|

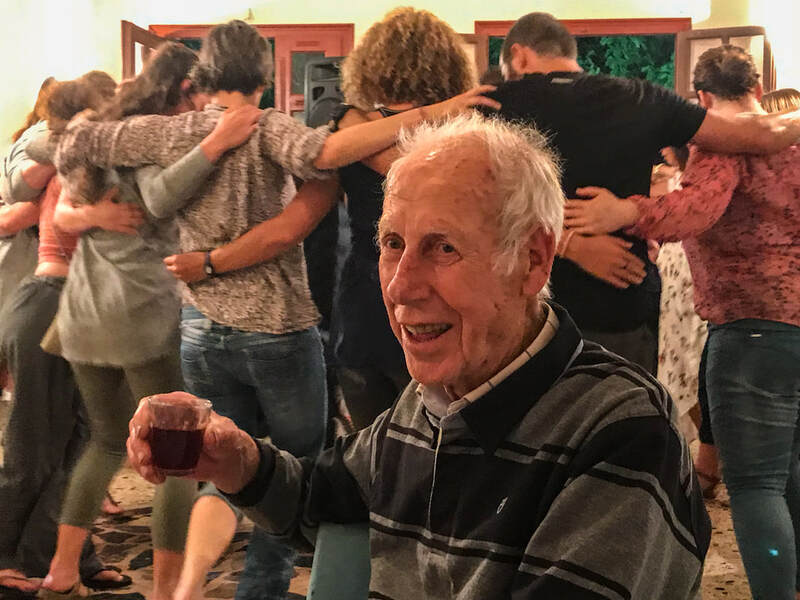

“Look at this island! People there live longer and healthier than just about anywhere. We should go. Maybe it will rub off on us,” I said to Rich a few years ago, while researching our Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour. “They did a study and 80% of the men between 65 and 100 still enjoy an active sex life.” Impressively, these guys still had plenty of energy leftover to get out on the dance floor as well. The island was Ikaria, Greece, one of the Blue Zones, regions famous for vitality and longevity. I went to an all-night party there, and the 93-year-old who opened the dancing was still at it when Rich and I stumbled out the door in the small hours of the morning. Yowza! There's a famous story about one island resident's powers of recovery. Several people on Ikaria told me the tale, and Dan Beuttner wrote about it in The Blue Zones. During WWII, a young Ikarian named Stamatis Moraitis had an injury that required treatment in the USA. He stayed there, married, and raised a family. At 60 he learned he had lung cancer; his five doctors gave him six to nine months to live. He decided to go back to the island so he could die among his own people; he and his wife moved in with his parents, and Moraitis retired to bed to await the inevitable. Old friends dropped by to share a glass of wine. Occasionally Moraitis would sit in the garden. One day he planted a few vegetables. He started puttering around tidying the vineyard. Pretty soon he was building an addition on the house. “Today,” wrote Buettner, “35 years later, he is 100 years old and cancer-free. He never went through chemotherapy, took drugs, or sought therapy of any sort. All he did was move to Ikaria.” Buettner asked Moraitis if he had any idea how he’d recovered from lung cancer. “It just went away,” he said. “I actually went back to America about ten years after moving here to see if the doctors could explain it to me.” Buettner asked what happened. “My doctors were all dead.” Stories like these are inspiring headlines asking, Should I Retire in a Blue Zone? The short answer is probably not. There are five identified Blue Zones: Sardinia, Italy; Nicoya, Costa Rica; Ikaria, Greece; Okinawa, Japan; and the Seventh Day Adventist community in Loma Linda, California. Although they all enjoy good weather, a laid-back lifestyle, and healthy eating, each has drawbacks. Ikaria, for instance, has no major airport or hospital and is a long ferry ride from anywhere. What the Blue Zone folks have discovered isn’t a fountain of youth, it’s a lifestyle that removes major stressors that make us age faster: time-pressure, isolation, unhealthy food, and the self-fulfilling expectation that at 65 we’ll begin to deteriorate in a variety of embarrassing and debilitating ways. People in the Blue Zones don’t share those habits and attitudes, and maybe it’s time we got rid of them, too. You don’t have to move abroad to do it, although there are places — like Seville — that do make it easier. Personally, I am doing my best to adopt these eight elements of the Blue Zone approach. 1. An active social life. In the US, we tend to live further apart, and everyone’s so busy even dinner with close friends requires planning weeks in advance. On Ikaria, people tend to stroll out most evenings after dinner and drop in on their neighbors for a casual chat. Likewise, in Seville impromptu gatherings are common. New expats join social clubs such as the American Women’s Club and InterNations to find kindred spirits. This is vital, says psych professor William Chopik, because “as we get older, our friends begin to have a bigger impact on our health and well-being, even more so than family.” 2. The Mediterranean Diet. All Blue Zoners follow some version of it, bucking the American fast food trend spreading across the globe. Here in Spain, it’s much easier to eat a natural, plant-based diet. I follow Michael Pollan’s shorthand definition of this approach: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” 3. A little wine every day. A few glasses of wine in the evening is standard on Ikaria. I generally have just one, but I am considering upping my game. Strictly for health purposes, of course. 4. No gym, just natural exercise. I remember years ago dragging myself to brutal fitness classes. Never again. In Blue Zones, daily life includes a lot of walking and other gentle exercise, such as gardening. A large Swedish studied showed gardening and similar forms of puttering around can increase longevity by 30%. Put the money you save on gym fees into tomato seedlings. 5. Daily siestas. People in the Blue Zones tend to rest after lunch. They don’t always sleep; sometimes they read, meditate, or do something equally relaxing. But they hit the pause button and feel better for it. “Don’t think you will be doing less work because you sleep during the day,” said Winston Churchill, who lived to 90. “That’s a foolish notion held by people who have no imaginations. You will be able to accomplish more. You get two days in one — well, at least one and a half.” 6. Sense of purpose. "Everybody needs a passion. That's what keeps life interesting,” said Betty White, who lived and worked to the age of 99. You'll never lack for things to do during a move abroad, but eventually you will settle in and then it's time to develop other interests. Travel is top on my list, with writing and painting in the offseason. Rich has taken online classes on happiness, grumpiness, memory, justice, and astronomy. He arrives at every meal with lots to talk about. 7. No retirement from life. I start worrying whenever I hear recently retired friends say, “I never do anything. I have six Saturdays and a Sunday every week.” Leaving a job can be liberating; becoming a couch potato is less so. George Burns, who lived to 100, agreed. “Retirement at 65 is ridiculous. When I was 65, I still had pimples.” 8. Positive attitude. Blue Zone people don’t fret about aging because they don’t view old age as God’s waiting room but rather as having more time to do things. “Get busy living or get busy dying,” says Morgan Freeman, actor, producer, and political activist. He got his pilot’s license at 65, and at 85 is still having fun doing guest roles on shows like The Kominsky Method. So to recap: No, you probably don’t want to live in one of the Blue Zones. Yes, their lifestyle makes sense, and it’s not a bad idea to see if you can adopt some elements of it wherever you may be. If you're dreaming of living abroad, see how many of these eight elements you’ll find in destinations you’re considering. Maybe someday you’ll be the 93-year-old life of the party on an island somewhere. It’s a tough job but somebody’s got to do it. I'd love to think Rich and I could learn to do this, but to be honest, I couldn't dance like this on my best day at any age. Dietmar & Nellia, you rock!

WELL, THAT WAS FUN. WANT MORE? If you would like to subscribe to my blog and get notices when I publish, just send me an email. I'll take it from there. [email protected] Yes, my so-called automatic signup form is still on the fritz. Thanks for understanding. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY

13 Comments

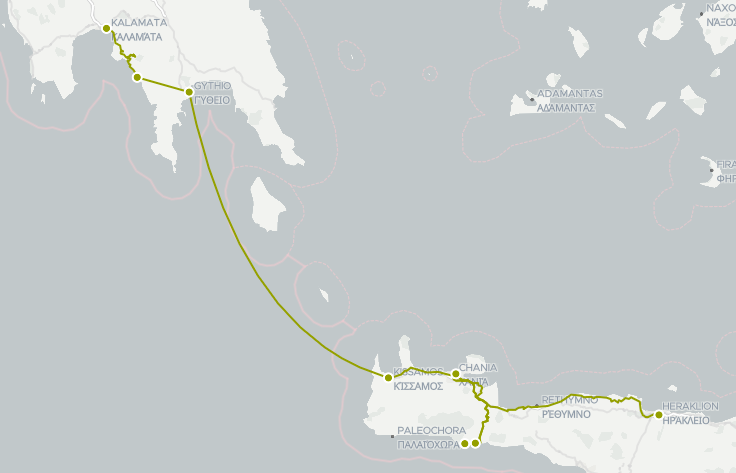

Rich and I thought we were prepared for anything — trains leaving at 3:30 AM, running once a week, or requiring awkwardly timed changes at obscure junctions. It never occurred to us that there might be no public transportation whatsoever between two major European cities just 146 miles apart. “Trains?” said the man at the Thessaloniki railway station, as if this were a foreign concept. He peered at my handwritten note. It read, “Thessaloniki —> Skopje Wednesday June 12.” He shook his head. “No. No trains to Skopje. After June 15, is possible. Now, no.” Rich shrugged. “Looks like we’ll be taking the bus.” Or maybe not. The lady at the nearby bus counter said, “Tomorrow. Next day. After that no.” “We want to go next week,” I said. “No. Tomorrow, next day, then is finished. No more buses.” “Ever?” I asked. She shrugged. “This is Greece.” Enough said. This left us in something of a quandary. Our goal is to complete the entire trip on public transit — trains, buses, ferries, the occasional taxi — never driving a car or taking a plane. What to do? We returned to the railway counter. “Could we buy tickets now for June 15?” I asked. It would mean three more days in Thessaloniki — not exactly a hardship. “No. I have no tickets. Maybe June 15, maybe not.” He paused then added, “They are Serbian trains.” As if that explained everything. Rich and I walked out of the railway station laughing and shaking our heads. There was a time we might have been a trifle perturbed at the idea that an apparently insurmountable obstacle was blocking our progress. But like everyone else in Thessaloniki, we were floating along on such a powerful caffeine high that nothing really bothered us. Coffee is the lifeblood of this city, and everyone, including us, is drinking plenty of it. Coffee houses abound, sometimes five or six on a block, doing brisk business at all hours of the day and night. Younger locals are sipping from go-cups on the street, in the shops, and at work. What’s in all those go-cups? Frappés and freddos, relative newcomers on the scene. For centuries, folks around here drank nothing but traditional Greek καφές, a thick Turkish-style boiled brew that somehow manages to taste like American instant coffee. And while you can order it sketos (without sugar), it’s so bitter nearly everyone takes it metrios (one heaping teaspoon of sugar), glykos (sweet, two teaspoons), or variglykos (very sweet, four teaspoons, at which point it’s more or less Red Bull). Then a single impulsive moment at 1957 trade fair changed the nation’s coffee culture forever. The Swiss manufacturer Nestlé was in town promoting instant Nescafé and a short-lived product involving chocolate milk made in a shaker. One day Nescafé employee Dimitrios Vakondios felt the need for caffeine but couldn’t find any hot water. On impulse, he borrowed the shaker from the chocolate milk rep and mixed Nescafé instant coffee with cold water and ice. The idea of iced coffee — shockingly radical yet undeniably attractive in this hot climate — caused an overnight sensation in Thessaloniki and soon became the drink of choice for hipper Greeks everywhere. The new drink was dubbed the frappé (from the French "frapper," meaning to hit, referring to the ice crashing around in the shaker). It can be served with varying amounts of white or brown sugar, with or without condensed milk, and — if you really want to feel the love — a scoop of ice cream. Frappés are so popular here that even Starbucks has added it to their menu. The frappé reigned supreme until the 1990s, when it was overtaken by the freddo, a similar iced drink made from the classier Italian espresso. It can of course be configured to any degree of sweetness, and if you want milk, you ask for a freddo cappuccino. Which is better? Rich and I decided to consult Natasa, the owner of Thessaloniki’s historic and arguably hippest café-bar: Thermaikos. Here’s what we learned from Natasa and her barista, Athanasia. Both drinks are fun, and if you get them fully loaded, they’re more like milkshakes than coffee drinks — which is no doubt why they’re so popular with the young. But if you hope to live to a ripe old age, you might want to stick with traditional Greek coffee. “Researchers studying heart health say that a cup of Greek coffee each day may be the key to the longevity of people on the Greek island of Ikaria, who live to age 90 and older," reported Dr. Gerasimos Siasos of the University of Athens Medical School. Greek coffee can determine your future in another way as well: the grounds are used by local psychics to predict the future. Which is why, when Rich and I were stymied in our efforts to leave town, I found myself at the café Ωκεανος (Ocean) for a reading with their resident clairvoyant. Elena is much in demand, and I had to take a number and sip my Greek coffee for over an hour while she did other readings. Shortly before my turn, she came and swirled the coffee around in the cup, tossed the liquid into a bucket, and upended my cup in its saucer to drain. Ten minutes later she was back, set the cup upright, and peered into my future. First, she saw a female relative who was giving me trouble. “A dark-haired women, a bit heavy.” Four generations of my relatives passed before my mind’s eye; no one matched the description. The reading stumbled along with the theme of business papers recurring constantly and the hope that some money might be coming to me. Somehow we never got around to the subject of travel arrangements. “What’ll we try next?” I asked Rich. “Travel agencies. Somebody must go to Skopje.” The first travel agency confirmed that no public or tourist buses were running to Skopje in the foreseeable future. As we emerged onto the street, a toothless old woman in black tried to shove a picture of the Virgin Mary into my arms. At my repeated refusals to buy it, she hurled a curse at me and stomped away. She and I had been through this routine three days earlier, just before our transit problems began. Hmmm, could there be a connection? “Do you think I need to buy some of her art to get our karma back on track?” I asked Rich. “Let’s hope not.” Eventually we learned that bus service has been extended a few days while negotiations continue. So we may or may not leave town next week, I might have an unknown, dark-haired, heavyset female relative plotting against me, and it’s possible I’ll have to buy some cheap religious art to lift a curse. In other words, we don’t have a clue about what the future holds. But then, does anyone? In the meantime, I’ll just relax over another cup of καφές. My Mediterranean Comfort Food Tour In 2019 Rich and I set off on an open-ended, unstructured journey to sample some of the world's best comfort foods — I know, a tough job, but somebody has to do it! Each meal gave me fresh insight into the character of the local culture. Right now I'm working on a book about my adventures; stay tuned for updates. My Other Eastern European Adventures My Move to Seville “Ya gotta give the guy credit,” I said around midnight, as Rich’s new friend led yet another 20-something woman onto the dance floor. “He’s got a lot of energy for eighty-four.” One of the locals laughed. “Eighty-four? He’s ninety-three.” I regarded the dancer with even greater respect. Not only was he the life of the panygyri, one of the traditional all-night parties with which Ikaria celebrates saints’ name days, but he was a living example of the locals’ legendary longevity. Designated as one of the handful of Blue Zones in the world, the island is full of people living remarkably long, healthy lives. I’d read articles on the subject aloud to Rich, adding, “We have to go there. Maybe it will rub off on us.” We arrived on the Sunday afternoon ferry and asked Dimitri, our hotel’s ever-helpful desk clerk, where to go for a late lunch. “Popi’s,” he said promptly. “The best food on the island, possibly all of Greece. Ten minutes’ walk up the coast road.” Twenty minutes later, as we staggered up yet another rise, we began to wonder if somehow we’d missed the place. Pulling out his phone, Rich discovered that Google had actually heard of Popi’s and informed us that it was just around the next bend, adding helpfully, “Closed. Opens again 1:00 AM.” “That can’t be right,” he said. We’d been told Ikarians refused to live by the clock, lightheartedly referring to any time of day as “late-thirty.” One young man I’d read about set off to buy coffee for his mother and didn’t return for three months. He’d run into friends en route to a panygyri, partied all night, gone to Athens, and gotten a temporary job. Presumably at some point he called home to suggest someone else should fetch Mom’s coffee. Obviously things were a bit looser around here. Still, opening at 1:00 AM? We soldiered on. Popi’s was just around the next bend, open, and serving some of the best food we’ve ever eaten. As we settled in the shade of the overhead vines, looking out over the tranquil Aegean Sea, we chatted with Zisis, whose mother had operated the place as a bar until he was born in 1993, at which point she converted it into a restaurant. I asked if he’d lived here all his life. “I went to work in Crete for a time,” Zisis told us. “Too much stress. It’s better here.” A relaxed lifestyle is one of the reasons ten times more Ikarians than Americans reach their eighties and nineties — and why their old age is rarely plagued with cancer, depression, or dementia. Another major factor is a diet based on the island’s wild greens, nutrient-rich herbs, seasonal vegetables, smaller amounts of food in general, and protein that’s mostly homemade cheese, fish, and goat. Goat is a surprisingly healthy option, far leaner than lamb or beef, with 40% less saturated fat than skinless chicken. And wild goat, it turns out, was the specialty of the house at Popi’s. Now I know what some of you are thinking: How could I consider eating one of those cute little goats that had bleated a greeting as we passed, peering curiously at us from the hillside next to the restaurant? Well, right now, Ikaria is hideously overrun with goats, thanks to EU subsidies rewarding larger herds. On an island with just 8423 residents, there are currently 35,000 goats, most roaming free and wreaking havoc on the ecosystem. Islanders are desperate to cull the herds to keep their island’s vegetation healthy. I decided to do my bit to help. “Want to try some wild goat?” I asked Rich. “Will you show me how you make it?” I asked Zisis. To my delight, they both said yes. Zisis explained the meat was super fresh, having been butchered that very morning. They raise their own goats and get more from relatives and friends. “Some goats are kept in pens, but many are free. And then the people must go hunting.” Asked to pin down quantities for the recipe, Zisis estimated he starts with about 2.25 kilos of meat. Because it’s so lean, formal cuts such as loin and shoulder aren’t practical; instead you make “village cuts,” dividing the meat any way you can, so long as it winds up a size that’s roughly suitable for cooking. You add lots of salt, pepper, and about three quarters of a cup of olive oil. You cook the meat in a ceramic pot at 200 degrees Celsius (400 degrees Fahrenheit) for an hour and a half to two hours. The cooking brings out the meat’s natural juices, but check it a few times and if it seems dry, add a little vegetable broth. When the meat is tender and the smaller bones practically liquified, you take it out of the oven and sprinkle it with fresh herbs. Often this includes oregano, which is full of vitamins, antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, digestive aids, and much more. A study showed the variety grown on the island is three times more nutrient-rich and aromatic than the kinds in other parts of Greece. (I hate to even think how our American corporate version might compare.) But the most important thing we learned is that wild goat cooked in its own juices and garnished with wild herbs tastes simply marvelous — succulent, rich, and comforting. Learning how to cook goat was just one small part of our effort to live as “Ikarianly” as possible while we’re here. We’ve eaten local foods, sampled the local wines, and danced at the panygyri. Letting go of our sense of time, we’ve been easing around town at our best approximation of the locals’ relaxed pace, stopping often to linger in cafés and on our favorite wharf-side bench. Don’t get me wrong; this isn’t an island of slackers. People get plenty done. They just do it their own way. Errands, for instance, often involve leaving their car in the middle of the street, their motorcycle at the curb with the keys in it, or their bicycle propped unsecured against a lamppost. Ikarians don’t sweat the small stuff … or the large stuff either. My goal in life is to find more ways to be like them. And of course, to eat more wild goat. “This isn’t coffee,” Rich said, glaring into his cup. “It’s gasoline.” “No, there’s definitely some coffee in it because I have grounds stuck in my teeth.” We set down the cups of revolting brew and stared around us at Kalamata, Greece: gloomy sky, empty street, silent men hunched over scattered tables under two giant trees. I could almost hear the blood from Rich’s leg wound dripping onto the paving stones underfoot. It was a low point in a day that had started with a setback and gone downhill from there. We’d awakened that morning 50 kilometers to the south in Agios Dimitrios to discover the village was in the grip of a power outage and a sirocco. Fierce, sand-laden winds that blow up from the Sahara, siroccos turn the Mediterranean sky a gritty gray and (they say) drive people mad. During the Ottoman era, if you murdered someone during a sirocco, you got a lesser sentence due to extenuating circumstances. Rich and I managed not to go berserk, even when we realized without electricity we couldn’t make coffee. The landlord of our rental apartment gave us a lift to the bus stop, conveniently located in front of the café run by Freda, widely known as the village’s most resourceful resident. She didn’t fail us now. Working with a car battery and a gas-powered burner, she produced French-press coffee for us and our friends, Jackie and Joel. Many of you know Jackie from TravelnWrite, her lively blog about expat life in Greece. After corresponding for years, we finally met IRL (in real life), and not only had she and Joel generously spent days showing us around, they came to see us off on the bus — a bright spot in the morning. “Does the sirocco always knock out the electricity?” Rich asked. “Oh no, this is a planned outage,” said Jackie. “They must be fixing something.” The outage and the sirocco extended all the way up the coast to our next stopping point, the city of Kalamata. After the picturesque charms of Crete and the rugged magnificence of the Mani Peninsula, our first glimpses — and frankly, our second and third glimpses as well — suggested that Kalamata was a soulless wasteland of shabby, crumbling concrete. We were too early to check in, so our Airbnb hosts kindly directed us to their favorite café, just around the corner under a pair of huge trees. Stepping into the deeper gloom below the branches, Rich immediately walked into a low metal table, gashing his shin. As he hobbled to a chair and began sopping up the blood with his handkerchief, I ordered coffee — the only item on offer. They were likely heating the water with kerosene, which could account for the taste. “I gotta tell you,” said Rich. “I am not warming to this town.” Disinclined to linger at the café, Rich tied his handkerchief around the wound and we set off to reconnoiter. Hours of walking took us past closed shops, lightless windows, and a few shadowy restaurants serving coffee. Suddenly Rich’s sniffer went on high alert. “Do I smell food cooking?” he said. We followed our noses into the steamy warmth of a café, where a gas cooker had produced an array of hearty dishes. In a matter of moments we were seated before heaping portions of moussaka, green beans, and chicken "mincemeat." We sighed with pleasure and tucked in. Ten minutes later the lights came on and the sun came out. Leaving the restaurant, we found ourselves surrounded by bright, inviting shops and cafés with abundant charm and originality. Our apartment turned out to be even pleasanter than it looked in the photos. Rich grudgingly agreed the town might have some redeeming features. The next morning we took a food tour, and our guide, Fotini, introduced us to local characters as well as local cuisine. Tourists are relatively rare creatures in Kalamata, and everyone seemed delighted to spend time with us. The Economakos family gave us slivers of their famous salted pork and cups of homemade wine as they showed us a picture of the sausage plate that won first prize the 1999 trade fair. We nibbled and sipped our way through the morning, shaking hands, kissing cheeks, promising to come back one day. Kalmata’s world-famous olives were mentioned only in passing, and I asked Fotini why there wasn’t more fuss about them. She shrugged. “When you’ve been eating something since ancient times, it is just a part of everyday life.” I asked if there were any special dishes we should try while we were in town. “Gourounopoula,” she said. “Roast pork with plenty of skin and fat. Back in the days of the Ottoman empire, we used it to plan a revolution. When we had feasts, we of course had to invite our Ottoman neighbors. But being Muslims, they didn’t eat pork, so when we served gourounopoula, they stayed away. And we could plan our revolution, right under their noses.” Thanks to gourounopoula — and a few other factors, of course — the Greeks gained independence in 1829 after 400 years of Ottoman occupation. Where we should try this famous pork? Fotini led me to the corner and pointed. “There. That café with the two giant trees.” “No way,” said Rich. “Oh, man up,” I said. “Let’s see if that little table is ready for a rematch.” “I want a second opinion.” When we asked at the tourist office, the woman at the desk sighed ecstatically.“Ah, gourounopoula,” she said. “Yes, you must try it. The best is here.” She pointed at the map. “At Barbayiannis.” We set off, hampered only by the fact most streets weren't marked, and the few that were didn't seem to match any of the names on our map. Eventually I noticed a window displaying the remains of a pig, with a severed head and a meat cleaver. We had found Barbayiannis! I did a doubletake. "Hey, this is the place we had lunch the first day!" What are the odds? Gourounopoula was comfort food at its finest: a crispy outer layer of roasted fat covering meat tender enough to cut with a fork. I didn’t even try to talk my way into the tiny kitchen during the lunchtime rush, but I did the next best thing and looked online for a recipe. Ideally you roast the pig whole on a spit, but when that's impractical, this video shows how to create the same effect with a pork shoulder roast and a few other simple ingredients in your home oven. “I can’t believe I’m saying this,” Rich told me. “But I actually think Kalamata is my favorite stop so far.” “You’re just saying that because you’ve stopped bleeding and have a belly full of roast pork.” “I rest my case.” LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR MEDITERRANEAN COMFORT FOOD TOUR.

SIGN UP TO RECEIVE UPDATES AS WE GO. AND SEND US YOUR COMMENTS BELOW! YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|