Latvia, as even the Latvians will admit, is not precisely the center of the universe. It’s the middle Baltic State, tucked between Estonia and Lithuania, and until this year, I would have been hard pressed to pinpoint it on a map of the world — or even, to be honest, a map of the Baltics. The capital, Riga, is a hot destination for Russian bachelor parties but hosts few American, British, or Spanish visitors. Yet in just a few days here, we’ve connected with various friends, some from Seville and some we’d recently met in Estonia, all of whom happened to be passing through Riga. Apparently, others do not share my difficulty in locating Latvia on a map. Riga may be gaining popularity, but there is nothing mainstream about it. Oh sure, there’s a charming Old Town, a UNESCO World Heritage site with splendid Art Nouveau buildings, noteworthy art museums, even a TGI Friday’s. But scratch Riga’s conventional surface, and you’ll find much edgier stuff. We started with the Pauls Stradiņš Museum of Medical History. Displays cover such health care high points as pre-historic skull drilling, nuns nursing victims of the black plague, straightjackets with shackles, medieval surgical implements, and an iron lung. For an extra 43 cents we were allowed into the basement for the special gastroenterology exhibit featuring large, colorful images taken during actual endoscopies and colonoscopies. How fun is that? The exhibit’s title (I am not making this up) was “Where the Sun Never Shines.” But by far the grisliest object we saw was the stuffed remains of the two-headed dog, the result of an experiment in which Soviet surgeon Vladamir Demikhov succeeded in joining two animals together. He advanced science considerably, paving the way for human heart transplants and earning acclaim in the international medical community. Dog lovers, however, tend not to be fans of his work. Feeling the need for a cheerier setting, Rich and I headed to the Sun Museum, which turned out to be a random assortment of solar-themed art owned by a local woman named Iveta Gražule. It was like visiting that eccentric relative who collects umbrella cover sleeves or UFO memorabilia; you admire the perseverance but keep wondering why on earth anyone would do it. We were in and out in ten minutes. I had higher hopes for the World of Hat, another private-collection-turned-museum, and one that we tracked down with great difficulty in an obscure courtyard. It was meant to be visiting hours, but no one answered the bell so we’ll never know what we missed. We then spent time admiring Riga’s giant snail, a relic of a 2014 campaign in which large plastic snails were placed on city sidewalks in hopes of stimulating interest in building a contemporary art museum. It failed utterly to achieve that goal, but residents had a marvellous time pushing the snails up and down the sidewalks and taking selfies with them. Another famously unsuccessful effort was Riga’s Hospitalis restaurant. Spaces were decorated like hospital suites, waitresses were dressed as nurses, and meals served on metal trays were eaten with surgical implements. If you paid extra and signed the necessary waivers, they would put you in a straightjacket and feed you. I can only assume this concept dining experience was a joint project with the Pauls Stradiņš Museum of Medical Horrors (I’m sorry, I mean History). Incredibly, Hospitalis is no longer in operation. Far scarier and all too real is the Corner House, the infamous basement in which the KGB conducted interrogations, now opened as a museum. As the old joke goes, “The Corner House has the best view in Riga; from there you can see Siberia.” But why simply observe relics from the past when you can have the full immersion experience in a Soviet prison hotel? A few hours from Riga, the former military prison Karosta offers tours that include being thrown in cells, yelled at by guards, and dragged outside to perform exercises. If you pay extra, you get to wear a prison uniform, spend the night on a wooden slab with a thin blanket, and suffer insults, interrogations, and punishments. “Not all of the guards are completely fluent in English,” one website notes. “American visitors are often surprised by the amount of abuse they receive.” The prison is, of course, said to be haunted. “I take my students there,” a schoolteacher told me. “How old are they?” I asked, aghast, imagining first graders handcuffed to radiators in an excess of verisimilitude. “Teenagers. They love it.” She explained that locals born after the Soviet era are eager to discover how they would handle themselves under hardships like those suffered by their parents and grandparents. Am I ready for immersion in the Soviet experience? “Don’t even think about it,” Rich told me. “I don’t care about the rest of it, but I am not spending the night on a wooden slab.” “Don’t be silly,” I said. “You’d mouth off to a guard, and they’d have you out in the yard doing pushups till dawn.” The Karosta prison hotel may not work for us, but if you’re looking for a truly unique place to rendezvous with friends, consider Latvia. Conveniently located between Estonia and Lithuania, this little country offers big opportunities to make memories that will last a lifetime. THE PLAN: 3 MONTHS ON TRAINS & FERRIES WITH AN OPEN ITINERARY & SMALL SUITCASES. Distance covered so far: 2648 km / 1645 miles. Highlights have included zany Amsterdam, the German city of Lübeck on the edge of the Baltic Sea, the Stockholm disaster, the new foodie mecca of Helsinki, Finland, futuristic Estonia, and a surprisingly kookie Riga, Latvia. We're now in Kuldīga, a small town in the Latvian countryside. To follow our adventures as they unfold, subscribe to this blog, like my Facebook page, and keep checking the map of our journey.

13 Comments

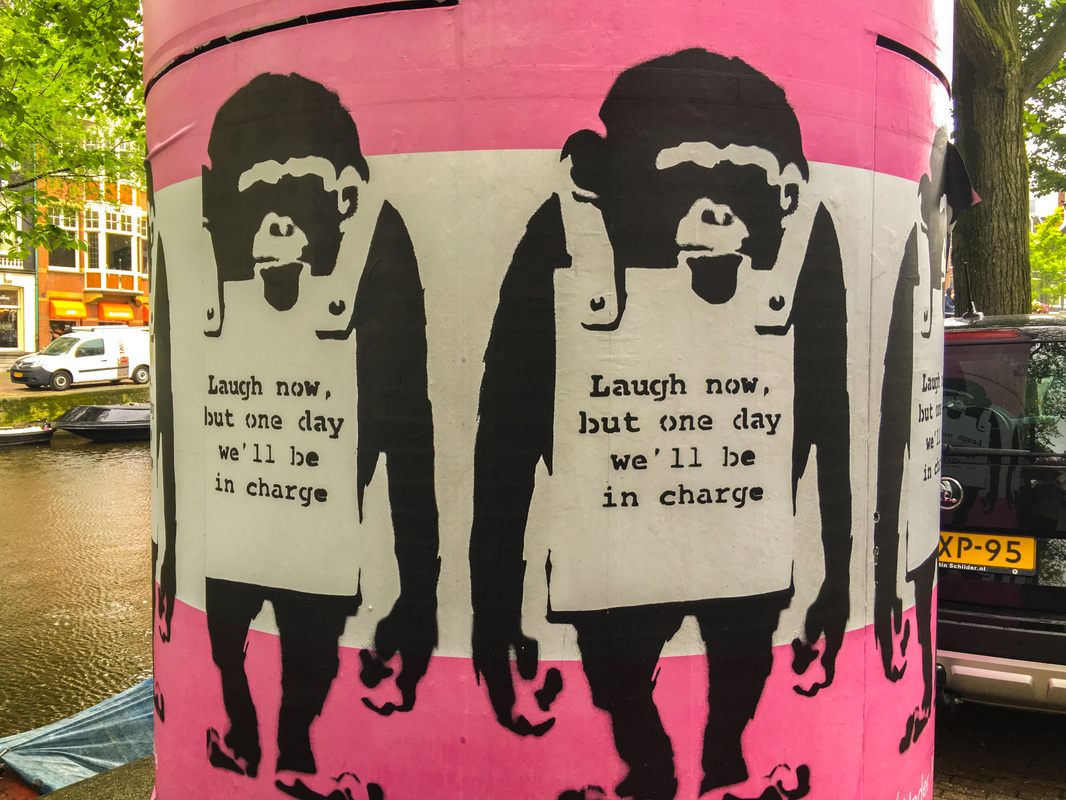

“I remember driving around with half a sheep in the back of the car,” Martin said. “Because in those days, when you went visiting, you always brought your own food.” We were in Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, a small country perched precariously between Russia and the Baltic Sea. As you can imagine, Estonia has been invaded by every major seafaring nation around and spent most of the twentieth century under the successive domination of the Russian Empire, Nazi Germany, and the USSR. The Soviet half century was particularly dismal; if you managed to survive the mass deportations to Siberia (Estonia lost 25% of its population by the end of WWII), you had little food or money, and lived with rampant, completely justified paranoia. “They kept telling us how great everything was,” said Kay-Krister, with the kind of deadpan irony often found in former Soviet citizens, who have a knack for conveying an eye roll and a mental shrug without any perceptible change of tone or expression. “They were schizophrenic times.” Kay-Krister was escorting us through the infamous KGB headquarters on the Hotel Viru’s twenty-third floor, a penthouse level the Soviets denied even existed. She showed us surveillance devices that seemed like props from a Cold-War era James Bond movie: the microphone hidden in the bread plate, the camera that shot through a peephole, massive reel-to-reel tape recorders. How closely were the KGB listening? “One visitor," she told us, "said to his wife, ‘Look, they didn’t even give us toilet paper!’ Two minutes later came a knock on the door. They opened it and someone was standing there, holding out a roll of toilet paper.” So how did the Estonians finally win their freedom from the superpower next door? They called it the Singing Revolution. The Soviets had outlawed Estonia’s patriotic songs, but by 1987, with the USSR struggling to hold itself together, people began to sing the forbidden tunes at ever-larger public gatherings. As one Estonian put it, “If twenty thousand people start to sing one song, then you can’t shut them up, it’s just not possible.” In 1988, nearly 300,000 people — more than a quarter of the population — came together at the Song of Estonia festival, waving flags they’d kept hidden for generations. And on that day, Estonia’s political leaders began talking seriously and publicly about the road to freedom. There was more to it than singing and talking, of course, and tanks were eventually involved. But Estonia prevailed, winning its freedom in 1991. “We were lucky to have good leaders,” Martin’s wife, Erge, told me. The new government, she explained, invested wisely in education. Literacy is now 100%. Every Estonian is taught computer programming in grammar school and has access to a free university education and free Wi-Fi. With the universal Estonian ID card, virtually all banking, voting, taxpaying, and medical record-keeping happens online. Estonia is the first country offering the opportunity to become an e-resident, which lets you set up and administer an Estonian business remotely. Skype got its start here, and today this little country has the highest number of startups in Europe. Government support for startups includes favorable taxes, streamlined paperwork, and good advice. “Do you …” I had never asked this one before and could hardly get the words out of my mouth, the concept was so foreign to me. “Do you trust your political leaders?” “Yes,” Erge said, as if it was the most natural thing in the world. “I think they’re moving in the right direction. They are honest. We don’t have a lot of corruption.” This staggering statement piggybacked on another stunner I’d heard earlier that day. We were standing in front of the Parliament building when our guide, Heli, asked, “What don’t you see here?” We looked around blankly. “There are no gates, no guards. Sometimes when I am giving this tour we see the prime minister, walking out of the building, alone. He just waves.” She laughed at our expressions. “This is an open society.”  Leib's signature black bread, beautifully paired with a crisp Italian orange wine Leib's signature black bread, beautifully paired with a crisp Italian orange wine We were in Tallinn’s Old Town, where the cobblestone streets were bustling with locals and visitors strolling past medieval buildings, many housing inviting shops and restaurants. There is plenty to buy, and you no longer need to bring along half a sheep as a hostess gift. But locals have not forgotten their roots. One of the hottest new eateries is Lieb, which means black bread, the staple of Estonian cuisine through good times and bad. Kristjan, Leib’s co-owner and sommelier, loves international recipes and imported wines, but makes sure the food is solidly grounded in local ingredients. “Here in Estonia,” he told me, “we do not have the richest soil. It is not the best climate. Our vegetables have to suffer a bit to grow. And that is how you get the best flavor.” Estonia is, like its vegetables, no stranger to hardship. But in just 25 years of freedom — the longest stretch of independence since the Danes invaded in 1206 — this little country has earned a place at the table where our technological future is being created. Kind of makes you wonder what other surprises Estonians have in store for us in the years ahead. We have been on the road a month and have covered 2296 km / 1427 miles. Highlights have included zany Amsterdam, the German city of Lübeck on the edge of the Baltic Sea, the Stockholm disaster, and the new foodie mecca of Helsinki, Finland. We're now in the Baltic State of Estonia; after a week in the capital, Tallinn, we've just headed onward to the university town of Tartu. To follow our adventures as they unfold, subscribe to this blog, like my Facebook page, and find our current location on the map. The Finnish don’t like to make a fuss, especially about themselves. In fact, they are so self-deprecating they make English reserve look positively brash by comparison. Q: How can you tell the difference between a Finnish introvert and a Finnish extrovert? A: When he’s talking to you, a Finnish introvert looks at his feet. A Finnish extrovert looks at yours. But that doesn’t mean people are pushovers. “The word that best defines the Finnish is ‘sisu,’” explained Heather, our guide on the excellent Heather's Helsinki "Fork in Hand" food tour. “There’s no exact translation, but it means something like the willingness to persevere when anyone else would have given up.” Frankly, I can see how people would be tempted to give up on Finland, if only because of the weather. Up north, in the Lapland region where Father Christmas is said to reside, thermometer readings can plummet to 50 below zero, there’s snow from October to April, and for two months the sun never peeks over the horizon. Helsinki isn’t quite that bad, with freezing temperatures for “only” five months a year. “Around here,” Heather told me, “people say, ‘There is no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing choices.’” Yikes! Now that’s sisu. As Heather led us through downtown Helsinki’s charming markets, shops, and parks, past lovely buildings in styles ranging from neoclassical to Art Nouveau to Byzantine-Russian, I began to be seriously impressed. Helsinki is a friendly, walkable city where people spend a great deal of time sitting around drinking coffee (12 kilos per person per year, more than any other nation) and trying to figure out how to make life better in small, unassuming ways. For instance, somebody had the bright idea of covering every playing field in the city with gravel instead of grass, so they could be flooded with water, easily and cheaply creating free public ice skating rinks every winter. Someone else suggested creating a 20-minute meal station at Stockman’s supermarket; every few days there’s a new, quick-prep menu, with all the recipes and ingredients collected handily in one grab-and-go place. And we all have to thank whoever dreamed up the city’s Restaurant Day, which launched a lot of culinary careers — and the concept of the pop-up restaurant. One young food entrepreneur who got her start on Restaurant Day is Elizabeth, an American expat who wondered if her adopted city would have a taste for treats from her homeland. Today she’s running Blondie Bakes in Vanha Kauppahalli, the Old Market Hall on Helsinki’s waterfront. Built in 1889, this local landmark offers foreign delicacies including Elizabeth’s sweets, French cheeses, and Spanish ham, along with such traditional local favourites as reindeer, horse, elk, bear, nettle soup, and sea buckthorn jam. During our stay in Helsinki, Rich and I ate in the Old Market Hall, sidewalk cafés, top rated restaurants, funky bars, and random bakeries that appeared when we needed a caffeine and sugar fix. We were frankly astonished; everything was delicious, even the extremely creative dishes that looked so great we were certain they’d disappoint — but they never did. We voted Helsinki the best food town of this trip, possibly of our travel careers. But Helsinki isn’t only about the food. Artwork is scattered about the landscape thanks to the Helsinki Art Museum, which has placed half of its 9000-piece collection in parks, streets, offices, health centers, schools, and libraries “to brighten everyone’s day.” If your day needs even more good cheer, you can always go gaze at the outrageously colorful textiles at one the Marimekko stores, which were launched in Finland in 1951 “to bring joy to everyday life.” Another Finnish product that is now known worldwide is Fiskars. In 1967 the company revolutionized the look of scissors by adding bright orange plastic handles — the result, the company says modestly, of a thrifty move to use up leftover orange plastic from their juicer product line. Another highly popular Finnish product is, of course, beer. The beloved golden beverage has been brewed in Helsinki for nearly 500 years, since the days when the town had just two thousand residents and 39 beer merchants. Heather took us to one of the hot new microbreweries, Bryggeri, where we sampled four freshly made beers and Bryggeriwurst, a sausage created specifically to compliment their beer. Heather introduced us to the brewmaster, Mattias, and we made a fuss and said nice things about his work until he started staring at his feet, and then we let him go.  A customer satisfaction survey at a restaurant in Helsinki's hipster district. A customer satisfaction survey at a restaurant in Helsinki's hipster district. “I get clients,” Heather confided, “who tell me their travel agents advised them to skip Helsinki because there’s nothing to do.” I just don’t get that at all. Rich and I loved the people, the architecture, the shops, the museums, and the fabulous food. Would we go back? As the city’s promotional campaign puts it, “HEL YEAH!” THE TRIP SO FAR. Our three-month train trip began when we landed in Paris on June 28 and immediately hopped on a train to Lille, France. Two days later we visited friends in Amsterdam, then continued by rail to Germany. After a brief stopover in Osnabruck, we arrived in Lübeck, on the edge of the Baltic Sea. After some culinary adventures there, we took a ferry north to Sweden, landing in Malmö and continuing on to Stockholm. After the Stockholm disaster, we moved on to Helsinki, Finland. Tearing ourselves away from Helsinki's great culinary scene, we're currently enjoying the friendly city of Tallinn, capital of Estonia. To follow our adventures as they unfold, subscribe to this blog, like my Facebook page, and find our current location on the map. “We have to get out of here,” I hissed to Rich. “As fast as possible,” he agreed and began chugging his Heineken. “Leave it,” I urged. “Are you kidding? These beers cost nine dollars apiece!” We were standing on the terrace of an upscale Stockholm hotel, surrounded by beautifully groomed people who were talking, laughing, and — as soon as they noticed us — staring and glaring in our direction. Clearly our very presence was sucking all the trendiness out of the occasion. We were at an event organized by InterNations, the expat social network that holds casual gatherings in 390 cities around the world. Rich and I are long-term members of the Seville branch and sign up to attend in other cities when we’re passing through. I’d come to expect a welcoming smile, a sticker with my name and nationality printed on it, and interesting conversations with expats and locals. Now, standing on the overcrowded terrace with music blaring and everyone looking daggers at me, it was all I could do not to drop to my belly and crawl to the elevator. It turned out that in our excitement at discovering that an InterNations event coincided with our visit to Stockholm, we had overlooked one tiny detail: this was not an event for the main group but a young singles night. Hoppsan! (That’s Swedish for oops!) Rich and I guzzled our drinks and fled. As disasters go, I’ve seen far worse. And so, of course, has Stockholm. One of its most spectacular catastrophes of all time was the launch of the warship Vasa in 1627. Back then Sweden was in its stormaktstiden, age of glory, and King Gustavus Adolphus, the Lion of the North, wanted his navy’s new flagship to be the biggest, baddest warship on the high seas. When the Vasa was finished, she measured a massive 69 meters long and 50 meters high. Everyone turned out to watch the gigantic ship embark on her maiden voyage. The Vasa sailed boldly for a grand total of 1300 meters — and then she sank. It seems someone had forgotten to close the gun ports, and when a little squall tipped the top-heavy craft to one side, water rushed in and filled the lower part of the ship. Fifty people and the grandest ship ever built were lost in minutes as the horrified crowd watched from shore. The ship lay on the harbor floor for 333 years, and then in 1961 a salvage project raised the hull, which was surprisingly well-preserved by the brackish water. The ship, still undergoing restoration, is now on display in her very own Vasa Museum and has become one of Stockholm’s most popular tourist attractions. Skimming the Internet for details, I found one writer who seemed thrilled by the Vasa because she was “a real Viking ship!” Well, no. The Vikings (as I learned at Stockholm’s Swedish History Museum) started their legendary raiding and pillaging in 793 and by 1066 were fading from the scene, six centuries before the Vasa disaster. I was disappointed to discover that the Vikings didn’t actually wear horned helmets; those were dreamed up in the 19th century for a theatrical production of a Wagner opera. Worse, I found out Viking funerals didn’t involve placing the dear departed in a longboat and setting it ablaze with a flaming arrow; that was a Hollywood invention. “The Vikings,” said our docent earnestly, “were more farmers than fighters.” What? “But weren’t they famous for their aggressive warfare?” I asked. How many ways had I been wrong about the Vikings? The docent lowered her voice. “They don’t like us to talk about that any more.” Behind her, a movie was showing a vivid reenactment of the infamous Viking raid on Lindisfarne, an island off the coast of what would become Northern England, in 793. Perhaps they were farmers in the off season, but the men in the film made short work of burning down the monastery and killing the monks in violent and gruesome ways. Like the Vasa, the Vikings’ reputation may be subject to ongoing refurbishing, but I, for one, was having a very hard time buying the kinder, gentler image the docent was selling. Whatever the truth is about the Vikings, I found it comforting to know that Rich and I could travel across the Baltic Sea without having to worry about running into any of their raiding parties. After booking our accommodations on the overnight ferry to Finland, Rich glanced at his emails and said, “Hey, there’s an InterNations event in Helsinki while we’re there.” “What kind of event?” I asked suspiciously. “Let’s see … Hmmm, it appears to be a gathering in a sauna.” And that’s when I realized just how much worse our InterNations fiasco could have been. For one ghastly moment, I contemplated what it would have been like coping with that bunch of hostile strangers if the social situation had called for being naked… Now that would be a situation calling for a “Hoppsan!” And a very speedy exit indeed.  Somewhere on the Baltic Sea Somewhere on the Baltic Sea THE TRIP SO FAR. Our three-month train trip began when we landed in Paris on June 28 and immediately hopped on a train to Lille, France. Two days later we visited friends in Amsterdam, then continued by rail to Germany. After a brief stopover in Osnabruck, we arrived in Lübeck, on the edge of the Baltic Sea. After some culinary adventures there, we took a ferry north to Sweden, landing in Malmö and continuing on to Stockholm. After the Stockholm disaster, we moved on to Helsinki, Finland. To follow our adventures as they unfold, subscribe to this blog, like my Facebook page, and find our current location on the Where are we now? page of this website. “Fine, go ahead,” Rich said, shuddering. “Just don’t expect me to eat any of it.” I had to admit, the labskaus didn’t look particularly appetizing. Usually described as a bright purple meat purée colored with beets, mine appeared more of a tired mauve; even the sunny-side-up egg topper couldn’t make it appear anything but drab. However, I refused to be put off by appearances. Medieval German sailors lived on this hearty dish made from minced and boiled salted beef, potatoes, onions, and lard. And here at the Schiffergesellschaft — the ancient hall of the maritime guilds in the port city of Lübeck, Germany — I’d heard they served the best. I fortified myself with a swig of beer and dug in. Imagine corned beef hash made with over-boiled beef, over-mashed potatoes, and loads of lard, seasoned with a dash of beets and a hint of herring. Rich, who loathes beets in any form, could barely look at it, but I have to say, labskaus was far from the worst thing I’ve ever eaten. It was better than Portuguese pig’s ears, for instance, which turned out to be just as rubbery and tasteless as you’d expect. And it didn’t have that peculiar oiliness that makes it so hard for me to swallow the Scots’ beloved haggis. True, labskaus wasn’t quite as good as fried flies, which are as delightfully salty and crunchy — like cocktail peanuts with wings. You don't get that kind of culinary fun with purple boiled beef, but I wouldn’t say it was truly terrible. All the same, I don’t think I’ll be ordering it again soon. OK, ever. In spite of its underwhelming taste and appearance, I rather liked the idea of labskaus. This was the ancient seafaring community’s way of using up odd (possibly questionable) bits of salted meat and root vegetables, creating a filling dish to sustain hungry sailors on voyages throughout the Baltic Sea and beyond. It was as thrifty and practical as the merchants who sent those ships out on ever-longer trading runs. During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Lübeck’s merchants cleverly parlayed a well-placed port into such a prosperous business nexus that they rose to leadership in the Hanseatic League, a vast and powerful trade organization that became the juggernaut of commercial culture in the known world — much like Silicon Valley is today. Since then, Lübeck’s fortunes have waxed and waned, as fortunes so often do. In 1932 the city boldly defied Hitler, refusing to allow him to campaign there; naturally this led to some nasty reprisals later. Toward the end of the war, the Allies bombed Lübeck’s port and devastated the ancient part of the city, but later restorations were so meticulous that the town has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The restorers mercifully managed to refrain from correcting the off-kilter, listing, crooked walls of the original medieval houses, warehouses, and towers in the town center, and combined with the conical black spires rising above the skyline like a gaggle of witch’s hats, this gives the city an endearing resemblance to the illustrations in a child’s book of fairy tales. And that’s what I love about Lübeck. The townspeople never lost sight of the fact that its flaws didn’t diminish the city, they were the very thing that made it marvelous. The charms of imperfection are also part of the appeal of the Lübeck Museum of Theater Puppets, where more than a thousand fantastical figures are displayed in a rabbit warren cobbled together out of half a dozen sixteenth century homes. As you climb up and down spiral staircases and turn unexpected corners, you see plenty of pretty girls and dashing youths, but the most unforgettable characters are the oddballs: grotesque villains, wild-eyed beasts, and scheming crones whose faces are outrageously alive with passion and personality. After wandering, dazzled, through the maze of puppetry exhibits, I said to Rich, “Hungry? I think we owe it to my readers to check out the marzipan.” He responded to this suggestion with considerably more enthusiasm than he’d shown for the labskaus at Schiffergesellschaft. (Go figure.) Legend has it that marzipan, a rich confection of ground almonds and sugar, was invented in Lübeck, possibly as the result of some ancient siege during which all other food supplies were exhausted. Once a delicacy enjoyed by the wealthy, marzipan now enjoys widespread popularity, and local “canditor” Niederegger has a vast downtown emporium on the very spot where marzipan has been sold since the twelfth century. Rated as 100% pure marzipan, Niederegger’s confections are sold worldwide in every shape imaginable, from pigs to dinosaurs to a replica of the city’s famous most landmark, the Holsten Gate. We bought a couple of marzipan hearts covered in dark chocolate and bit into them. Oh. My. God. It was glorious stuff, far better than the American version my parents used to tuck into my Christmas stocking. It was proof that Lübeck’s merchants are still providing, at a reasonable yet profitable price, exactly what the market wants — in this case, something to refresh the palate and chase away the aftertaste of purple puréed beef with hints of beet and herring. WE’RE OFF TO A GOOD START. Our three-month train trip began when we touched down in Paris on June 28 and immediately hopped on a train to Lille, France. Two days later we visited friends in Amsterdam, then continued by rail to Germany. After a brief stopover in Osnabruck, we arrived in Lübeck, on the edge of the Baltic Sea. Since I wrote this post, we’ve taken the ferry north to Sweden, landing in Malmö and continuing on to Stockholm. For more about our continuing adventures, subscribe to this blog and check my Facebook page for updates. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY “Watch your head,” said our Airbnb hostess as Rich and I negotiated the steep steps leading down into our basement apartment. It was like climbing into a hobbit hole. “We had flooding last week with all the rain. I’m sure it will be fine now, but when you go out, be sure to place your suitcases on the sofa. Just in case.” It was the kind of practical yet startling remark that I’ve come to associate with Amsterdam, a city whose deeply embedded common sense and tolerance often lead to a special kind of quirkiness. For instance, I don't know of any other city where you could pay for your drinks with live monkeys. Back in the 17th century, sailors returning from Indonesia and other far-flung outposts of the Dutch Empire often found their thirst outstripped the number of guilders in their pockets, and they began offering their newly acquired pet monkeys as alternative payment. The owner of one establishment said, “Hey, why not?” and soon his tavern was known as In’t Aepjen, which means “In the Monkeys.” According to one account, “Soon the In’t Aepjen was overrun with so many monkeys that customers began to complain of the fleas.” Sincerely hoping they’d solved the flea problem, Rich and I went to check out this unusual watering hole for ourselves. In’t Aepjen is small and charming, with plenty of old, dark wood and countless statues and pictures of monkeys. As we sipped our beers and nibbled on the only bar snack available — large cubes of cheese with mustard for dipping — I tried to imagine how much pandemonium a single monkey could create in there, especially if the room happened to be packed with hard-drinking sailors. And with multiple monkeys romping about? I’m not sure the fleas would be the primary problem. Luckily one of the regulars, Gerard Westerman, volunteered to give all the monkeys a new home in his large garden on the other side of town, and eventually his collection of exotic animals became the city’s Artis Zoo. I don’t know how the monkeys felt about living in Amsterdam, but the humans in this city seem to love it, despite the far-from-ideal weather. Right now, as June slides into July, the gray skies, frequent rain showers, and chilly breezes make it feel distinctly un-summery. I’ve heard that winters can be very cold indeed. But let’s face it, nobody goes to Amsterdam for the climate. My friend Margriet moved to Amsterdam from a Dutch village when she was a small child. “Coming here was so exciting. There was so much freedom. It was a cool city to be in. Back then my father and I had to walk through the red light district to get to the market. In Amsterdam, nobody thought anything about it.” She grinned at my expression. “When you’re young, you’re not easily shocked.” Margriet has lived in Seville (where we met), Paris, and most recently Australia, but she always returns to Amsterdam. Why? “The architecture, for one thing. You can walk over the canals for years and still find it breathtaking.” “Some Australian friends,” she recalls, “told me, ‘Oh yeah, I’ve been to Amsterdam, but I can’t remember a thing about it. Heh, heh.’ They talked of coffee houses and the red light district and that was it. But those places are for the tourists. Nobody from here goes there. Years ago I made a map for visitors that showed the kinds of places locals go: gardens, the cafes where people buy their coffee, the markets, the one-of-a-kind shops. That’s Amsterdam.” “Here people are very much individuals,” she adds. “When I lived in Australia, I couldn’t stand that so many things were being done simply because ‘it’s done.’ In Holland, we have a wide possibility for thought and a culture of strong opinion; we love a good discussion. People criticize, and that’s fine. Everything is discussed.” Living in other countries and working for an international company, she’s found Dutch directness isn’t always welcome and has learned to be diplomatic when necessary. But she’s glad to be living in a place where “freedom of speech is very highly valued and there is a lot of room for new ideas.” Tonight Rich and I will accompany Margriet to watch her Irish fiancé, Patrick, perform in an avant-garde play. They have warned us that it’s edgy stuff, filled with politically incorrect ideas and raw language. Personally, I don’t mind any of that; right now, any evening that doesn’t involve rising floodwaters or being overrun with live, flea-bearing monkeys sounds downright congenial to me. YOU MIGHT ALSO ENJOY But enough about us. What have you been up to lately — travel, staycations, work, play?

|

This blog is a promotion-free zone.

As my regular readers know, I never get free or discounted goods or services for mentioning anything on this blog (or anywhere else). I only write about things I find interesting and/or useful. I'm an American travel writer living in California and Seville, Spain. I travel the world seeking eccentric people, quirky places, and outrageously delicious food so I can have the fun of writing about them here.

My current project is OUT TO LUNCH IN SAN FRANCISCO. Don't miss out! SIGN UP HERE to be notified when I publish new posts. Planning a trip?

Use the search box below to find out about other places I've written about. Winner of the 2023 Firebird Book Award for Travel

#1 Amazon Bestseller in Tourist Destinations, Travel Tips, Gastronomy Essays, and Senior Travel

BLOG ARCHIVES

July 2024

CATEGORIES

All

|