|

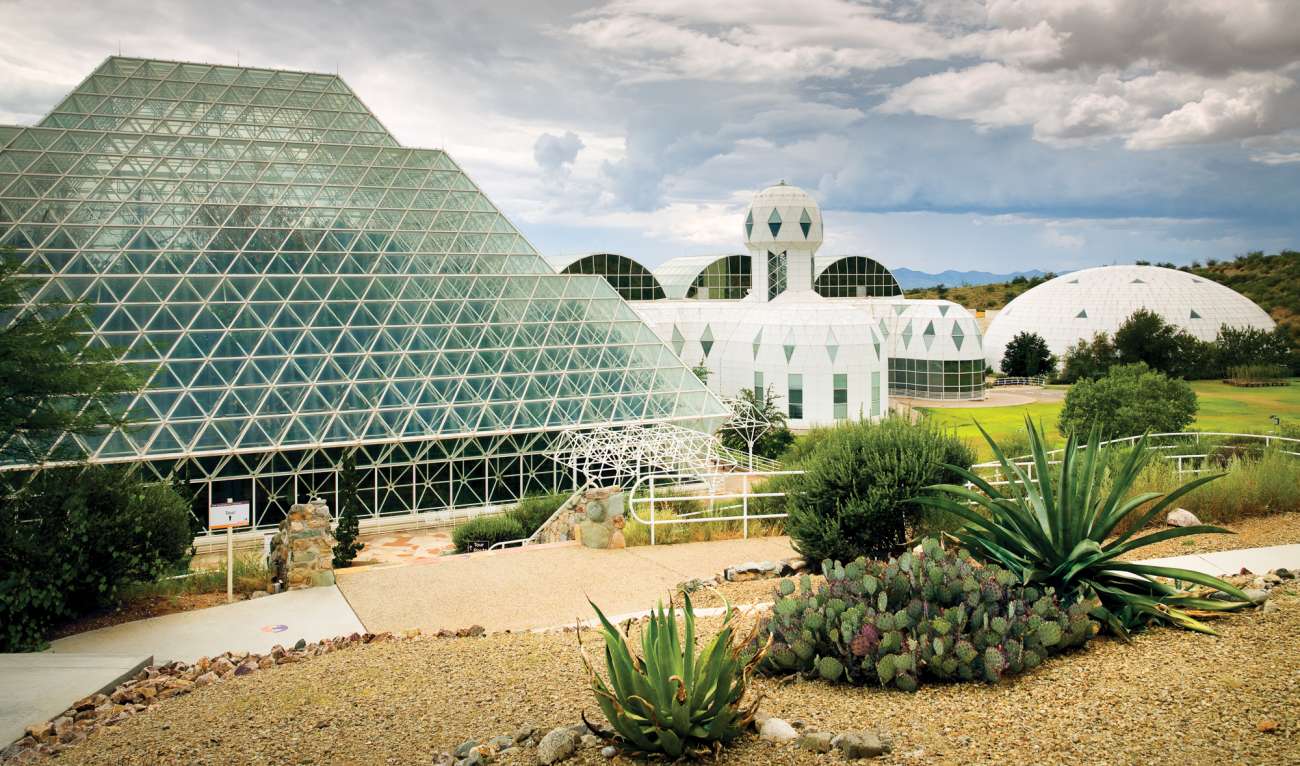

You never really appreciate the little things — food, air, freedom from octopus invasions — until you lose them. Not that I’ve ever lost those things, gracias a Dios, but last week I had the rare opportunity to visit a place where back in 1991 eight people – visionaries? Lunatics? Cult members? — suffered all that and more. Why? Because they voluntarily sealed themselves inside a giant glass-and-steel structure for two years in an outlandish experiment known as Biosphere 2. (What’s Biosphere 1? That would be the planet Earth.) You may remember the early rapturous announcements about the project: this human laboratory in Oracle, Arizona was going to teach us to save our own planet, show us how we could live on Mars, and provide new benchmarks for human endurance and scientific knowledge. The gorgeously designed 3.14-acre enclosure recreated various Earth habitats— savannah, ocean, rainforest, etc. — and the four men and four women living inside it would conduct studies and experiments that were impossible to carry out in Biosphere 1. Discover magazine called it "the most exciting scientific project to be undertaken in the U.S. since President John F. Kennedy launched us toward the moon." Talk-show host Phil Donahue, broadcasting live from the site, called Biosphere 2 "one of the most ambitious man-made projects ever." What could possibly go wrong? Plenty, as it turned out. For start, Mother Nature had her own ideas. The morning glory vines grew so vigorously they blocked sunlight urgently needed by edible plants. UV light entering through special glass delighted the lizards but also attracted and killed the bees, so the humans had to pollinate the plants by hand. Baby octopi, accidentally carried in on the coral, began happily eating the oysters, crabs, and fish meant for human meals. Small monkey-like prosimian galagos, intended as companion animals, ran amok, raiding supplies and wrecking instruments and experiments. The little scamps soon disappeared from the official record, and I couldn’t bring myself to inquire more deeply into their fate. As it happens, Rich and I had visited Biosphere 2 during the late 1990s, after the experiment was shut down. Having read various “had-we-but-known” articles about the project, we were unsurprised to see nothing but a glass-and-steel dome overrun with plants. But at its peak, the project was a heady mix of science experiments, public vindication for the holistic vision of the swashbuckling leader, John Allen, and performance art. Hundreds, often thousands of spectators and members of the media gathered outside daily, peering into the glass dome, shouting questions and encouragement. Celebrity visitors included sci-fi author Arthur C. Clarke, Jay Leno, a Tibetan lama, a Mexican sorceress, Disney CEO Michael Eisner, the cast of Cheers, members of NASA, and leaders of the Smithsonian. Between farming, science, and media interviews, you’d think the eight biospherians wouldn’t have much spare time to get into trouble. But you would be wrong. Yes, romantic liaisons formed. Then things got tense as food supplies ran low, cockroaches overran the dome, and oxygen levels dropped dangerously. To make matters worse, the biospherians could only grow enough coffee for one cup every few weeks. The group split into two factions of four, with one side loyal to Allen’s holistic vision, the other staunchly defending scientific method. Outside the dome, conflict raged between Allen and Ed Bass, who’d put up $150 million and expected to have more influence over the project. (Go figure.) Heads began to roll, staff members ran for the hills, and the press started referring to Biosphere 2 as “New Age drivel masquerading as science." Incredibly, the eight biospherians soldiered on, accomplishing some solid research and sticking it out for the full two years. It was actually two years and twenty minutes, thanks to Jane Goodall’s long keynote speech. As the eight biospherians waited impatiently for the airlock doors to open, one recalls thinking, “Jane, let us apes out of the cage!” When they were finally released, they rushed outside into arms of their loved ones — only to recoil at the stench of the perfumes and chemicals they wore, which seemed strange and repellant after two years using nothing but natural, unscented soaps and shampoos. The saga continues with a second crew entering Biosphere 2 for a stay that would be abruptly cut short. Outside, senior management were in open warfare. Meanwhile, two bisospherians from the original crew came back in the middle of the night and opened all the doors to “free” the team inside — who had no interest in leaving. Then, just when you’d think the story couldn’t get any more bizarre, it seems Bass called upon — of all people — Steve Bannon, who arrived with a restraining order and armed guards to take over and sort things out. Eventually the project was shut down and much later the property was purchased by the University of Arizona for scientific research. Best of all (from my point of view, at least) it’s now open to the general public. I hadn’t heard about its renaissance as a roadside attraction until last week, when I was visiting friends in Tuscon and glimpsed a highway sign. “Hey, did that say Biosphere 2?” “Yes,” said my friend. “We were thinking of going there tomorrow. Taking the tour.” “You mean we don’t have to stand outside with our noses pressed against the glass this time? I’m in.” We spent hours climbing around the habitats, threading our way through the labyrinth of maintenance tunnels underneath, and imagining what it would have been like to be sealed inside for two years.  When the tour was over, I asked our guide to recommend a book about the project. “If you want to read about the fights and all that,” she said, “get Jane Poynter’s The Human Experiment: Two Years and Twenty Minutes in Biosphere 2. If you want to know about CO2 levels there are several scientific works…” I think you can guess which book I immediately downloaded onto my Kindle. “Later,” wrote Poynter, “people would ask me why I wanted to give up two years of my life to go inside Biosphere 2. I could never understand this question. I did not view it as giving up two years, but gaining them. I wanted to be part of something bigger than me. It was historic. It would make my career. It would be the closest thing to living on Mars. I would find out for myself whether man-made biospheres work. I would experience being enclosed for two years, isolated from the world, so I could impart my knowledge and experience to those who followed, hopefully on their way to Mars.” Biosphere 2 may not have achieved all its loftier goals, but as a roadside attraction it is second to none. The backstory is astonishing. The visuals are spectacular. And it all makes you appreciate just how delicately our planet’s ecosystem is balanced on the knife edge of survival. Would I ever have been tempted to become a biospherian? Oh, hell no. They lost me at “one cup of coffee every few weeks.” YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY

10 Comments

When friends offered to take me to a dive bar in San Francisco, I was a trifle worried it would turn out to be hopelessly trendy, serving $25 cocktails and gluten-free vegan cuisine garnished with three kinds of Himalayan pink salt. But last night I was delighted to discover that Glen Park Station was the real deal: friendly and unpretentious, with a sticky wood floor, quirky signage, and a juke box belting out Frank Sinatra tunes. Rumored to be a speakeasy in the 1920s, it still keeps things anonymous with dim lighting and a cash-only policy. The slightly seedy, mildly eccentric atmosphere was the perfect backdrop to our Asparagus Day celebration. Never heard of it? Me neither. But I’d recently stumbled across a strange factoid: on that very date in 1891, the first shipment of asparagus arrived in SF from Sacramento. Why was this important enough to be listed on a world history site? I have no idea. But in honor of the anniversary, I wore my new asparagus-green raincoat and brought fresh spears of asparagus for the five of us to use as swizzle sticks. We’re still working on the lyrics to our theme song, “Age of Asparagus.” Later we strolled down the street for pizza, prosecco, and tiramisu — because hey, Italian food is always a good idea. Afterwards, replete and content, I reflected on how much the world owes to the countless generations of Mediterranean cooks who have defined the very concept of comfort food. Would life be worth living without pasta, olive oil, or gelato? Possibly, but the world would certainly be a lesser place without them. Mediterranean food: it reminds us that it’s fun to be alive. The idea that food should be eaten for pleasure did not loom large in my family. Like many Americans of my generation, I was taught to regard cooking as a scientific enterprise, a carefully calculated sum of fat, protein, and calories ingested for fuel and conveniently delivered via foods raised, prepared, packaged, and sold by a corporation. Every bite was a trade-off. “No more casserole for me or I’ll have to do an extra half hour on the Stairmaster tomorrow!” If you play word association games with Americans, you’ll find that the most common response to “chocolate cake” is “guilt.” Not so the Europeans. The French say “celebration.” In Spain, when dessert arrives on the table, everyone leans forward murmuring, “Que rico!” How rich! And nobody turns down a slice. In much of Europe, there’s a common understanding that feeling guilty about food isn’t sensible; au contraire, food is welcomed as a friend. Older Sevillanos still remember the desperate shortages following the Civil War, when no one got enough fat, calories, or protein, and all too many were forced to eat pigeons or pets to survive. Today’s Sevillanos take enormous delight in sitting down to dine on such classics as solomillo al whiskey (pork loin in whiskey sauce, smothered in garlic) and rising from the table with a pleasantly full belly. Most of the foods we consider Mediterranean classics were born out of such shortages, created by poor families struggling to put meals on the table in a region with notoriously rocky, sandy soil and searing summer heat. Cooks worked with what they could raise: olives for oil, seeds, beans, cereals, fruits, and vegetables, with a little fish, some cheese and yogurt, and practically no meat. People on this diet tend to live longer, healthier lives, so naturally this has spawned an entire industry of Americans busily analyzing its success. Just last month the Mediterranean diet was declared 2019’s best overall diet by US News & World Report, scoring top marks in the categories of best diet for healthy eating, best plant-based diet, best diet for diabetes, and easiest diet to follow. But for the millions who live the lifestyle, it’s simple. Nutrition guru Michael Pollen summed it up neatly in just seven words: eat food, not too much, mostly plants. The key, he explains, is to eat fresh, authentic, unadulterated food, not products loaded with chemicals, additives, and excessive sugar — all of which can leave you unsatisfied, and craving more. When you must buy packaged food, read the label. If it contains ingredients you can’t pronounce, or if sugar’s among the first three ingredients, you’re better off choosing something else. Another key element is enjoying your food slowly and, when possible, in good company. We’ve all watched movie scenes in which three or four generations gather in a garden at a long table loaded with gorgeous food and bottles of wine, with kids and puppies playing underfoot. If you’re thinking that’s life the way it should be lived, you’d be right. Eating a leisurely, communal meal usually means you’re eating a more varied mix of better, fresher foods, and by taking your time, you digest them better, feel fuller on less, and enjoy yourself more. The bottom line is this: Mediterranean food is great for your heart, both medically and metaphorically. The good news is, you don’t have to travel to Europe to experience it. In fact, the best Mediterranean fare is made right in your own kitchen and shared with the people you love. To help you get started, here are a few recipes to play with. Bon appetit! Check out my food videos to learn how to prepare some of my favorite Mediterranean dishes. Want more? Here are fabulous recipes (most of which I haven’t tried yet but they’re on my list):

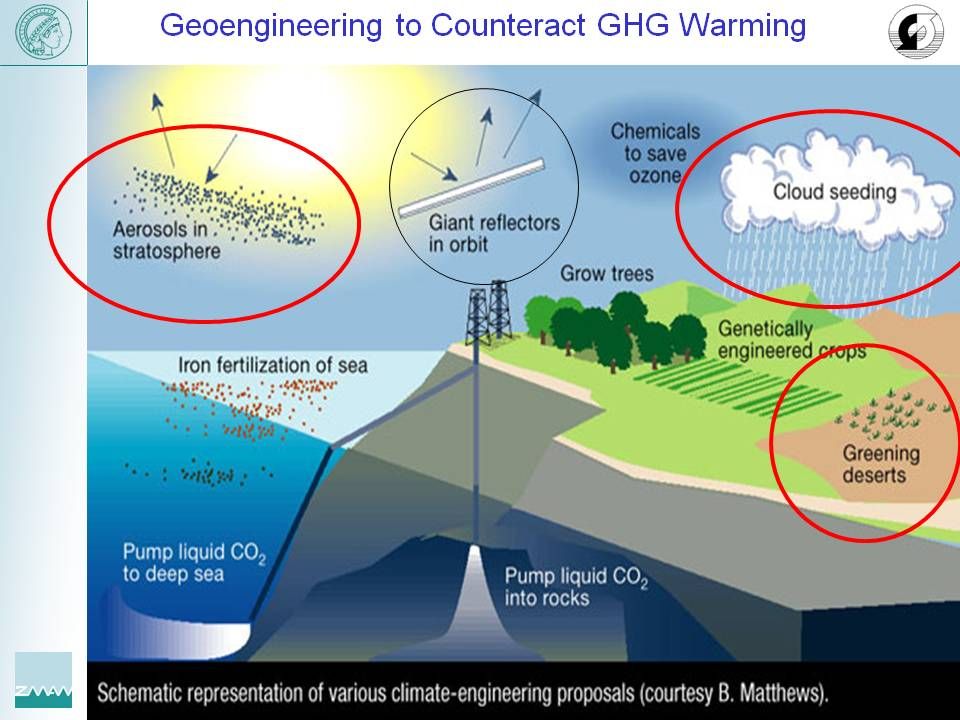

20 Best Mediterranean Recipes of 2018 My Greek Dish Spanish Sabores Great Italian Chefs 9 Classic Dishes from Provence “Does our township have an emergency plan?” I asked officials a few days after 9/11. I was living in semi-rural Ohio, just two hours from the Pennsylvania field where United Flight 93 crashed down. My neighbors and I were all keenly aware that plane had passed through our airspace and could, if events had unfolded on a slightly different timeline, have come down in one of our fields. Or on any one of us. “Of course we have an emergency plan,” I was told. When somebody finally managed to dig up the one-page document, it basically said, “Call the county.” When I spoke with county officials, I was told that in a major emergency we’d be on our own for at least 72 hours, and after that the plan was “Call FEMA.” What could possibly go wrong? New Orleans, 2005; victims of Hurricane Katrina beg FEMA for help. I stopped by our Ohio township’s volunteer fire department. “We’re just 20 miles from a nuclear power plant,” I said to the chief. “What happens if there’s a disaster there? I’ve read that we’re supposed to shelter in place, but how?” “Shelter in place? Are you kidding?” he replied. “If there’s a disaster at the nuclear power plant, everybody in this town will get in their car and drive to Florida.” And who could blame them? Today, that “hey, what can you do?” attitude has been replaced by a sense of urgency and purpose. Arriving back in the US two weeks ago, I was immediately struck by the bustle of activity surrounding the push for emergency preparedness. Here in California, everyone seems to be assembling a grab-n-go “bug-out” bag, signing up to get emergency alerts on their phone, and taking CPR and CERT (Community Emergency Response Team) training. Last year’s record-breaking wildfires galvanized the residents of the Golden State. Whatever happens, we are determined not to be sitting ducks. When I spoke with county Emergency Services Manager Chris Reilly, he quoted the local mantra about impending disaster: “It’s not a matter of if, it’s a matter of when.” Rescue workers help a woman trapped by mudslides in Carpinteria, California, January 2018. Photo by Kenneth Song / Reuters As you can imagine, enterprising survivalists are coming out of the woodwork. In their view, civilization is one wildfire away from total collapse, and our survival will soon depend on whether we can chip stones into spearheads and trap small animals using twigs and vines. If that turns out to be the case, I am totally screwed. Obviously I should have paid more attention during the Outdoor Skills class in Girl Scouts. For serious doomsday enthusiasts, the internet is rife with courses like Hammer Stryke’s Small Unit Survival Tactics. “We will overnight in the forest. Bring: Ruck, backpack or daypack, canteen, and what you would expect to have on a bugging out the back door because the Zombies are coming in the front door situation. Firearms are optional if you have them and are trained.” Yikes! (Note to self: check course date, avoid the woods that night!) Amateurs running around in the woods at night with guns. Yes, that doesn't sound at all worrying... Photo by Wolfgang Kumm / picture-alliance / dpa When it comes to being prepared I am all in, but I’m opting for a less physically demanding approach that includes talking with government officials, community organizers, friends, neighbors, and savvy bartenders. I’m trying to get a realistic idea of what’s likely to happen (I’ve already eliminated zombies from the short list) and figure out how I might be useful during the run-up. Here’s what I’ve learned: The science is clear. We are definitely looking at more frequent and severe natural disasters, followed by increasing social turmoil. Things will get messy. But I’m guessing we’re a long way from having to bivouac in the woods with a backpack and optional firearms. In fact, there are plenty of reasons to be optimistic. For a start, people a lot smarter than I am are pouring enormous amounts of time, money, and creativity into finding solutions. NASA scientist Amaya Davis gives a talk organized by my group, ClimateRecovery.org, in Seville, Spain, January 2019. Just before departing Seville, I organized a public talk there featuring NASA scientist Amaya Davis. She mentioned projects currently on the drawing board, including solar radiation management, involving giant reflectors in space deflecting the sun’s heat; aerosol injections in the stratosphere, which would reduce warming but has the pesky side effect of creating acid rain; and techniques to remove CO2 from the atmosphere. “Giant reflectors in outer space?” I said to Amaya afterwards. “Aerosol injections? Sounds like science fiction!” “Oh, the ideas get a lot wilder than that,” she said. Unfortunately we were interrupted before we could continue this fascinating conversation, but articles such as Crazy Ideas for Plan B: Seven Ways to Engineer the Climate describe proposals such as mass fertilization of the oceans with microscopic plants called phytoplankton that “gobble up CO2 and drag it to the bottom of the ocean when they die.” Sound loony? So did Aristotle’s insistence that the Earth is round, Galileo’s belief the Earth revolves around the sun, and Pasteur’s theory that germs spread disease. Think twice before scoffing at “mad” scientists! Many of these projects are being funded privately; it seems the smart money isn’t waiting around for the federal government to step up and take charge. Local community groups and officials are working to reduce waste, control carbon emissions, and beef up emergency-response infrastructure. But as I learned in Ohio, during a major disaster, citizens can’t count on the cavalry to ride to the rescue, especially during the first 72 hours. Clearly my neighbors know that, too. They are reaching out to one another, meeting in church basements, community centers, and living rooms, figuring out ways that we can help each other if — when — we need it most. I grew up on stories about World War II and often wondered how it felt to be filled with the sense of common purpose that drove the war effort. One of the original “Rosie the Riveters,” Betty Soskin, told me about workers in the Richmond, California shipyards, divided by racial friction. “Because they’re all living under the threat of fascist world domination, there’s no time to take on a broken social system,” she said. “No time to do anything except take on the mission of their leader, which is pure and simple: build ships faster than the enemy can sink ‘em. And together they completed 747 ships in three years and eight months. They helped to turn the course of the war around by out-producing the enemy. And in the process, they accelerated the rate of social change, so that to this day it still radiates out of the Bay Area into the rest of the nation.” Betty Soskin, California's oldest park ranger, talks about how global threats can accelerate the pace of social change. Today, the Bay Area finds itself on the front lines in the struggle to cope with our changing environment. Our vast forests are going up in flames, scientists predict the mother of all earthquakes within 30 years, and rising sea levels are deeply worrying for everyone near the coast, especially my flood-prone little town. Can we, like those shipbuilders, pull off another miracle of unity and strength, one that radiates out to the rest of the nation, maybe the world? As a die-hard optimist, I say we can. And I’m counting on all of you to help prove I’m right. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|