|

“Hey, this is the Dragonpit!” exclaimed my sister Kate. “The actual Dragonpit from Game of Thrones.” “Yep,” I said. “Although sadly, it doesn’t have any actual dragons in it at this time.” We were in the ancient Roman city of Italica, just six miles northwest of Seville, visiting the remains of the massive amphitheater built to enable 25,000 bloodthirsty spectators to watch gladiators fight to the death. In much the same spirit, 10 million Game of Thrones fans found themselves riveted to other epic clashes filmed on this spot, including this meeting between the psychopathic queen Cersei Lannister and Daenerys “Mother of Dragons” Targaryen, a woman who really knew how to make an entrance. Italica was a great place to visit even before it was discovered by Hollywood location scouts; I’ve been taking visitors there for 15 years and they always love it. The city, founded in 206 BC to house veterans returning victorious from the battlefield, was home to two emperors and thrived under their patronage; at one point it was the second largest city in the Roman Empire. Today the most important artifacts have been safely removed to the Archeological Museum of Seville, but the 128-acre site is still impressive, with paved streets, gorgeous mosaic floors, and of course, the amphitheater. Or as we know it today, the Dragonpit. “There’s not a single sign or flyer about it being the Dragonpit,” Kate marveled, looking around at the ancient stone walls. “No mention anywhere of Game of Thrones.” Having grown up in California, in a family with several Hollywood actors, we both found it astonishing that nobody had thought to capitalize on the fame of the site. But that’s Seville for you; it likes to act cool and nonchalant whenever Hollywood comes to town. During the filming, a friend was walking through my neighborhood when a long, black car pulled up at the curb and she saw Nikolaj Coster-Waldau (Jamie Lannister) and Gwendoline Christie (Brienne of Tarth) emerge and go into Bar Alfalfa, one of my favorite places to grab a coffee. Did anyone take a picture and post it on the wall? Get them to sign menus or napkins? Apparently not. I have been in this café dozens of times since then, including yesterday with my sister and brother-in-law, and there’s nothing to show the actors were ever there. To round out my sister’s impromptu Game of Thrones tour, we went to Seville’s Royal Alcázar. This spectacular palace was built in the fourteenth century by Pedro the Cruel on the ruins of an old Moorish fort where, it’s said, they used the skulls of their enemies for flower pots. Somebody persuaded Pedro to get rid of the skulls, and I think we can all agree that was a good call. Today, the palace is home to the Spanish royal family when they’re in town and a favorite with visitors from around the world. It includes a breathtaking mix of every architectural style in vogue for the past 700 years. My favorite part? The elaborate pleasure garden, which Game of Thrones fans will recognize as the Water Gardens of Dorn. Of course, GoT location scouts weren’t the first to discover that Seville is always ready for a close-up. Generations of filmmakers have fallen in love the grand sweeping arc of the Plaza de España, a 1928 architectural fantasy with turrets, colonnades, and a moat crossed by a series of lovely arching bridges. In 1968 it stood in for the Cairo British officers’ club in the scene from Lawrence of Arabia where Peter O’Toole scandalizes everyone by storming in dressed as a Bedouin and demanding a lemonade. A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, the Plaza de España took on the role of a city on Planet Naboo for the underwhelming 2002 prequel Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones. The backdrop is gorgeous; the actors are young and handsome; the dialog is excruciatingly wooden. Don’t feel obliged to watch all of this short clip; fast forward to the end where the setting morphs into the real Plaza de España, which is genuinely worth a look. Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones was far from the worst film ever made in Seville; I personally award that distinction to Knight and Day, shot here in 2009. When word got out that Tom Cruise and Cameron Diez were coming to town to film a romantic action movie, and that they were calling for people to sign up as extras, half the city went down to the casting office to see if they could get in on the fun. Sadly, Rich and I were turned away because at that time our residency visas didn’t allow us to take paying jobs in Spain. Many of our friends did get hired, and Rich and I suffered through one hour and forty-nine minutes of idiotic dialog and hammy acting to see spectacular shots of Seville with nanosecond-long glimpses of our amigos in the background. I happened to walk by while stuntmen were filming this scene, so it’s one of my — well, not favorites, that would be going too far, but I guess I can say it’s the part of the movie I dislike the least. Now, I know what you’re thinking: “Hey, I didn’t realize Seville has the running of the bulls!” We don’t. That takes place elsewhere, most notably in Pamplona, as immortalized by Ernest Hemmingway in The Sun Also Rises. Evidently the filmmakers figured nobody would know — or care — about the inaccuracy, and perhaps American audiences didn't, but here in Seville everyone roared with derisive laughter. As luck would have it, Rich and I did have one brush with stardom while Knight and Day was being filmed. One evening, as we were having tapas in the (now defunct) Aguador de Sevilla, Cameron Diaz came in with some friends and asked for a table. The manager glanced around, shrugged, and informed her they were full. She walked out looking stunned; I don’t imagine that has happened to her since she got her big break in The Mask in 1994. Did the manager recognize her? Probably. The film was the talk of the town that spring, and quite likely some of his friends, family, and/or customers were working as extras. But as I said, Seville likes to play it cool. The city was founded by Hercules, sent two emperors to Rome, gave Christopher Columbus his send-off to the Americas and his final resting place in the cathedral. It takes a lot to impress a Sevillano. Now, if someone showed up on an actual dragon, then the city just might sit up and take notice. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY

3 Comments

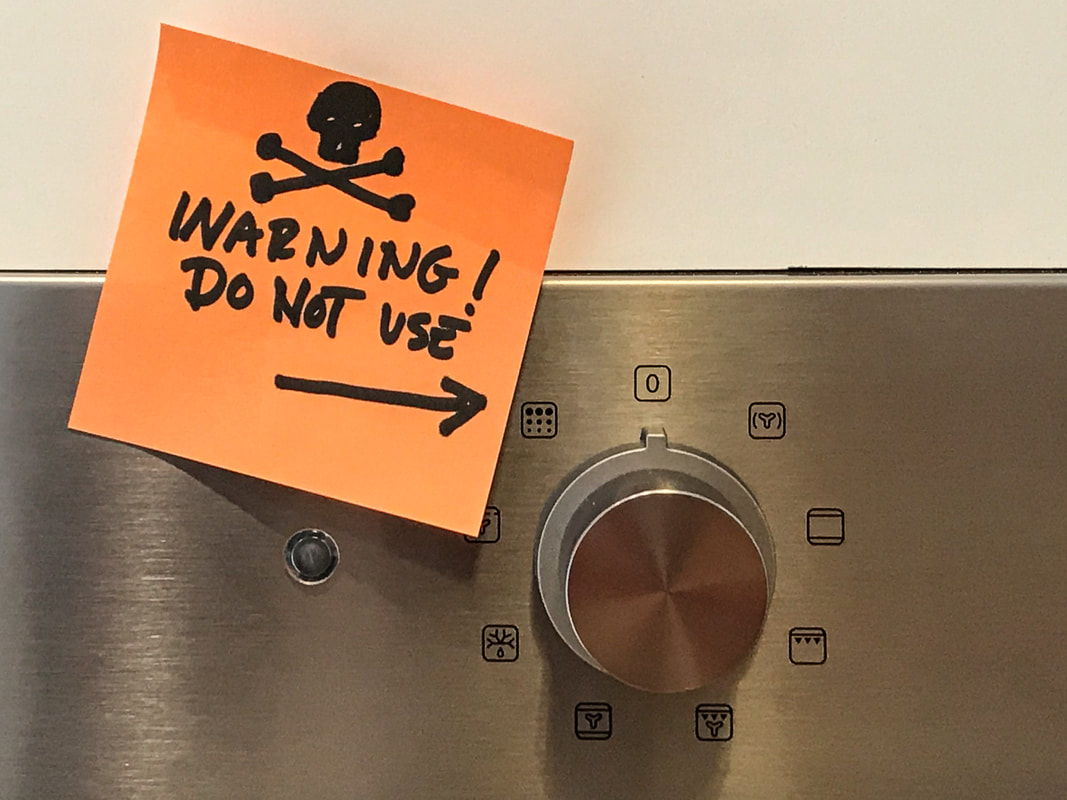

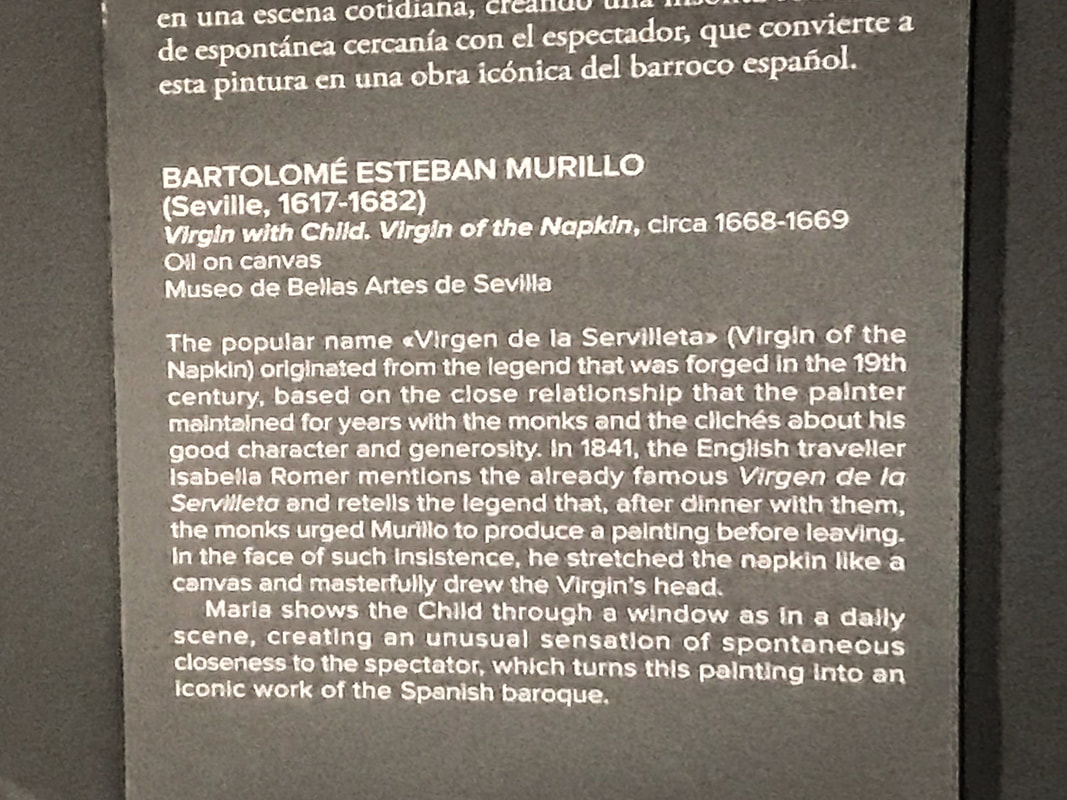

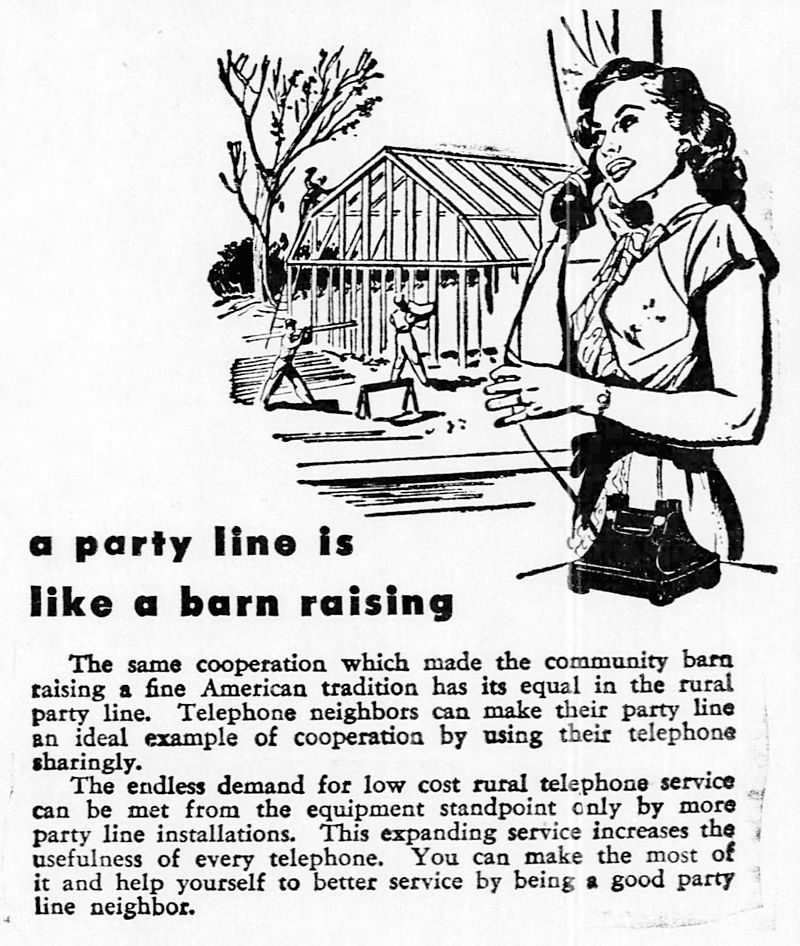

“And whatever you do,” said the technico who had just installed my gleaming new self-cleaning oven, “don’t use the self-cleaning feature.” “What? Why?” “It raises the oven temperature to 6000 degrees, to convert grease to ash. I had to really jam the stove under your countertop — which is narrower than standard, by the way — so the plug is right up against the oven. You use the self-cleaning feature, you melt the plug. And then…” He didn’t need to go on. My fantasies of maintaining a spotless oven had just gone up in smoke. I started to laugh because it was such a supremely Spanish moment. In making an effort to upgrade, I’d moved two steps forward (a slightly roomier and much less temperamental oven) and taken one giant leap toward burning down the entire apartment building. In its own weird way, it was rather comforting. Seville has changed so much lately, it was good to know the city hadn’t lost its quirky, unpredictable character, its innate ability to infuse even the most ordinary act with mystery and high drama. I’ll admit that I’ve been experiencing a bit of post-trip culture-lag following my five month Mediterranean Food Tour. Returning to a city you love after a long absence is always difficult; the tiny, incremental changes that took place over time hit you all at once. Just when you long to wrap a familiar place around you like a favorite old coat, it feels alien, awkward, and ill-fitting, as if it had shrunk several sizes, grown an extra sleeve, and lost all its buttons. Speaking of ill-fitting clothes, the city just lost one of its emblematic old shops that had provided generations of Sevillanos with cheap house dresses and men’s shirts. It was called El Mato, and the clothes were so inexpensive it gave rise to the saying, “Tan barato como El Mato,” as cheap as El Mato. This would crop up in exchanges like, “How was your hotel in Morocco?” “Not very nice, but I will say it was as cheap as El Mato.” Rich once bought a short-sleeved collared shirt there, and it was actually fairly decent except that the short sleeves were extremely short, no doubt to save on fabric costs. He wore it for years, and I assured him it didn’t look odd at all. I’m sorry to report that El Mato closed its doors last month and the site is now a bright, modern Mr. Cake bakery. It’s a bit sad to lose an old-fashioned shop like El Mato (and the dozens of others that have disappeared lately), but the real challenge is adapting to the tourist boom that’s rocking the city. Arriving back in late September, I found crowds jamming the downtown streets like something out of a dystopian movie (the teaming hoards in Soylent Green and the zombie stampede in World War Z come to mind). From 2014 to 2018 (the year Lonely Planet declared Seville the world’s top destination) tourism rose almost 35%, and when the 2019 statistics come out, I’m guessing it will prove to be another record-breaking year. I’ve heard 32 hotels are being built in the city, and new restaurants seem to pop up every day. Some are wonderful, but all too many are cookie-cutter corporate chains offering burgers, pizza, and chicken Caesar salads. Bars now sell drinks with umbrellas and pineapple in them, to underscore the theme: you are on vacation does it really matter where? “It’s all your fault,” a friend told me. “If you’d just stop saying nice things about the city on your blog, we might have a chance of stemming the tide.” I don’t actually believe that I’m the prime mover here, but I felt I should meet him halfway. “How about I start a rumor that the Great Plague is back?” In the middle of the seventeenth century, this grisly disease claimed the lives of a quarter of the population the city, when the national average was 5%. Why? Because the Sevillanos of the day — those old scofflaws — ignored, evaded, and refused to enforce the efforts to maintain quarantine. “The Great Plague?” he said. “Yes, that should do nicely.” I promised to mention it on my blog at the earliest opportunity, and now I have. Feel free to help me spread the rumor far and wide. But for the most part, I’m trying to adapt to the new reality, not fight it. As Rich keeps pointing out, all cities change constantly; it’s what keeps them vital and alive. I’ve occasionally visited towns — Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina, for instance, or Český Krumlov in the Czech Republic — where they’ve worked so hard to preserve the town as it was during a single moment in its history that the place has become a theme park, a plasticized, Disneyland version of itself. I strongly doubt that will be Seville’s fate. This city is too quirky and unruly ever to line up behind any single idea, even one with such obvious benefits as fighting the Great Plague. Twenty years ago, I was gobsmacked to discover that the many city maps of Seville were all drawn differently — some, for instance, enlarged alleys that were useful shortcuts, while others fudged the angles of streets to suggest they all converged on an important landmark. I finally realized each cartographer was being helpful, drawing attention to navigational elements that might be overlooked on a more accurate rendering. That attitude certainly hasn’t changed. Does a self-cleaning oven really heat up to 6000 degrees? Of course not. The maximum is 471 Celsius (880 Fharenheit). Our technico was merely exercising his God-given right to convey information with sufficient drama to ensure we’d be too terrified ever to consider using the self-cleaning feature. He wasn’t just installing an oven, he was saving our lives. And he was serving as a timely reminder that in the midst of constant upheaval, Seville’s kind heart and quirky spirit remain as strong as ever. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY “And this is the Virgin of the Napkin.” My Spanish friends beamed fondly at the painting, hung in its own exquisitely lit niche in Seville’s Museo de Bellas Artes (Fine Arts Museum). Sometimes both talking at once, each one jumping in with colorful details, my friends explained that the famous seventeenth century artist Bartolomé Esteban Murillo had painted this incredible work on the back of a napkin one night after dinner. He'd been dining with some monks here in the city, and afterwards they’d asked him to paint a little something for them as a memento of the evening. Murillo, who apparently had brought along his painting gear, picked up a napkin (presumably not the one he’d been wiping his lips with during dinner), stretched it like a canvas, and began this work. “Increíble!” I exclaimed, as I was clearly meant to do. “Casi un milagro.” Incredible. Practically a miracle. My friends glowed with pride and pleasure. That was fifteen years ago. And while I naturally had my doubts about this story — for a start, even a painter as gifted as Murillo couldn’t dash off a work that detailed in a single evening — it was still a shock to arrive at the museum ten days ago and discover that the painting had been thoroughly debunked. Yes, the work was indeed painted by Murillo, but the legend involving napkins and monks originated in the nineteenth century and soon went viral thanks to British travel writer Isabel Romer, who loved digging up colorful, offbeat stories for her readers. (A woman after my own heart.) The painting has been moved to a lesser position next to some of Murillo’s larger works; clearly it’s now a mere footnote in the great man’s story. Having a cherished legend debunked is one thing; it’s considerably more disconcerting to discover wild inaccuracies in our very concept of what our planet looks like. Remember the world map that hung on the wall in your grammar school classroom? It’s all wrong. That image of world geography got its start in 1579, when Gerardus Mercator cleverly represented the world as a grid that navigators could follow using straight compass lines, eliminating the need for constant, tricky course corrections. Fast forward nearly 400 years to when my husband was in the navy, and the Mercator projection was still the gold standard, used on his ship to navigate the route between Norfolk, Virginia and Gibraltar. The Mercador projection may be great for sailors, but it has the unfortunate side effect of distorting the size of land masses, enlarging those further from the equator until Greenland (836,330 square miles) looks bigger than South America (6,890,000 square miles) or even Africa (11,730,000 square miles). Today there’s growing support for the Gall-Peters projection, which attempts to correct the geographic distortion of Mercator’s approach. Naturally, this new work is surrounded by its own controversies, with some cartographers sneering at James Gall (a 19th century clergyman) and Arno Peters (a 20th century German filmmaker) as unqualified hacks. The Controversy section on the Wikipedia page reads like a Facebook rant. Nevertheless, the Gall-Peters projection is gaining traction; it’s now being promoted by UNESCO and has been adopted by a growing number of British and American schools, where it’s viewed as a more accurate and equitable representation of the planet’s geography. Ours is a world full of controversy and dissension, and just about the only thing we can all agree on is that we live in an age of disinformation. Sometimes it helps to remind ourselves that there’s nothing new about distorting information and disseminating it far and wide. Just this morning at breakfast Rich was talking about the party line telephones of his childhood. For younger readers, this was back in the dark ages before everyone had their own phone, and houses in a neighborhood would often save money by sharing a single land line. When the phone rang, everyone would run pick up, and when it was for you, the neighbors were supposed to hang up — but of course they secretly stayed on the line, listened in, and then proceeded to share all your news and gossip with everyone within their orbit. Rich calls it “the forerunner of Facebook.” With disinformation ramping up online, I find it comforting to spend time in countries that haven’t (yet) been overwhelmed with bot-fueled globalized thought manipulation. One night in May, I was on the Greek island of Ikaria, famous for the remarkable health and longevity of its residents. An election was coming up, and a meeting had been called in the village of Evdilos; chairs were set out under the trees near the wharf, and what appeared to be the entire population of the village gathered at twilight to sit and listen to the candidates. Here, politics was still a face-to-face business that didn’t rely on sound bites and social media. In its own small way, it was breathtaking. It’s easy to feel helpless in the face of globalization and mass disinformation. But standing at the back of that crowd on Ikaria, I was reminded that we still live in human communities. It is our nature to talk among ourselves, sharing information, weighing facts, exploring ideas, arguing, attempting to winkle out the truth of a subject. We do it with friends and family at home and, if we’re lucky, with those we meet during our journeys. “The antidote to misinformation is exchange: to send truth-tellers around the world," said former U.S. ambassador Jeffrey Bleich. “Truth-tellers—mathematicians, scientists, musicians—return from places and can tell people objectively what they saw and experienced and learned, and restore critical and analytical minds.” Being a truth-teller is important work, and every traveler can do it. When we have the good fortune to spend time talking with people of other cultures, we bring home fresh perspective not only on their culture but our own. “Travel,” says globetrotting author Rick Steves, “challenges truths we were raised thinking were self-evident and God-given.” And that’s a wonderful thing. Because it shows we don’t have to live in a “post-truth” world, as some in the media would have us believe. Yes, there are plenty of people around who are careless, callous, and conniving with the truth. But there are still millions of us who persist in caring about the nature of reality, verifiable facts, and the precise shape of our world. And that’s truth worth knowing. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY |

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|