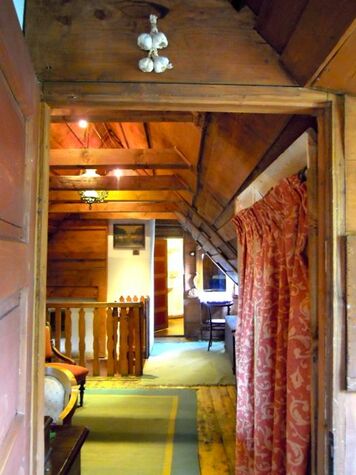

Woman in the Augustin train station Woman in the Augustin train station Sitting around a Transylvania dinner table, one of the British guests told me he’d recently met some Texans in London who, upon learning he was heading to Romania, said apprehensively, “But is it safe?” Romania is a wild place, but having spent some weeks here, it seems to me you’d have to go out of your way to incite actual trouble. Oh sure, we had momentary doubts when we arrived at the train taking us to rural Augustin and discovered it was packed to bursting with large, sinister-looking fellows in rough country clothing. Men in fedoras and cloth caps were shouting over a card game, cigarettes dangling from their lips. The pungent tobacco smoke provided a welcome counterpoint to the eye-watering scent of unwashed bodies. Babies wailed in their mothers’ arms, and somebody was playing tinny folk music on what sounded like a transistor radio but was probably a cheap phone. “This is fabulous,” I said to Rich as the train jolted over the tracks. “It’s the closest I’m likely to get to riding in a gypsy wagon.” When the conductor came around for tickets and everyone learned where we were headed, several people – including Rich’s seatmate, who looked like a hired assassin and was reading a Bible – volunteered to make sure we got off at the right station. By the time Rich passed around some mints, we were all fast friends – or at least the kind of acquaintances that you no longer worry will rob or kill you.  Garlic over the door of our room in Miklósvár Garlic over the door of our room in Miklósvár Feeling safe with strangers is a relatively new thing in Transylvania. Over the last 2000 years, this lovely part of the world has been dominated by Romans, Carpi, Visigoths, Huns, Gepids, Avars, Slavs, Bulgarians, Magyars, Hungarians, the Ottoman Empire, the Hapsburgs, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Nazis, the Communists, and now global modernization, to name but some of the highlights. Getting a grip on Transylvanian history is like trying to unravel the plot of the tv series Lost. Suffice to say that anything that will ward off evil, such as putting a red thread in your livestock’s hair or nailing garlic over the doorway, is still seen as a pretty good idea. In the old days, churches were heavily fortified, and during services Saxon congregations required the men to sit along the outer walls of the room, forming a protective circle around the women and children. “The young girls sat in the back,” our guide explained. “As they aged, women moved up closer and closer to the altar; the oldest ones sat in these front pews, with the black angels painted on the walls.” Even today, the oldest women in these villages are referred to as “sitting with the black angels.”  Father and daughter straining sheep's milk Father and daughter straining sheep's milk Today’s young women aren’t sitting in the back pews, they’re out getting educations and jobs. Even such long-standing male bastions as shepherding have changed with the times. We met a teenage girl apprenticing with her father, who with another shepherd lives much of the year on a hillside with the flock, milking 400 sheep three times a day. The raw milk is processed into cheese in a nearby hut, under hygiene conditions that frankly made me blanch. When we were offered samples of extremely fresh cheese, it was all I could do not to ask, “But is it safe?” Evidently it was, because I am still among the living. Things change slowly in rural Transylvania. We were staying in the village of Miklósvár (established in 1211, population 512, not counting us) and our favorite moment of the day was watching the cows come home. The local cowherd collects each family’s cow at sunrise and takes them all into the hills to graze. At sunset, they all amble slowly up the village’s main street, each cow turning into her home gate where the family waits to greet her.  Romanian farmers tie red string on their animals to ward off the evil eye. Romanian farmers tie red string on their animals to ward off the evil eye. Two goats bring up the rear of the procession, sometimes pausing to snack in various gardens along the way. One evening, one was standing right in the middle of the road when a truck came zooming up behind it. “Looks like we’ll be having goat for dinner,” Rich remarked. But the goat had other ideas. He didn’t even deign to glance around, just planted all four hooves and stood there. The truck honked, braked, honked again, and finally slewed wildly to the left. At the last possible second, the goat moved off to the right, giving a little kick of his heels as if to say, “Take that, modern world.” I love this attitude, and it breaks my heart to know that the traditional Transylvanian culture is not safe; it’s sitting with the black angels, destined to disappear from the face of the earth very soon. But for now, I take comfort in knowing that every day at sunset, as I close my computer and head out for a beer with friends, the cows of Miklósvár are ambling along the street, finding their way home, where their families are waiting for them.

12 Comments

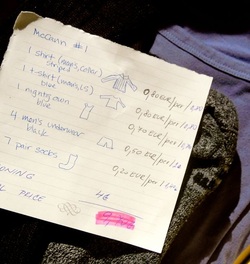

So we get off the train at the station – more of a shed, really – in the dark, in a small village deep in the Carpathian Mountains of Romania, and despite email promises, no one is there to meet us. The unpaved road holds no taxis, cars, or even the horse-drawn carts we’ve been seeing in villages along the way. Part of the reason I love train travel is that it makes me feel like I’m living in the 19th century. An era, I now recall, that has some pretty dark chapters, including a few set in this very region. “Are those bats?” Rich asks, as something flutters by at the edge of my vision.  A smiling man appears suddenly out of the gloom. “I take you!” “Did George send you?” I ask. The man seizes our bags. “I take you!” And off we go in his car. There are moments when you simply have to trust your instincts, your luck, and whatever saint watches over travelers now that St. Christopher’s been debunked. Some 30 km later, we arrive at his snug wood and cement house, where his wife and a hot meal await us. And in the morning, we look out our window to discover that we have gone back 700 years and are in the midst of the medieval village of Botiza. Despite evidence of various modern conveniences – electricity, indoor plumbing, a cell phone tower – most of the villagers still live in much the way their ancestors did back when Vlad the Impaler was a boy. We are charmed and dazzled by the opportunity to hang about the village, exchanging polite greetings with the locals, who seem utterly unfazed by the presence of a couple of foreigners – who might as well be time travelers, given the differences in our lives. This is no Disney version of ye goode olde days, but a place where things change very, very, very slowly. Most families build houses and barns by hand from wooden planks cut from trees in the nearby forest. They raise chickens and may own a cow for milk and/or a horse for transportation and labor. In September, they scythe the hay, haul it back in a horse-drawn cart, dry it on racks made from saplings, then pile it into haystacks handy to the barn. They work long and hard every day and go to church on Sunday. When I asked what they did for fun, I was told that some Saturday nights there are weddings, with music and dancing, and the whole village attends. Other than that, once in a great while someone might stop by for a beer. This is the central bulletin board that lists all present and upcoming activities in the village. Not surprisingly, most of the teens are counting the days until they can head to the nearest city, dye their hair, get tattoos and piercings, join a rock band, find a desk job, and forget they ever came from this nowheresville. As for their elders, some have part-time jobs in town, but mostly they’re hanging on to the old ways. Looking to the future, many have already bought their coffins, tombstones, and burial plots in the village cemetery. But modernity is creeping in. Their ancestors would never have used an exclamation point on a gravestone, but thanks to Facebook and other social media, punctuation standards have changed!  “Stop! Our passports! Stop the train!” we shouted out the window. The Hungarian-Romanian border is no place to lose your passport, and it had been with some reluctance that we’d turned ours over to a couple of burly men in uniform who'd come on board, headed directly for our compartment, taken our passports (and no one else's), disembarked, and disappeared into the station. We weren’t even sure which country we were in. Had their badges said bevándorlási tiszt or ofițerul de imigrare? I didn’t have a clue. Meanwhile, the station attendant whiled away a quarter of an hour checking the brakes, slamming doors, and finally waving his paddle to indicate the train was ready to move on. Rich and I heard the engine start and felt a jolt, and that’s when we leaned out the window shrieking, “Our passports! Stop the train! Passports!” Only then did we realize that our part of the train wasn’t, in fact, going anywhere. The OK-to-go signal was for the back half of the train, which was separating from our section and returning to Hungary. The fact that everyone on the station platform knew this, and had doubtless seen this little drama enacted countless times, didn’t seem to diminish their innocent delight in watching us make fools of ourselves. Luckily, we’ve taken so many linguistic and cultural pratfalls by now that we didn’t hesitate to join in the general merriment.  Rich and I have been jumping on and off trains since August 4; so far, we’ve logged 2416 rail miles (3688 km), and we still feel a little thrill every time we step into a railway station. It’s a civilized form of travel from a more civilized age. There are no security lines, no x-ray machines, no one demanding that you take off your shoes or stand spread eagled like a criminal while strangers run wands – or their hands – all over your body. With a pre-paid pass, you simply stroll into the station and onto your train. If you’re thinking about strolling onto European trains any time soon, here are a few tips you might find useful. A flat-rate train pass is great if you’re traveling more than a month and planning to visit lots of different cities and/or countries. There’s InterRail for EU residents, EurRail for everyone else. Each offers roughly similar benefits and costs, although there are various plans, and you’ll want to study the fine print. EurRail, for instance, covers much of Europe except, inexplicably, Poland, Slovenia, and Montenegro. InterRail doesn’t include travel in your home country. A few portions of the journey may require reservations, and there can be extra fees for high-speed and overnight trains. For some reason, the EurRail pass is printed on flimsy paper so a plastic case is a must.  Hungarian train station rest room attendant's table Hungarian train station rest room attendant's table Punctuality will vary where you least expect it; Austria’s trains proved less reliable than (gasp!) Spain’s. And even the highly efficient iRail app can’t keep up with all the sudden schedule revisions; we’ve occasionally had to re-route completely due to sudden, mysterious disappearances of scheduled trains, and it’s not uncommon that the five stops listed can become ten or twenty, contributing to a late arrival. So we check and re-check schedules on the Internet, drop by the train station the day before to confirm, then arrive early and check again. And while we have, astonishingly, made several five-minute connections, we always check to see if there’s a later train, in case we don’t. I’ve posted on this before, but it bears repeating: never chase a missed train; get a pastry and wait for the next one. In fact, we spend a lot of time in station cafés, not so much because of missed or changed trains, but because we follow the wisdom of Wandering Earl, who always stops for coffee on arrival in a station. Taking a few minutes to have coffee (or juice, Coke, beer, or even a meal) lets you regroup, confirm the route to the hotel, and absorb the atmosphere of this new place before you go charging out into it. Right now, Rich and I are absorbing the atmosphere in the charming Rumanian city of Oradea, one of Europe's hidden gems. Tomorrow we’ll be heading deep into the Transylvanian mountains, on smaller and smaller trains, with less and less certainty that there will be electricity, let alone WiFi, for the next couple of weeks. We’ll be back in touch when we can, with stories about taking a slow train through Transylvania...  My beer with grapefruit flavoring & straw My beer with grapefruit flavoring & straw “And after dinner, of course,” said one of our new friends, “vodka and pickles.” At this point in the evening, I felt nothing could shock me. Earlier I’d been staggered to observe people in many of Krakow’s charming bars casually drinking liters of beer through large plastic straws. When I asked a local woman about it, she laughed and said, “Oh, that’s not beer.” I was so relieved; call me old fashioned, but somehow sipping beer through a straw seems to be flying in the face of nature. “No,” she continued. “That’s beer with ginger flavor added to it.” I was still reeling from that appalling revelation when a round of tiny vodka glasses appeared on the table along with huge green pickles. “You eat them after drinking the vodka,” someone explained. “It helps keep you hydrated.” Oh, well, if it’s good for my heath… Na zdrowie! After a month on the road, I’m still gobsmacked by how much I have to learn about the world. So far we’ve traveled through Spain (Seville, Barcelona), Italy (Genoa, Verona), Germany (Munich), Austria (Salzburg) the Czech Republic (České Budějovice, Český Krumlov, Prague) Poland (Krakow, Katowice), and Slovakia (Zilina, Košice). We’re now proceeding towards Transylvania by slow stages, hopping from one hitherto unknown spot to another. As we stumble on and off trains, we find we’re confronting many of the essential travel questions people have been asking since our earliest ancestors first wandered over into the next valley and discovered another tribe.  How do you communicate without a common language? Zipping in and out of so many countries, we scarcely have time to learn how to order beer in our new temporary language, let alone master the nuances of conversation. But if you’ve ever played charades or Pictionary, you’ll know that words aren’t everything. Last week I stopped into a hair salon in Krakow, pointed at my gray roots and made scissor motions at the tips of my hair; my new fryzjer knew just what to do. Similarly, when I arrived in Košice yesterday and wanted the hotel to wash our things, I simply made drawings of the various items, which not only amused the desk clerk no end, but insured that we received every item back this morning.  New friends met via AirBnB New friends met via AirBnB Can you turn strangers into friends, or at least acquaintances? Finding congenial souls along the way enlivens the journey and gives you fresh topics to think and talk about afterwards. One of the best ways to meet interesting people is to take a free tour. You usually get the liveliest and most knowledgeable guides, who are highly motivated by your tips and the hope of luring you into taking more tours; people who take free tours tend to be slightly less conventional and more open. Another way to connect is by renting a room or apartment directly from an expat or local via AirBnB, where you’re likely to find cheaper, homier places and a host who knows the best bars in the neighborhood.  Our hotel in Katowice, Poland Our hotel in Katowice, Poland What makes for the most memorable experiences? We recently had a one-night stopover into Katowice, Poland, a gritty, post-industrial town whose mines were exploited by the Nazis and the Soviets, leaving a landscape dotted with the monstrous, rusting hulks of derelict factories. “Katowice is the butt of jokes throughout Poland,” a tourist brochure informed us, rather unnecessarily. At the train station’s information booth, we asked the two young men on duty how to get to our hotel, which was 300 meters away. The tall, skinny one with the braces started to answer, the short, stocky one disagreed, and they went back and forth like two wild and crazy guys from the old Saturday Night Live routines until Rich and I went into whoops and had to hurry away. We soon found our hotel, which was so close to the station that we could here them announcing trains from our room. My point – and I do have one – is that getting off the beaten path lets you experience all sorts of odd and entertaining encounters. Our night in Katowice was like stepping back in time to the old Soviet days, only with better food and the opportunity to leave in the morning. There isn’t nearly enough space in a single post to fill you in on all we’ve learned, so watch for future updates on lodging, packing, train travel, and of course, drinking customs around the world. Na zdrowie! |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|