy. This year’s theme is the risen Christ. Luminous, radiant, and absolutely gorgeous. Every one of the powerful Holy Week organizers, the Council of Brotherhoods of Seville, signed off on the piece before last week’s unveiling. Ultra-conservatives took one look and began foaming at the mouth, cursing the day it became illegal to burn heretics at the stake. Death threats have been hurled at the artist, Salustiano Garcia, who said, “To see sexuality in my image of Christ, you must be mad,” adding there was nothing in the image that “has not already been represented in artworks dating back hundreds of years.” Curious yet? Want to see what all the fuss is about? Yowser! People will be talking about this poster for centuries. Which is no doubt why they did it. “Contemporary art challenges us,” said billionaire collector Eli Broad. “It broadens our horizons. It asks us to think beyond the limits of conventional wisdom.” Art is all about redefining what it means to be alive in a particular era. We have to keep at this, because we humans are ceaselessly reinventing ourselves and our environments. And that’s what’s happening right now in Triana’s old ceramic district, where they’re busy dismantling the last vestiges of a 2000-year-old industry. Artisans still make pottery in small workshops, but the big factories are being transformed into stores, restaurants, wine bars, and abacerías, tiny grocery markets with a few café tables and, in most cases, modest menus. The Abacería El Mercader de Triana, however, went large with a flamboyant bill of fare, placed temptingly on tables set beneath orange trees on a back street winding past the former ceramic factories. I sat down and began reading, curious to see how our host proposed to “reanimate” (as the Sevillanos say) weary wayfarers like ourselves. “Listen to this,” I said to Rich. “There’s one called ‘Does Not “Entrail” Any Risk.' Apparently it’s a plate of entrails with chimichurri sauce. Yikes!” I'm not a bashful eater, but in the end I selected the more conventional “A Sword That Doesn’t Kill,” tender swordfish steak lounging on a bed of lively lime-infused potato-ginger puree. I reflected that Sevillanos, once the most conservative of eaters, had come a long way in the twenty-plus years I’d been hanging around with them. The city continues to draw its strength from ancient traditions — culinary, spiritual, artistic, and social — yet fearlessly embraces fresh ideas that even the most modernist thinkers might find startling. And that’s why I never take this city for granted; I’m always agog to see what’s going to happen next. OUT TO LUNCH This story is part of my ongoing series "Out to Lunch." Each week I write about visiting offbeat places in the city and province of Seville, often by train, seeking cultural curiosities and great eats. (Learn more.) WANT TO STAY IN THE LOOP? If you haven't already, take a moment to subscribe so you'll receive notices when I publish my weekly posts. Just send me an email and I'll take it from there. [email protected] LIKE TO READ BOOKS? Be sure to check out my best selling travel memoirs & guide books here. PLANNING A TRIP? Enter any destination or topic, such as packing light or road food, in the search box below. If I've written about it, you'll find it. |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|